The Environmental Protection Agency rebooted earlier this year its climate change website.

As part of an “update” announced April 2017 by the Trump administration, the climate change website from the previous administration was archived. The EPA relaunched its climate change website in March of this year under Biden-Harris administration’s commitment to take action on climate change and restore science, according to a release.

Supporter Spotlight

“Climate facts are back on EPA’s website where they should be,” said EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan in a statement. “Considering the urgency of this crisis, it’s critical that Americans have access to information and resources so that we can all play a role in protecting our environment, our health, and vulnerable communities. Trustworthy, science-based information is at the foundation of strong, achievable solutions.”

The EPA for the first time in four years has a webpage “to guide the public to a range of information, including greenhouse gas emissions data, climate change impacts, scientific reports, and existing climate programs within EPA and across the federal government,” according to the agency. The climate change website includes information on greenhouse gas emissions data, climate change impacts, scientific reports and existing climate programs.

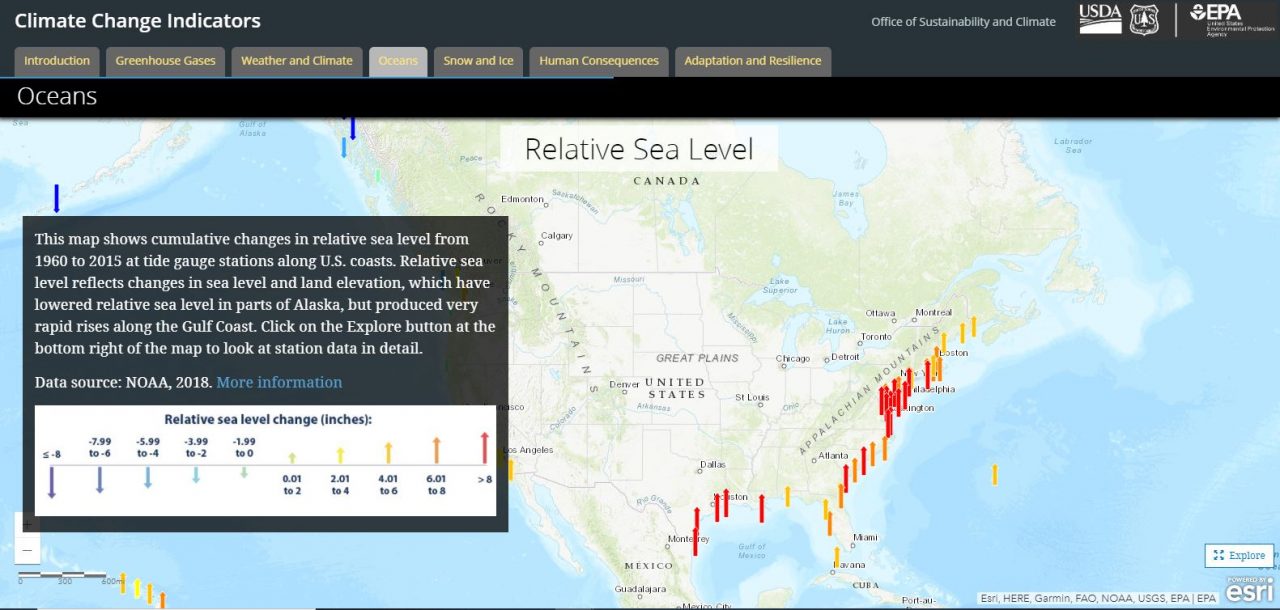

The agency announced in May the relaunch of the Climate Change Indicators in the United States website, a part of the climate change website, that “presents compelling and clear evidence of changes to our climate reflected in rising temperatures, ocean acidity, sea level rise, river flooding, droughts, heat waves, and wildfires, among other indicators.”

A dozen new indicators and several years of data have been added to the revamped resource. Climate change indicators are the status of specific environmental or societal conditions of a specific area and time. The website details indicators on greenhouse gases, weather and climate, oceans, snow and ice, health and society, and ecosystems.

Indicators show that global temperatures are increasing, sea level is rising, tidal flooding is more frequent, and the growing season has increased by more than two weeks, according to the agency. Indicators also help the National Climate Assessment and other efforts to understand climate change.

