Dec. 16, 2020, marks the 150th anniversary of the first lighting of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus, including his findings pertaining to the lighthouse and its history.

America’s celebrated historic structures may not be as ancient as many of the world’s classic architectural masterpieces, but our iconic buildings are no less venerable. Among our best-loved, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse has, since 1870, stood majestically as a sublime symbol and standard-bearer of our nation’s lighthouse heritage.

Supporter Spotlight

For a century and a half, the nation’s tallest brick sentinel has watched over the dynamic place we call the Outer Banks of North Carolina — a place of unlikely historical paradoxes, a small area where great moments of American history have taken place.

The Outer Banks are narrow, fragile, restless, yet, improbably, they have for eons resisted the relentless assaults of the insatiable Atlantic.

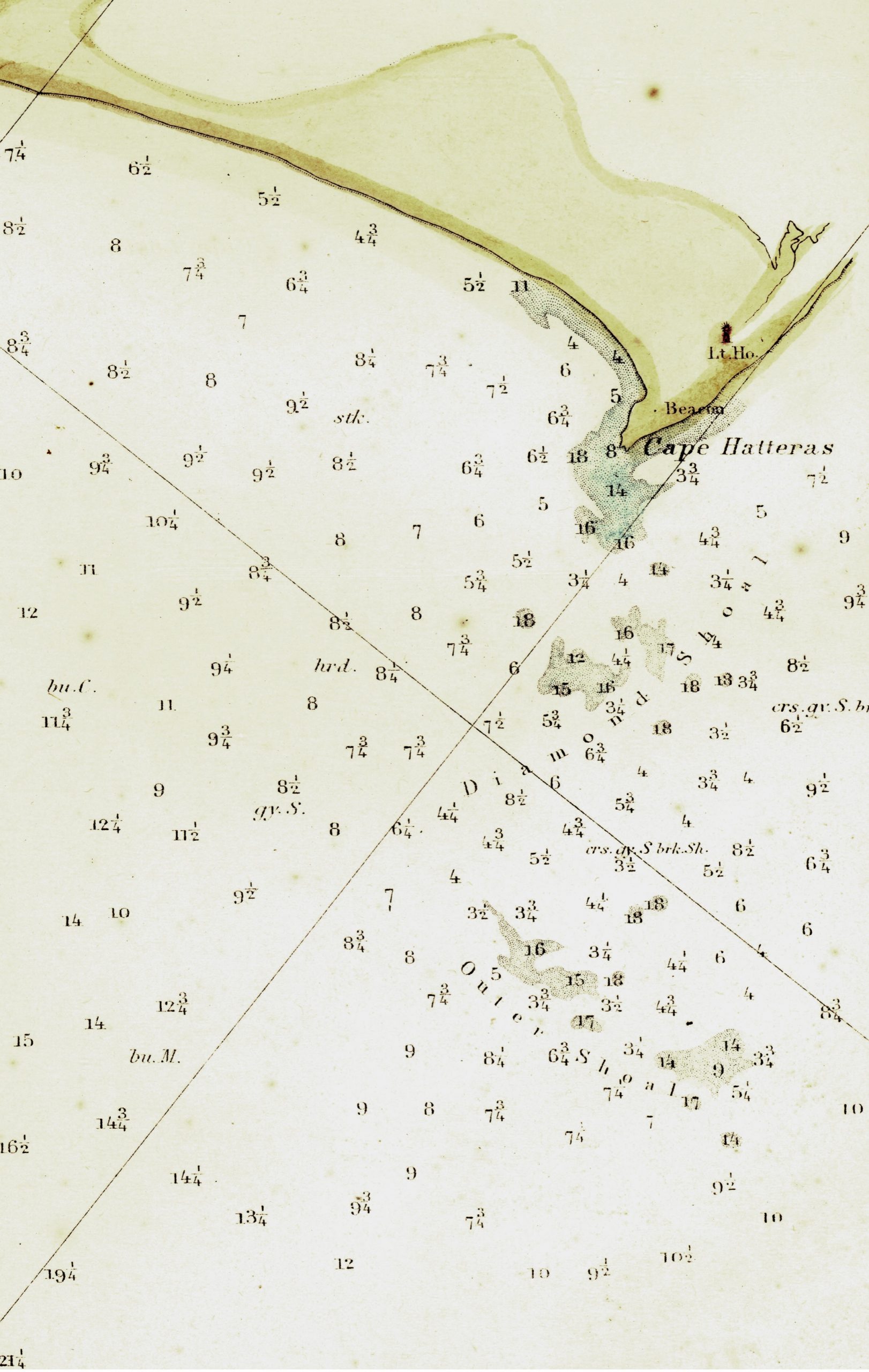

These sandy, windswept islands were once one of the most remote and least populated places in eastern America, yet for 500 years, legions of explorers, seafarers and invincible navies have attempted to pass within just a few miles of its shores through one of the world’s busiest and most dangerous ocean passages.

In the days of sail, not all mariners were lucky enough to escape the Graveyard of the Atlantic and the clutches of that gauntlet of chaotic waves marking Cape Hatteras and Diamond Shoals — Neptune’s toll gate, where fares were steep and men’s lives were cheap.

