Over the last few months, eastern North Carolina has experienced the extremes of both drought and flooding – in some areas at the same time.

Although the two may seem opposites, state Drought Management Advisory Council Chairman Klaus Altertin explained in a recent interview that areas can have drought and flooding simultaneously. That’s because droughts take months to develop as below-normal rainfall continues week after week, whereas one storm can drop a week’s or a month’s worth of rain in a day, resulting in short term-flooding.

Supporter Spotlight

Determining whether a location is in a drought is complex because so many factors such as rainfall, temperature, time of year, duration of shortfall, need to be considered, Altertin said.

There is not a specific amount of rain that can change drought status. The designations are relative to the amount of rainfall considered normal for a location, the time of year and the overall conditions.

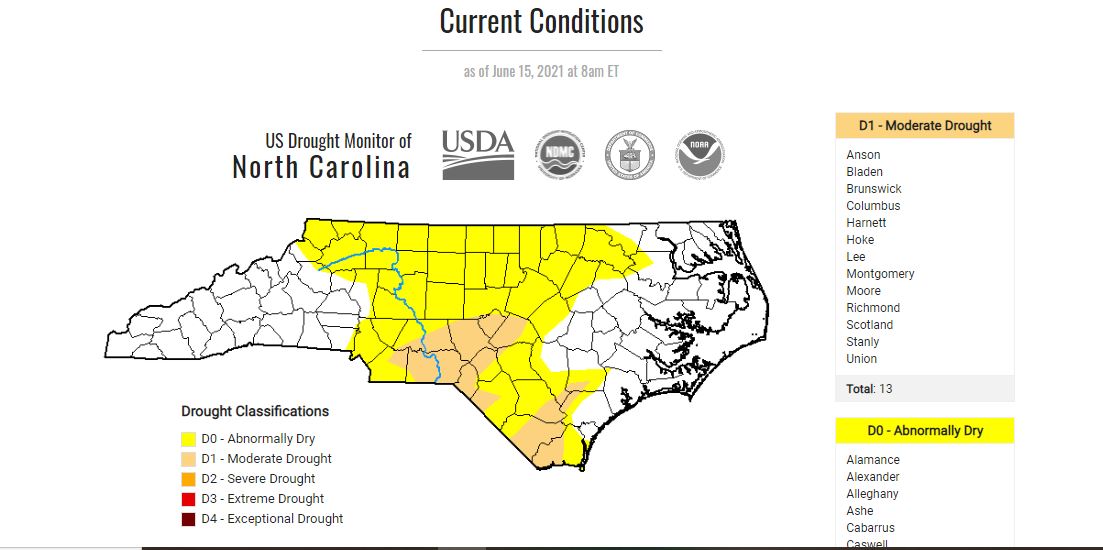

There are five drought levels — abnormally dry, or DO; moderate drought, or D1; severe drought, or D2; extreme drought, or D3; and exceptional drought, or D4. These levels are determined by the Drought Management Advisory Council, or DMAC. In general, 2 to 3 inches of rainfall in one week will be enough to improve conditions by one level.

The council meets every Tuesday to review past conditions and determine whether drought is developing or abating across the state. Once the council reaches a consensus, its members send their recommendations to the U.S. Drought Monitor for incorporation into the national map, Altertin said.

The council is made up of representatives from the U.S. Geological Survey, National Weather Service, Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Department of Agriculture, the state Department of Public Safety and the State Climate Office, Division of Water Resources, North Carolina Forest Service, the State Climate Office and other similar agencies and organizations.

Supporter Spotlight

Altertin explained that one challenge of the process, as specified by the U.S. Drought Monitor, is that the council can only consider conditions up to 8 a.m. Tuesday mornings, as the national maps are released on Thursday mornings.

“It can be raining while the DMAC is discussing the map, but they can’t include that rain in the decision making,” Altertin explained.

The council has a bit of a lag since its decisions are based on past rainfall and aren’t supposed to include a forecast component, but rainfall that causes flooding will often result in an improvement in the drought category the following week.

“It’s easy to get confused when you see an area announce severe drought the same week they get 5 inches of rain. Part of it is timing and part of it is the variability of rainfall in North Carolina,” Altertin said. “Typical rain events in the summer here tend to drop heavy rain in blobs or bands so even if the DMAC could consider the forecast, they couldn’t predict which area would get the rain and which would miss out. The event a couple of weeks ago was unusual. We don’t see those kind of rainfall totals, and as evenly distributed, without a tropical storm.”

Assistant State Climatologist Corey Davis with the North Carolina Climate Office told Coastal Review that drought can be one of the most complicated weather hazards, “since, unlike a thunderstorm or hurricane, it can be tough to see it coming, tough to measure it while it’s happening, and tough to know when the threat has ended.”

Davis said a drought is generally defined as a sustained lack of precipitation that’s either severe enough or long-lived enough to cause impacts such as crop damage in agriculture, wildfires in forestry and declining water supplies in water resources.

As droughts stretch on for weeks or months, some of the main effects observed are declining groundwater levels and deeper soil moisture levels, Davis said.

“While a big rain can help with that, during those events, we usually see heavy amounts falling over a fairly short time period, especially during tropical storms. This can bring a lot of moisture right at the surface, like to streams and topsoil, but at a certain point, those become saturated and the rest of the water just runs off, and it may never infiltrate deep into the ground where it’s really needed,” he said.

