Hurricane season ceased to be theoretical in eastern North Carolina coast early last week, with rip tide warnings issued for northern beaches as Tropical Storm Bill formed far offshore and then veered away to the northwest.

That storm had a minor impact, but as Tropical Storm Claudette bears down on the region from the west, there’s no let up of worry. For a coastal economy already flagging from a year of shuttered restaurants and canceled bookings, any storm-related downtime would be doubly harsh.

Supporter Spotlight

There is a similar and powerful worry inland, away from the beach houses and rough surf where the television crews set up. Recent major storms showed that it is in the low-lying lands along the networks of coastal plain creeks and rivers where water does the most damage.

The river towns, especially along the Neuse, Lumber and Tar-Pamlico systems, are still reeling from the last decade’s cascade of catastrophes.

The named storms are just part of the flooding threat in these towns. As the state’s warmer, wetter climate drives more frequent heavy rains, deluges are doing repetitive damage in vulnerable areas across the state, including places like Kinston, where this past winter’s rains inundated areas also submerged during Hurricane Matthew.

With broad agreement between the legislature and the governor’s office to address the problem and a potential surge in federal funding to scale up the response, scientists, planners and policymakers are trying to create a blueprint for flooding mitigation and resilience that they can take statewide. To do that, they first have to figure out what works.

Understanding Stoney Creek

There are no silver linings to hurricanes, but there are a lot of lessons to learn. In the hardest of ways, North Carolina has gotten especially good at predicting where floodwaters will rise by tracking in real time innovative flooding models during storms and relaying that information to emergency responders.

Supporter Spotlight

As powerful a tool as those predictive maps have been during emergencies, they are also emerging as an important source between storms, driving long-term policy to build more resilient communities.

Among an array of projects and studies funded in recently introduced legislation to develop a statewide plan on flooding is a large-scale trial of strategies developed to mitigate a persistent critical threat when Stoney Creek in Goldsboro jumps its banks.

It would be difficult to find a threat from flooding easier to grasp than when roads to a hospital become impassable. That’s what happens when the waters of Stoney Creek start to rise alongside Goldsboro’s cluster of health care facilities between N.C. 13 and the U.S. 70 bypass. They include Wayne UNC Health Care, the county’s main hospital.

The creek, which is part of a roughly 30-square-mile watershed, starts in northern Wayne County farmlands near Eureka and wends through the heart of Goldsboro, passing near the medical centers and then through a light industrial and commercial zone before flowing into the Neuse River near Seymour Johnson Air Force Base.