Supporter Spotlight

“EPA’s Climate Indicators website is a crucial scientific resource that underscores the urgency for action on the climate crisis,” said Regan in the May release. “With this long overdue update, we now have additional data and a new set of indicators that show climate change has become even more evident, stronger, and extreme — as has the imperative that we take meaningful action.”

The site features interactive data-exploration tools graphs, maps and figures, plus how climate change can affect human health and the environment. More than 50 data contributors from various government agencies, academic institutions, and other organizations developed the climate change indicators, each of which was peer reviewed.

Effects of several of these indicators can be observed in coastal North Carolina, including sea level rise, increased storms, flooding and rising temperatures.

Michelle Allen, project manager for the North Carolina political affairs team for the Environmental Defense Fund, said she sees the EPA climate indicators as confirmation of what North Carolinian’s know all too well: “Climate change is happening and it is affecting our daily lives through impacts like more extreme heat days that put our kids and workers at risk, more non-storm flood events, and increasingly severe and frequent storms that cost our state billions, putting lives and livelihoods at risk.”

Allen said she sees this relaunch as a call to action. “Climate change is already affecting our state in a tangible way, which is why we need swift, bold action to both curb the carbon pollution driving climate change, and make our communities more resilient to impacts we are already experiencing.”

As for warming temperatures, according to the EPA indicators, 2016 was the warmest year on record, 2020 was the second warmest, and 2010-2020 was the warmest decade on record since 1880, when thermometer-based observations began. Additionally, the occurrence of heat waves is increasing, from an average of two heat waves per year during the 1960s to six per year during the 2010s.

This means the possibility of hotter days and more frequent and longer heat waves could lead to an increase in the number of heat-related illnesses and deaths. The frequency or severity of extreme weather events, such as storms, could increase the risk of dangerous flooding, high winds, and other direct threats to people and property.

Autumn Locklear, climate health epidemiologist with the state Department of Health and Human Services, said in a weekly heat health report that from May 30 to June 5, there were 43 emergency department visits for heat-related illness. Of those, 65% were male, mostly 25-44-year-olds. Heat exhaustion was the most common heat related illness diagnosis. Emergency department visit notes point to working outdoors and recreation as causes.

Heat-related illnesses are not new here in the state. The Department of Health and Human Services warned in late July last year that since May 2020, there were 1,205 heat-related hospital emergency department visits. In 2019, from May 1 to Aug. 31, there were 3,692 emergency department visits for heat-related illness, similar to the summers of 2017 and 2018, the North Carolina Division of Public Health reports.

Most of those visits were by 45-64-year-old males on the coast and in the Piedmont, men who were either working outdoors or recreating when they became ill. Prolonged exposure to heat can lead to dehydration, overheating, heat illness or death. Additionally, extremely hot days may also coincide with poor air quality that can increase the threat to those living with chronic health conditions, older adults and children, as previously reported.

The EPA notes that the rate of sea level rise has accelerated in recent years to more than an inch per decade. The changes in sea level are relative and vary by region.

“When averaged over all of the world’s oceans, sea level has risen at a rate of roughly six-tenths of an inch per decade since 1880,” according to the EPA. Between 1960 and 2020, indicators show that sea level has risen along most of the U.S. coastline, especially along the mid-Atlantic coast and parts of the Gulf Coast, where some stations registered increases of more than 8 inches.