Because of this, many may find that they have big puddles in their backyard after a thunderstorm moves through, but their well may still be low if in a drought.

Davis said he often emphasizes that there’s more to drought than just dry weather.

“For instance, as we move into the spring and summer, if you go a few days without rainfall, your lawn may start to look yellow or brown in spots, but that doesn’t mean you’re in a drought. However, if you have consistently missed out on precipitation for several weeks or months and you can’t plant anything in your garden because the soil is too dry, that’s often a sign that you’ve gone beyond normal seasonal dryness and have entered drought,” Davis said.

Davis said that in the world of drought monitoring, “we often look at precipitation deficits over the course of three months, six months, or even 12 months. So 2 inches of rain in an afternoon is a lot, but if you’re 8 inches below normal over the past six months, that one event (even if it produces flooding) won’t fully resolve that deficit and its associated longer-term impacts.”

Davis said the amount of rain needed to recover from a drought depends on location and time of year. For example, Phoenix averages about 8 inches of rain per year, so drought may emerge if they’re an inch or two below normal, and an inch or two of extra rain may be enough to end that sort of drought.

“In North Carolina, a 1-inch deficit is a drop in the bucket compared to our annual average precipitation, which ranges from about 45 to 60 inches, depending on where in the state you’re at. We’re also more sensitive to precipitation deficits in the spring and summer, when evaporation rates are higher, and impacts can emerge more quickly than during our cool season,” Davis said.

Davis pointed to the recent drought as an example.

“Much of the coastal plain was anywhere from 3 to 8 inches below its normal precipitation this spring, so we would have needed around those amounts to fully recover. And we’ve largely seen those sorts of totals, or even greater ones, so far in June. Wilmington exited the spring 7.2 inches below normal, and it has been a little over 6 inches above normal so far in June, so it is now out of drought, and not even classified as Abnormally Dry on the U.S. Drought Monitor.”

Davis said a general rule is that 2 inches of rain in a week is usually enough to improve by one drought category, such as going from Severe Drought (D2) to Moderate Drought (D1). However, there are exceptions, he said.

The cycle of flooding and drought this year is an example of what to expect under climate change. Most projections show the state and a good chunk of the Southeast generally getting wetter, with more average precipitation per year.

“This stems from basic physics: evaporation and water-vapor content increases as temperatures warm, and that more-saturated air in turn produces more precipitation. While that may make it seem like droughts should become less common, we also expect to see and are seeing a change in our overall precipitation pattern,” Davis said. “More rain is falling in fewer events, and we’re seeing more intense dry spells and droughts between these rain events. These ‘flash droughts’ can be exacerbated by hot weather, which of course is another consequence of climate change.”

Looking at how the weather has played out so far this year, the state started 2021 with an especially wet winter — the 12th wettest on record statewide dating back to 1895 — then went into the ninth-driest spring, and are now on pace for a record wet June in some spots.

“The Wilmington area started the year with four days where at least an inch of rainfall was recorded between January and March. Then in April and May, Wilmington never had more than half an inch of rain on a single day, and it had stretches of nine days, 11 days and 12 days in a row without any measurable rainfall, so Severe Drought emerged there,” Davis explained. “Since June 1, Wilmington has already seen another four days with more than an inch of rainfall. These alternating cycles of very wet and very dry are already happening, and expected to continue in a changing climate.”

The drought categories are determined on the historical frequency of occurrence. Davis said that abnormally dry conditions would be expected to occur about 30% of the time, moderate drought about 20% of the time. An exceptional drought should occur only about 2% of the time.

“So if we see a particular weather station is running a springtime precipitation deficit of 3 inches, we can compare that with historical observations and determine roughly how rare of an event that is, which can help identify the local drought category there,” Davis said. “Classifying drought requires more than just rainfall data, though. Impacts are equally, if not more, important, and for each drought category, there are associated impacts we look for. Entering Moderate Drought (D1), for instance, we expect to see some reports of crop damage and water restrictions. For Severe Drought (D2), those impacts become crop losses and water shortages.”

The U.S. Drought Monitor uses a “convergence of evidence” approach, which means multiple indicators and impacts are considered to set a particular drought category.

“As an example, it’s not unusual to have drier weather in the fall, and some farmers may delay harvesting until a bit of extra rain comes along to finish maturing crops for the growing season. But based on that sort of report alone, we wouldn’t call it Moderate Drought if other indicators, such as recent precipitation and streamflows, were all roughly in the normal range,” he said.

Often during a drought, Davis said they are asked when and how will the drought end.

“I usually answer that we don’t know when, but we probably know how, because it’s usually a tropical storm or hurricane. With Claudette moving through this past weekend, it seems like that will be the case for many areas this time as well,” he said. “But even still, we can’t rule out drought sticking around in some areas this summer. We’ve still got the hottest part of the year ahead of us, and it’s not uncommon for some parts of the state to miss out on rainfall this time of year, at least when we don’t have a tropical storm bearing down on us.”

He said that for the western part of the state, in both 2016 and 2019, the worst drought conditions didn’t emerge until September and October. Those events were also unique in that the coast had seen heavy rain and flooding from Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and from Hurricane Dorian in 2019, while parts of the mountains were in extreme drought.

This is another way to think about the question, “how can we have flooding if we’re in a drought?” Davis said. “North Carolina is a big, diverse state both geographically and meteorologically, so it’s very possible to have both drought and flooding happening at the same time in different areas.”