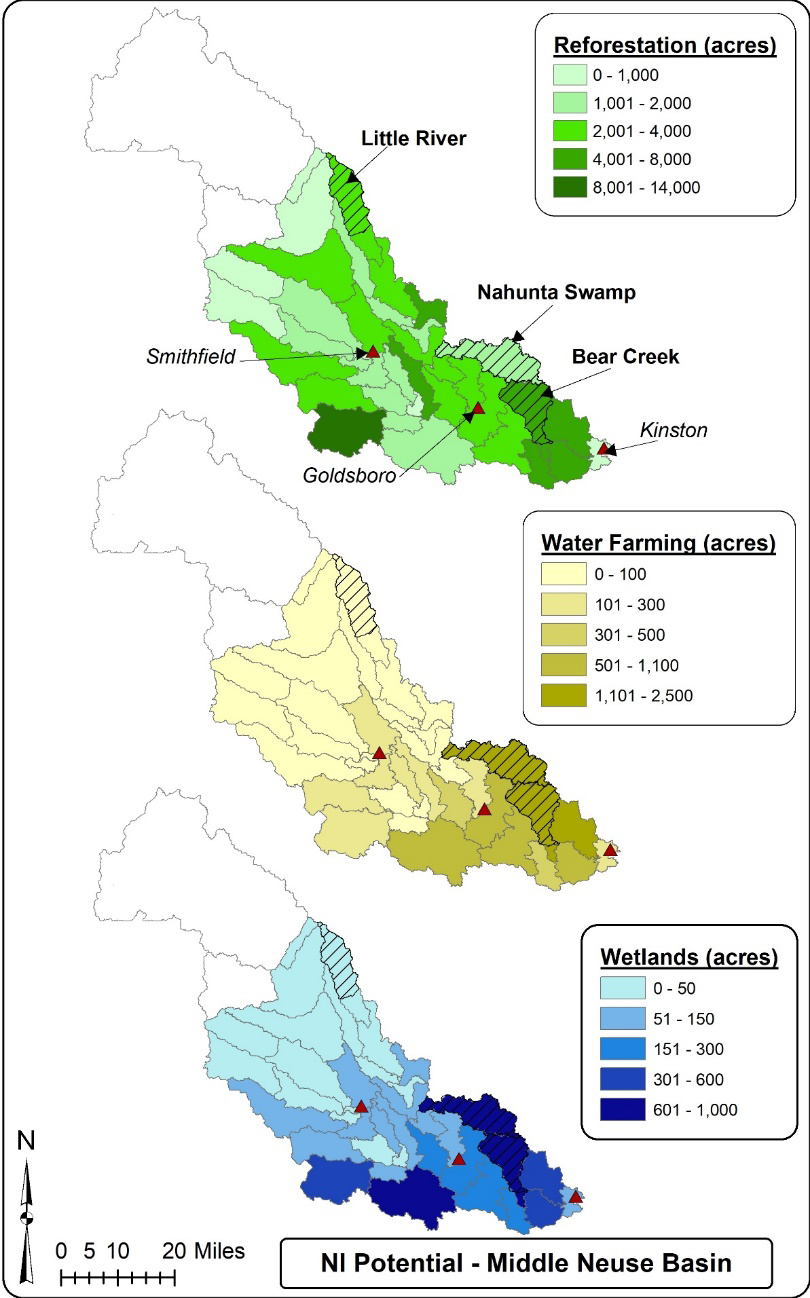

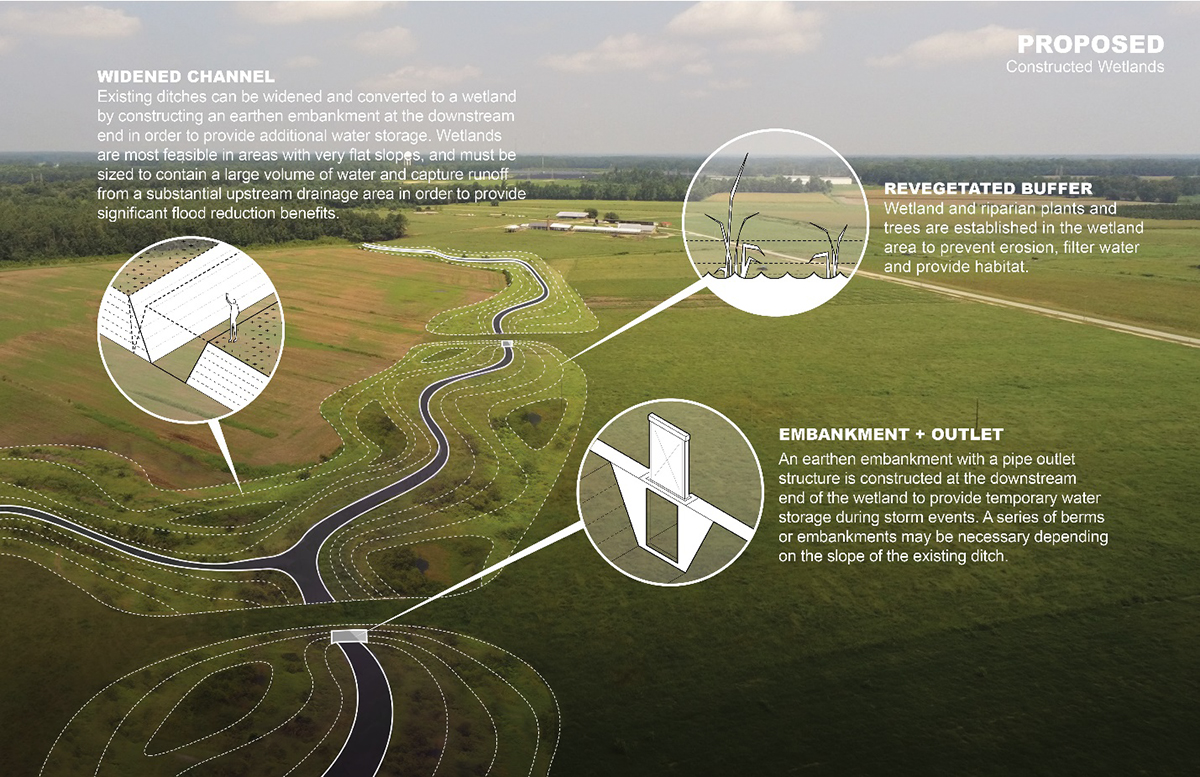

Barbara Doll, a North Carolina State University engineering professor and one of the state’s leading researchers in resilience strategies, said the Stoney Creek project is an attempt to understand the actual impact of resilience strategies like restoring wetlands, reforesting farmland and improving road crossings. Her team built detailed models of soils, land use and other data points throughout the entire watershed and each sub-basin within it.

“We did a lot of ground-truthing and refining,” she said. “I’ve seen a lot of work where people just come and they overlay soils and land use and some other layers and they say, ‘here’s where you want to restore a wetland,’ and they have no numbers for how much flow reduction there is to that,” Doll said in an interview with Coastal Review earlier this year. “So, we said, ‘let’s look where actually it really would work to do these things and how would you have to design them and what would this water storage on farms look like.’”

They picked farmland sites in the upper watershed where there was actual potential for conversion, lands that were less productive or already out of use due to flooding. Then they mapped how much water could be held back under different types of storms and strategies and what those combinations meant downstream.

The revelations of what Doll calls “getting into the nuts and bolts” of resilience and mitigation were both promising and sobering.

For the larger storms, the 500-year storms like Hurricane Matthew and Hurricane Florence, the capacity of the water storage system is overwhelmed. But for the large deluges and even the 100-year storms, the plan would shave between 1 and 2 feet off the height of the floodwaters, with the biggest impact near crossings closest to the hospitals. Throughout the watershed dozens of structures, homes and businesses, would remain above the waterline.

There are three basic solutions to dealing with the floods damaging home and businesses and washing out roads in places like Goldsboro, Doll said. You can engineer your way out of by raising roads and improving culverts, you hold back the water, or you can move people and structures out of the way.

Many places in eastern North Carolina are faced with a losing battle, she said, where the only reasonable long-term solution is to get people and structures out of harm’s way.