Throughout its history, Cape Hatteras’ magnificent lighthouse has endured catastrophic storms, witnessed unparalleled lifesaving rescues and stood as a silent sentry over deadly military conflicts.

Supporter Spotlight

Twice, world wars have stained these shores with oil and blood.

In 1918, within the reach of the lighthouse’s guiding light about 14 miles to the southeast, the Diamond Shoals Light Vessel No. 71 was sunk by gunfire from Imperial Germany’s U-boat U-140. All 12 crewmembers of the lightship escaped in their lifeboat and six hours later landed on the beach not far from the lighthouse and their homes.

Twenty-four years later, more than 65 German U-boats returned, this time with a vengeance, and with the objective to sever vital supply lines supporting the planned Allied invasion of Europe by sinking merchant ships, many within just a few miles of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. In North Carolina waters alone, 93 ships were sunk or damaged and more than 1,700 people were killed, including many civilians.

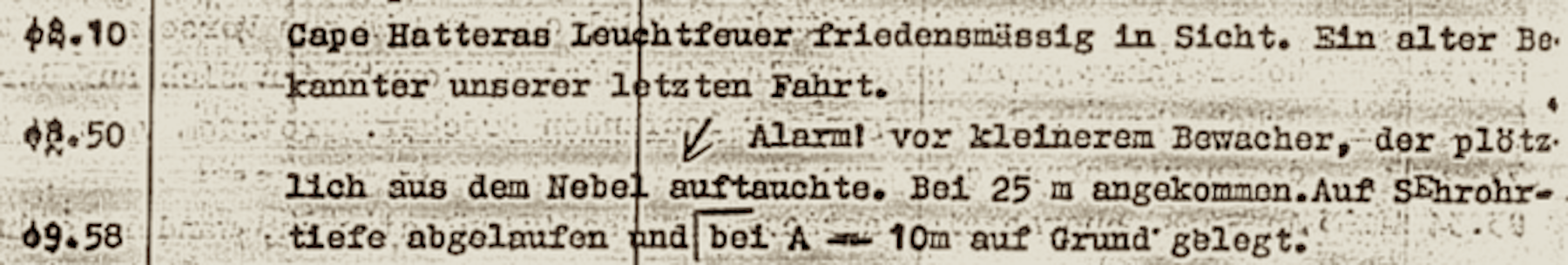

Using the lighthouse to guide them, fearless German U-boat skippers stalked their prey with impunity. “Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is in sight — our old acquaintance from our last patrol,” U-123’s Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen wrote in his war diary in March 1942, although at that time he was seeing the light flashing atop a temporary steel tower along Buxton’s Back Road while the brick tower continued to serve mariners as a daymark and the Coast Guard as a lookout post.

