Co-published with Carolina Public Press

Think of it as a link in a chain.

Supporter Spotlight

This one starts below the streets of a college campus, where people wrapped in personal protective equipment collect human waste from pipes snaking from student dormitories.

Just 24 hours after those samples are collected, test results reveal whether SARS-CoV-2, better known as the coronavirus, is present.

This coronavirus surveillance system was implemented at Appalachian State University in an ongoing pilot project launched earlier this fall and aimed at detecting COVID-19 at its earliest stages and then pinpointing those infected with the virus.

The university in Boone began collaborating in October with Rachel Noble and her team of researchers at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City to set up a coronavirus tracking system.

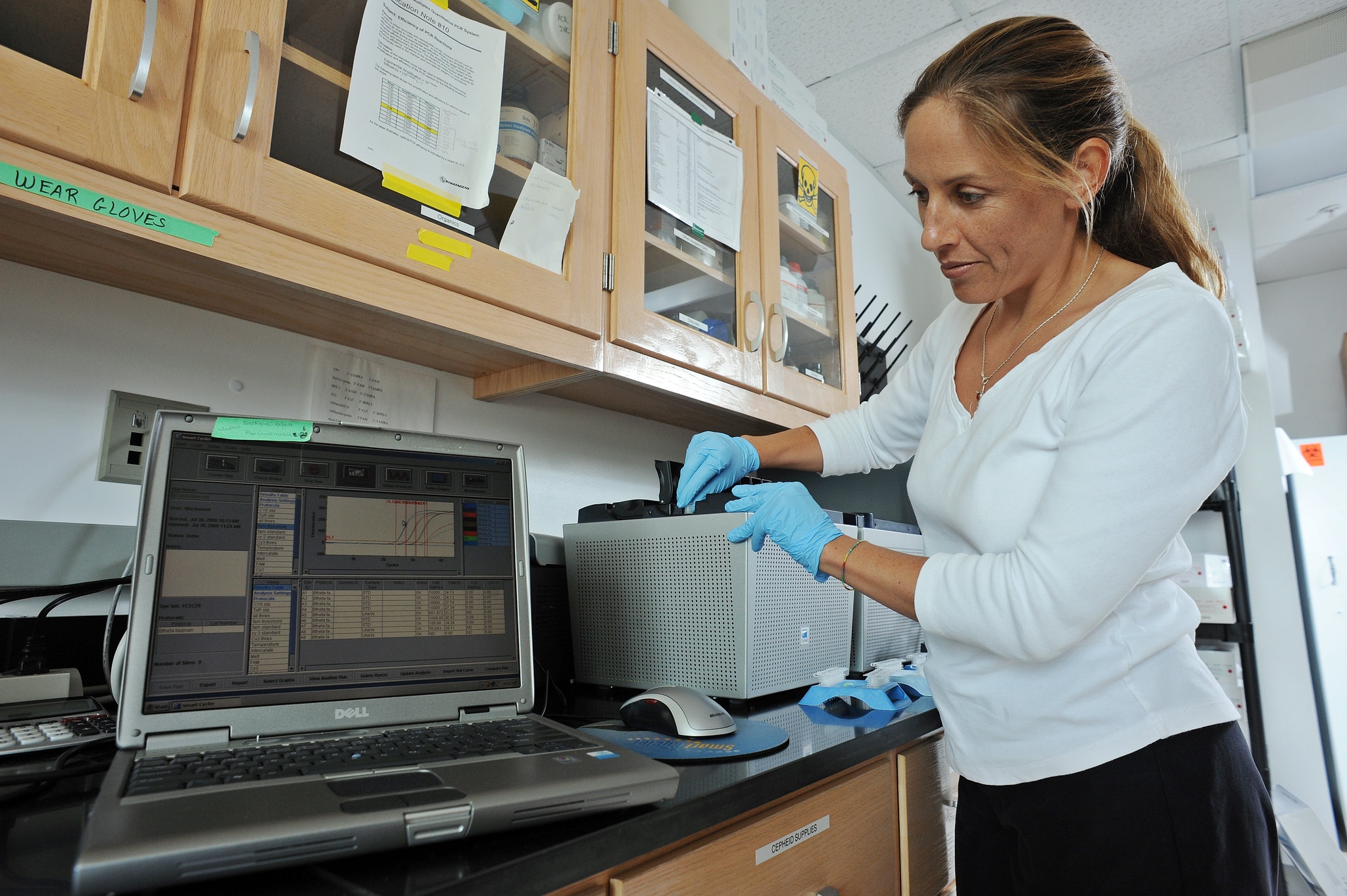

Noble, a professor of marine and environmental microbiology, is at the helm of research that aims to get an overall picture of where and how coronavirus is being spread in North Carolina by tracking COVID-19 pathogens in wastewater.