One goal of the Stoney Creek project is to give communities a more realistic set of tools to understand the costs and benefits of mitigation and resilience.

Both the state House and Senate are looking at major flood legislation this year, including roughly $30 million for a handful of projects in priority watersheds. Stoney Creek is among those and is considered the pilot project for the state’s natural and working lands effort. House Bill 500 earmarks about $5 million for land acquisition to kickstart the Stoney Creek plan.

Will McDow, Resilient Landscapes director for the Environmental Defense Fund, said the Stoney Creek studies are important in developing an accurate tool for planning.

“I think this study provides a kind of a clear example of how the state can use and build upon its existing science and data and models to help communities understand what are their options to reduce the flood impacts that they’re feeling,” he said. “Before this study, the community clearly knew that when it rained a 100-year event, their hospital was getting cut off, but they didn’t know how much water needed to be held back. Once you know how much water needs to be held back, then you can really begin to have the different conversations about how you might do that.”

Resilient Routes, Water Farming

One part of Doll’s resiliency work has been to assess the effectiveness of rebuilding roads and overpasses.

It makes sense, Doll said, for the state to put the funds into raising a road like I-95, but in many cases “engineering the way out” of the problem is fiscally unlikely. “It gets expensive, and it takes time,” she said.

What the Stoney Creek project showed, she said, was that in some cases a natural and working lands solution can be cheaper and more effective.

By holding back water upstream through a combination of reforestation of farmland and allowing some specified fields to flood, Doll’s team determined that three of the seven key creek crossings around Goldsboro’s hospital area would be prevented from washing out in a major storm.

That work has helped sharpen the focus around so-called “resilient routes,” critical roads for evacuations, supplies and emergency response.

“We can’t do every road. We can’t size them all to the 100-year storm and so we create these resilient routes and really work to protect them,” she said.