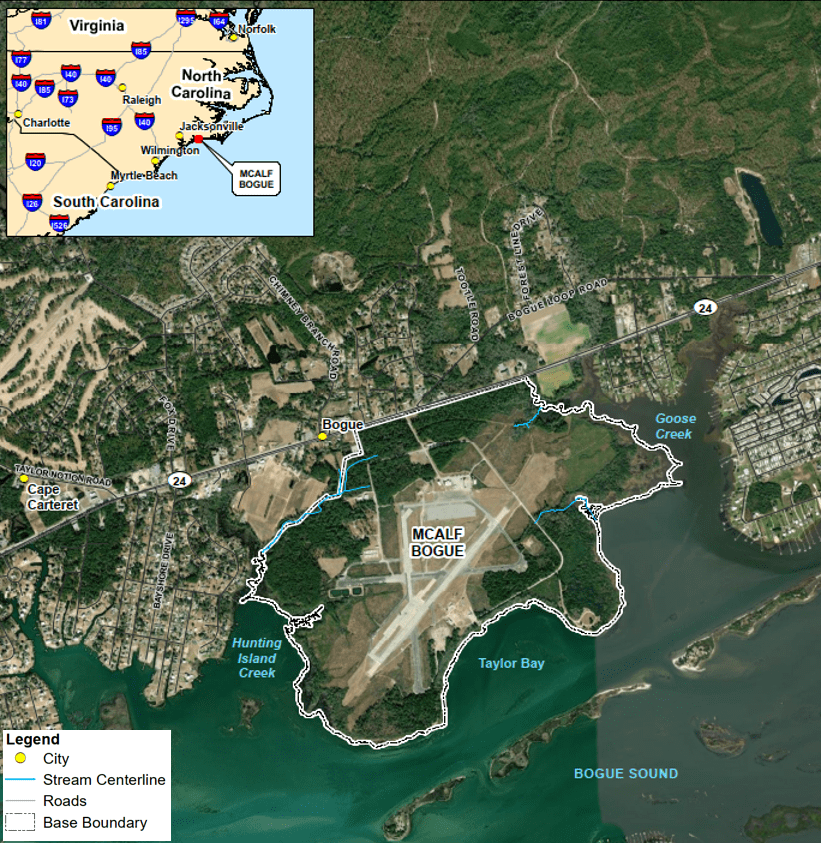

Along the North Carolina coast, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts sea level trends to rise, although they vary according to location. For Duck, the relative sea level trend per year is 4.79 millimeters; for Oregon Inlet Marina, the trend is 5.32 mm; Beaufort is 3.29 mm; Wilmington is 2.56 mm; and Southport is 2.01 mm.

A consequence of sea level rise is that salt water can inundate low-lying wetlands and dry land, erodes shorelines, contribute to coastal flooding, and increases the flow of salt water into estuaries and nearby groundwater aquifers.

Four independent studies show that the amount of heat stored in the ocean has increased substantially since the 1950s, which not only determines sea surface temperature, but also affects sea level and currents, according to the EPA. Plus, the warming waters are causing marine species to move into cooler or deeper waters. The shifts have occurred among several economically important fish and shellfish species.

The Biden administration has made several commitments to tackle climate change, such as setting a goal to reduce by 50-52% greenhouse gas pollution from 2005 Levels in 2030 and rejoined the Paris Agreement, a change from the previous administration.

In April 2017, the Trump administration, as part of a stated effort to update the agency’s website, reviewed several EPA websites, according to officials, to reflect the agency’s new direction under President Donald Trump and Administrator Scott Pruitt. Officials committed to review content related to climate and regulation in the release.

“We want to eliminate confusion by removing outdated language first and making room to discuss how we’re protecting the environment and human health by partnering with states and working within the law,” J.P. Freire, associate administrator for public affairs, said at the time.

A nonprofit watchdog group, the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative, in a January 2018 report on the changing digital climate after the Trump administration took office, described the alterations to the EPA’s climate change website as “the most significant reduction in access to an agency’s climate change information.”

“The Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) removal and subsequent ongoing overhaul of its climate change website raises strong concerns about loss of access to valuable information for state, local, and tribal governments, and for educators, policymakers, and the general public,” according to the report.

The Washington Post reported that the climate change website deletion occurred within 24 hours of the People’s Climate March on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., and nationwide. The march was organized in opposition to Trump’s rollbacks of the Obama administration’s climate policies.

Allen with the Environmental Defense Fund noted that Gov. Roy Cooper had set ambitious climate goals for North Carolina, adding that the state needs bold new policies to meet those goals and put North Carolina on a path toward averting the worst effects of climate change.

“If carefully designed, these policies can make emissions reductions more cost-effective and affordable, and drive positive economic development across the state,” she said, citing a recent report by Duke University and the University of North Carolina. That study found that a program called the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative can help North Carolina reduce emissions while lowering overall costs, reducing the state’s reliance on fossil fuels and improving public health through reduced air pollution.

The findings also underscore the importance of making the state more resilient to changes already happening, she said.

“State leaders must also act to address existing impacts, such as improving our resilience to flood and storm events,” said Allen.