After more than two years and a multitude of tests, North Carolina researchers are chipping away at getting answers to questions about a host of chemical compounds in drinking water sources, food and air.

The teams of researchers, collectively referred to as the North Carolina Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) Testing Network, or PFAST Network, submitted to the North Carolina General Assembly on April 15 their report, the results of which were discussed in an online forum held Tuesday evening.

Supporter Spotlight

The report is part of a legislative mandate to address the public’s concerns about PFAS contaminants in the state and the potential health effects the chemical compounds have on people, wildlife and the environment. It includes recommendations for more monitoring, research studies and regulations.

One of the studies focused on drinking water sources across the state.

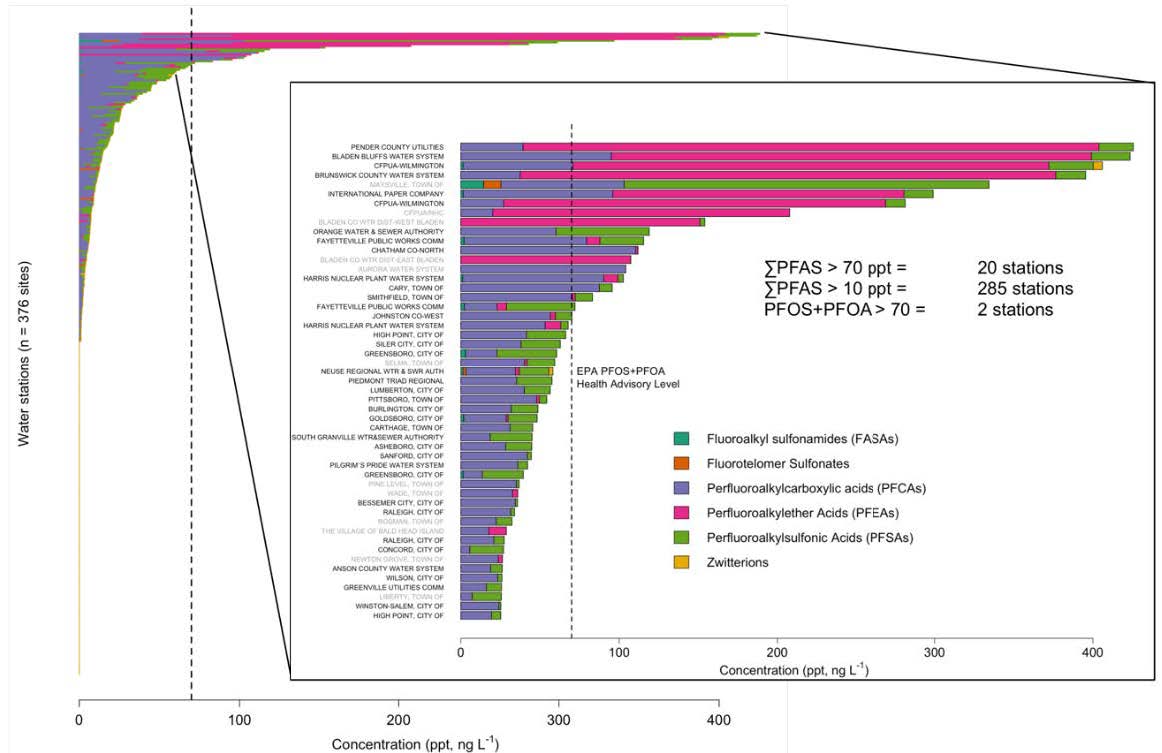

Over two and a half years, researchers sampled all municipal and county water systems – 376 sites in all – for PFAS in raw drinking water.

Researchers specifically looked for 48 individual PFAS and perfluorooctanoic acid, or PFOA, in those samples and found that 20 of those sources contained concentrations of PFAS at or above the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s health advisory limit for PFOA and perfluorooctane sulfonate, or PFOS.

Of the top half of those with the highest total PFAS concentrations, nine were in the Cape Fear River basin.

Supporter Spotlight

PFAS concentrations in drinking water sources from the lower Cape Fear region were “considerably higher” than concentrations of the chemical compounds in drinking water sources nationwide, according to the report.

The Cape Fear River basin is the largest watershed in the state. It is the drinking water source to about 1.5 million North Carolinians, about 1 million of whom are affected by water with the higher PFAS concentrations, said Detlef Knappe, a North Carolina State University professor and researcher.

