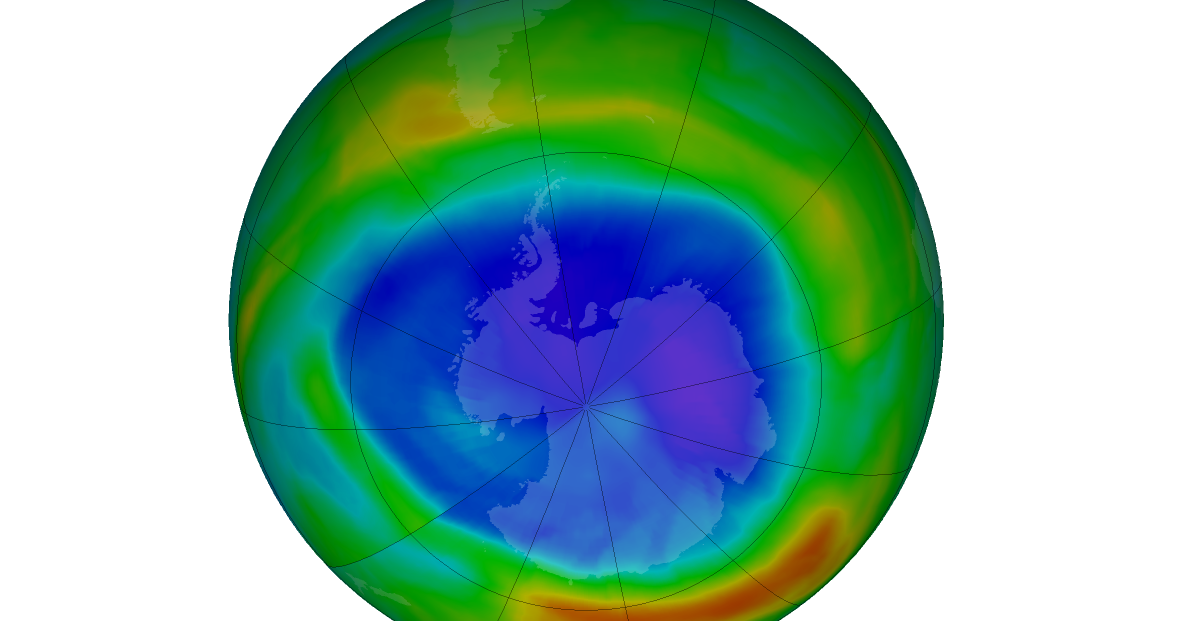

In 1987, the United Nations signed into being the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty an international treaty that targeted chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs, for elimination — substances that threatened to diminish the Earth’s protective ozone layer.

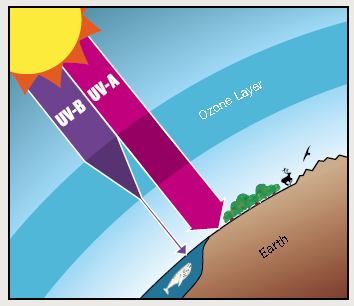

Even in the nearly 35 years since the Montreal Protocol, research shows that the treaty was largely effective in protecting the ozone. The ozone shields the Earth from the sun. Depletion of the ozone would have taken away our protection from the sun and its ultraviolet rays, causing increases in skin cancer and other sun damage. According to atmospheric and climate scientist Dr. Paul Young of Lancaster University in the United Kingdom, the new normal would be the stuff of science fiction.

Supporter Spotlight

“It would be a catastrophic world,” Young said.

And even if the Montreal Protocol hadn’t help save us from incredible harm by the sun, research now indicates that the treaty had other beneficial effects.

Young is the lead author of a recent study published in Nature called “The Montreal Protocol protects the terrestrial carbon sink.” The study shows that in addition to protecting the ozone, the Montreal Protocol also prevented a significant loss of sequestered carbon. Without the treaty, higher levels of carbon dioxide would have remained in the atmosphere.

Across several modeled scenarios, Young and his team concluded that without the Montreal Protocol, there could have been 325-690 billion metric tons of additional carbon not sequestered by the end of this century. This unsequestered carbon could have resulted in 115-235 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This much added carbon dioxide would increase the Earth’s temperature by up to 1 degree Celsius, or about 1.8 degrees Fahrenheit — a seemingly small but catastrophic amount.

Photosynthesis is the process by which plants grow — they take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and use it as fuel. An output of this process is oxygen. Therefore, photosynthesis allows for carbon dioxide to be removed from the atmosphere and become “sequestered” in plant matter, or biomass. Since greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide are a driving contributor to climate change, carbon sequestration is important.

Supporter Spotlight

But according to Young, increases in ultraviolet light result in decreases in plant biomass. In other words, plants don’t grow as much. If there had been no Montreal Protocol, the ozone could have been depleted and the Earth’s plants exposed to more ultraviolet light. This would not only hinder their ability to sequester carbon, but would result in less plant biomass over time, which further decreases the amount of photosynthesis that can occur.

“So, the photosynthesis itself takes up less carbon dioxide, but also as the plants get smaller, because they’re growing less, then there’s less of them as well to take up more carbon dioxide,” Young said. “You end up with this vicious cycle.”

Young and his team focused on two modeled scenarios. The first was the “world projected” scenario, which accounts for the Montreal Protocol and depicts its effects on the climate through the end of this century. The other was the “world avoided” scenario that essentially assumes that the Montreal Protocol never happened and that CFC levels continued to grow by 3% per year.

The results, said Young, are conservative. They did not model a situation wherein the plants die of exposure to ultraviolet light, as other researchers might have done. In their models, plants grow less and less productive with increased exposure. Additionally, they had to allow for some variability as they scaled up to the global level. The Earth’s surface is highly differentiated, and different ecosystems would likely be affected by ultraviolet light at varying rates.

Carbon cycling

Though the Montreal Protocol allowed us to dodge the world avoided scenario, sequestered carbon faces other climate change-related threats. Disturbances can release carbon from where it is stored and make it available for conversion back to carbon dioxide. According to Dr. Christopher Osburn, North Carolina State University professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences, these disturbances are largely characterized by storms, sea level rise and land-use changes.

Big storms flush landscapes of carbon, transporting it through streams and rivers to slower-moving, receiving waters like estuaries. Estuaries have longer residence times. That means the water doesn’t turn over as quickly, allowing for organic carbon to be converted back to atmospheric carbon dioxide.

In 2019, Osburn published a paper in Geophysical Research Letters about this process by looking at how Hurricane Matthew affected carbon cycling in North Carolina. He estimated that in the two months following Hurricane Matthew, the Pamlico Sound and the Neuse River estuary released a combined 79,000 metric tons of carbon dioxide. That is equivalent to the annual emissions of 17,000 cars.

While the effect of storms on carbon storage is significant, direct human activity also influences carbon storage in North Carolina.

“Long-term changes in land use, where we alter the hydrology, we alter the land cover, can also facilitate and may exacerbate these problems,” Osburn said.

‘A proven case’

Coincidentally, Young’s paper comes on the heels of the International Panel on Climate Change’s 2021 report, which contained a particularly dour assessment of the future of the climate. It is possible, said Young, to find a streak of hope in his Montreal Protocol paper: The treaty itself is a proven case of research and action on an international level, with results that effectively protected the ozone and battled climate change.

But, Young said, there is so much still to be done.

“The future can be different, the past could have been different,” Young said. “And that in itself, I think, is something we need to hold on to.”