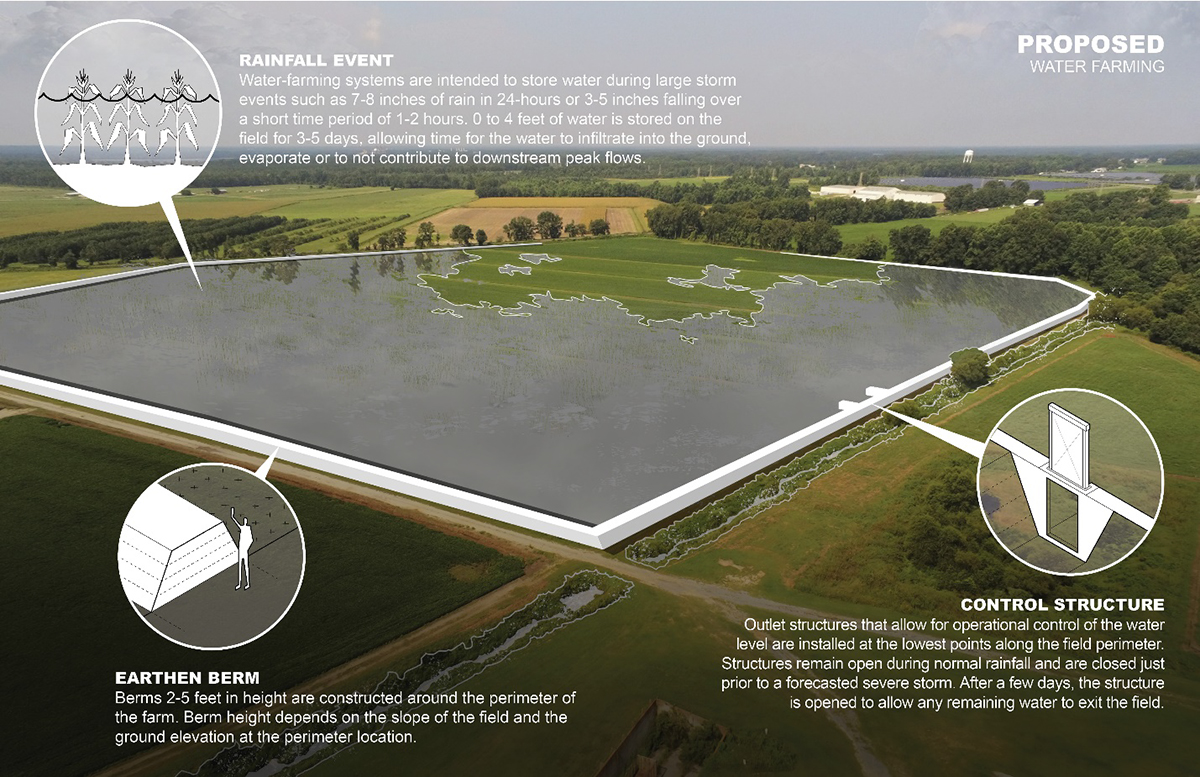

Doll said using natural and working lands solutions will mean different things in different places. The Stoney Creek project benefits from a sizable amount of farmland upstream of Goldsboro where the slope of fields is only 1% or less. With a little engineering, including constructing a berm, the 1% fields can hold a considerable amount of water, she said. “These low-lying lands provide a lot of opportunity.”

Since they’re often the same fields that tend to flood or that farmers can’t get to because of high water, Doll said that working out a way for farmers to be compensated for allowing their fields to hold back water makes sense.

“Why not store some water on these lands and have that farmer compensated so they know they’re going to get their investment back,” she said. “We call it water farming. They’re being paid to farm water for certain events. I think that could be a great assurance to them.”

North Carolina Farm Bureau Natural Resources Director Keith Larick, who has been working with Doll and others to develop the plan, said farmers he’s talked to are open to the ideas, especially considering the amount of damage they seen both from major storms and more frequent flash flooding.

“People don’t really know what the program is going to look like yet,” he said. “There are a lot of ideas out there as far as how are you going to fund something, who decides what gets built, is it a state program or more of a local program.”

The idea of water farming might be new, but farmers are used to incentive programs like those for conservation practices. Whatever is developed has to be flexible, he said.

“Some of these practices that we’re talking about may not take land out of production permanently,” he said.

You could have a case where a field only needs to be used occasionally to hold floodwaters, Larick said. In that case the farmer would get the payment for water farming, but during other years could keep working the land.

“We’re trying to be creative and flexible when we talk about these kinds of things to come up with something that works for landowners but also accomplishes the goal of helping with flood issues.”