PFAS levels are higher in that area because the compounds have been discharged from the Chemours Fayetteville Works facility into the Cape Fear River since the 1980s.

PFAS are synthetic chemicals that are resistant to heat and are water, grease and stain repellent used in a host of consumer products, including carpets, carpet cleaning products, food packaging, furnishings, cosmetics, outdoor gear, clothing, adhesives and sealants, firefighting foam, protective coatings and nonstick cookware.

There are nearly 10,000 individual PFAS.

Levels of these chemical compounds varied in drinking water sources throughout the state.

“We see a trend of relatively low concentrations in most ground water drinking water sources in eastern North Carolina and western North Carolina,” said Lee Ferguson, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering at Duke University.

Studies show that there is an overall trend in the Piedmont and central part of the state for higher concentrations of PFAS in drinking water sources because the water supply in those areas comes from surface waters.

Higher concentrations of PFAS were also found in the Haw River and Neuse River.

Ferguson noted that a single groundwater well that was once the drinking water source for Maysville, a small town in Jones County, contained relatively high concentrations of PFAS.

That well was subsequently shut down by town officials after they were notified of the high levels of PFAS. The town has since switched to the county’s water service.

More than 4,000 of the more than 5,000 private well samples collected were found to have PFAS contaminants, Knappe said.

There are regulated contaminants and unregulated contaminants, the latter of which there is no national standard so water utilities cannot say whether water containing these chemicals is safe to drink.

Jamie DeWitt, an associate professor at East Carolina University, and her team have been studying the immunotoxicological and developmental immunotoxicological effects of PFAS.

Her research team examined the effects of PFAS in mice.

DeWitt explained Tuesday that their research thus far has shown that short chain compounds appear to rapidly excrete from the body. That was the case with perfluoro-2-methoxyacetic acid, or PFMOAA, one of two compounds the team introduced to lab mice.

The other, Nafion byproduct 2, a longer compound, stayed in the body. Side effects of the compound included liver weight gain.

“We still have a lot of work to do,” DeWitt said, adding that it takes time to look at each individual compound.

In her March 24 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies, DeWitt discussed the health effects of PFAS.

“A comprehensive evaluation of the toxicological data for 14 PFAS compiled by the Agency for the Toxic Substances and Disease Registry reported a wide variety of undesirable health effects in people exposed because they work with PFAS, live in areas with high levels of PFAS in the environment, or even from everyday activities,” she said. “These health effects include effects on the liver, the cardiovascular, endocrine, immune, and reproductive systems, and on development. Some populations have seen increases in kidney and testicular cancer. These undesirable health effects also have been observed in experimental animals exposed to individual PFAS through food, water, or skin, which are supportive of these findings of undesirable health effects in humans.”

Such health effects are being observed at levels below the EPA’s health advisory limit of 70 parts per trillion, she said.

Another study examining of the effects of PFAS in aquatic life reveals that PFAS bioaccumulate in fish and reptiles, in this case American alligators.

Scott Belcher, an associate professor at N.C. State University, told the audience of about 100 who tuned in to the virtual forum Tuesday that elevated levels of nearly a dozen PFAS were found in the blood of striped bass in the lower Cape Fear River.

Blood samples were collected from fish and alligators below Lock and Dam No. 1. They ranged in age between 2 and 7 years old.

Most of the PFAS detected in the blood samples was PFOS.

When compared with striped bass and alligators in other, area waters, including the Lumber River basin and Lake Waccamaw, abnormal blood cells were observed only in the animals sampled in the Cape Fear River.

Belcher said researchers found lupus-like characteristics in alligators, such as poorly healing lesions.

“We’re really building this case in the evidence pointing toward differences in the animals that may be resulting in autoimmune-like diseases,” he said.

The testing network has made 60 recommendations in its report to legislators, including testing to better understand PFAS sources in the Cape Fear River and Neuse River basins with special emphasis on the Haw River basin, further toxicological studies, including studies on compounds most frequently detected and detected at the highest concentrations, and further studies on effective ways to remove PFAS from water sources.

The report also includes two major recommendations: continued funding for statewide PFAS research and clearly citing data used when creating future guidance, policies, or regulations.