Supporter Spotlight

The pilot project at ASU initially entailed collecting wastewater from what’s called the lateral line – the sewage pipe that routes waste from a building to a main line that carries the waste to a treatment facility – of seven student dormitories.

Those samples were then shipped from the mountains to the coast, where Noble and her team filtered the waste, putting it through a purification process before screening for the virus.

Not exactly like the nasal swab testing being done throughout the country, “but we’re looking for the exact same thing,” Noble said.

“This is just now being used in a different format in a slightly different way,” she said. “Instead of having people file in in a single-file line to get tested, whether it’s on a campus or whether it’s at an Amazon distribution center and workers are waiting to start their workday, or whether it’s an elementary school or in a town, the idea is the same in that it takes time and money to get individual people tested, and you can use pools or aggregate testing approaches to determine how many people in your system are ill. The wastewater, if you look at it just kind of as pedals on a flower or layers in a cake, it becomes just a layer or just a petal of the entire program.”

In March, Noble and her team began working with town, city and county officials across the state to collect samples from wastewater systems and test those samples for the virus.

Samples from those plants are taken over a 24-hour period, which gives researchers an aggregate measure of what’s going on in that population.

The project at App State is a little different, Noble said, because samples are not taken as often, rather, two to three times a week.

That’s still enough to track the virus.

“You can begin to build an idea of whether people in those buildings, in this case dormitories, are actually sick,” she said.

“It’s not perfect. It’s the same as any sort of nasal swab. It’s not like we can measure the difference between zero and one virus. There’s definitely a detection limit. Whenever people come up and they see a positive result I’m very confident in positive results because the methods are very specific to SARS-CoV-2. If you get a positive, you have ill individuals in the system. If you get a negative, you cannot rule out the fact that there was either excess water in the waste, meaning it got diluted out, or there was excess ‘chunky stuff’ or you just didn’t measure it because it was below the detection limit<” Noble continued. “We’ve been working very hard to improve the recovery of the method, but it’s not perfect and so that’s something we hope to work on in the future. Nobody’s coronavirus methods are perfect or even close to being perfect. We’ve been doing the work for some time now, so I think we’ve achieved the goals that we were set up to achieve for the pilot study.”

Ece Karatan, professor and vice provost for research, molecular microbiology, at ASU, credited Noble and her team for the fact the pilot project was up and running within a week.

“Part of that was Dr. Noble and her team sharing with us some mistakes to avoid,” she said. “For example, we never had to work out when do we sample. When’s the best time to sample. A lot of the issues that arise in any new project we were able to avoid because we had extensive discussions with Dr. Noble and her team and took advantage frankly of her expertise. We had to home in our timing. We had to home in on the number of samples collected. We had to home in what time we could start and the best time we could start. Those are logistic issues that were fairly easy to address.”

Perhaps one of the biggest challenges of the pilot project was getting the samples from the university to the lab.

“Shipping to eastern North Carolina is never easy, but we deal with that all the time,” Noble said. “My lab team was highly, highly resourceful in that way. Instead of waiting for the trucks to come to us to deliver the package, my lab manager decided that we should actually drive there and be there when the package arrived in the morning, literally when the plane flew in or the truck arrived, depending on the location. That saved us probably four, five or six hours of waiting.”

Universities that conduct wastewater tests to detect COVID-19 may share the results of those tests with students, who may then get individually tested.

“What’s good is that the virus can be shed in feces and urine and can be detected before symptoms can emerge,” Karatan said.

ASU researchers are now in the second phase of the project, analyzing results through Dec. 31, Karatan said.

Students living on campus left for winter break around the Thanksgiving holiday. Wastewater samples were also collected from some non-dormitory buildings after the fall semester ended.

Karatan declined to discuss test results.

More than 1,280 coronavirus cases have been reported at ASU, according to The New York Times, which is tracking cases on U.S. campuses through a rolling survey.

As of Dec. 11, 50 campuses in North Carolina reported more than 13,600 cases, according to the Times.

Earlier this year, 14 UNC system schools received $29 million from the UNC-Chapel Hill-based North Carolina Policy Collaboratory to fund 85 research projects focusing on treatment, testing and prevention of COVID-19.

“We have a longer-term vision here,” said Noble, who has been conducting research on wastewater testing to detect viruses for more than a decade. “It’s not just working today on COVID. It’s that this technology has the possibility to prevent, I’m not going to say it’s going to prevent a future pandemic, but it could prevent the scale of something like this happening again because we would be much better informed at the very beginning and that’s really what this is all about is thinking bigger than just the practical things that we’re doing on a daily basis.”