In a surprisingly brief period of just a few months, scores of merchant sailors drowned or burned to death near Cape Hatteras during torpedo attacks on the ships City of Atlanta, Venore, Empire Gem, Dixie Arrow and numerous others.

Ill-fated sailors jumped from their ships into flaming waves of oil while Coast Guard rescuers watched, powerless to save them. Visible from 75 miles away, towering columns of black smoke from burning oil served as the victims’ ephemeral headstones above their watery graves. In the poignant words of Byron: “Un-knelled, un-coffined, and unknown.”

Some survivors made it ashore, including a group of terrified Norwegian sailors who were found at dawn sheltering under the lookout tower near the lighthouse after landing at the cape unseen by sleepy “sand pounders” patrolling the beaches.

And on March 30, 1942, about 40 miles due east of the lighthouse, a baby was miraculously born in a lifeboat after his mother escaped from the torpedoed passenger freighter City of New York. The infant’s rescue 27 hours later by a U.S. Navy destroyer improved morale aboard the warship; two weeks later its emboldened and resolute sailors sank the first German U-boat in U.S. waters about 30 miles northeast of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. Their victory signaled the beginning of the end of the battle of “Torpedo Junction.”

Shipwrecks and heroic, gold medal rescues were simply an ordinary part of life around Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. In 1884, Benjamin B. Dailey, Patrick Etheridge and other lifesavers who dwelled “upon the lonely shores of Hatteras,” bravely strapped on their cork lifebelts and put to sea in frightening and tumultuous surf exceeding the worst conditions the islanders had ever seen. Over a period of hours in frigid seas they succeeded in rescuing nine victims, minutes from death, from the foundering barkentine Ephraim Williams 5 miles east of Haulover Beach.

No less courageous were the women of the islands. At times when Cape Hatteras lifesavers launched their wooden surfboats and vanished into the open ocean through thundering waves and billows of spindrift, their families would establish a camp at the base of the lighthouse to await their loved ones’ fate. They knew that’s where the lifesavers would return — if they returned.

“When my mother was 6 years old,” remembered the late Beatrice McArthur of Buxton, “she and her brothers and sisters were moved out to the lighthouse for one or two nights in 1906 (for the rescue of the schooner Robert H. Stevenson). Other families were there too, and all the children played together. And at night they slept in the base of the lighthouse. They thought it was fun.” Worried that they might become widows before the next dawn, the wives of the lifesavers offshore surely did not share in their children’s good times.

Like their beloved, barber-pole-striped lighthouse, the inhabitants of Hatteras were steadfast, dependable, all-seeing and caring. Most resolute were the lighthouse’s long line of distinguished keepers. It has been said that lighthouse keepers feared not the devil nor his henchmen. These were men who placed their hand on the Bible and took a solemn oath to never leave their station regardless of weather or other acts of God.

Augustus C. Thompson comes to mind, the principal keeper who, perched in the watchroom 180 feet above the ground atop the unreinforced masonry tower, rode out the 1886 Charleston earthquake that rocked Cape Hatteras Lighthouse “backward and forward like a tree shaken by the wind.” Thompson reported to the U.S. Light House Board that “the shock was so strong that we could not keep our backs against the parapet wall, it would throw us right from it.” Thompson bravely held his post. Those were the days when men were men.

But the combined forces of weather and the Atlantic Ocean have been the lighthouse’s and its surrounding villages’ most formidable and relentless adversaries. Like a thief in the night, each time a storm moved out to sea it took a piece of Hatteras Island with it, and a piece of the hearts of the generations who had lived there.

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s longest serving and last principal keeper, Unaka Benjamin Jennette, was a man seasoned by salt spray, unrelenting storms and hard times. Along with his neighbors, Jennette experienced the Outer Banks’ version of the Great Depression, although, with a wink and a wry smile the proud islanders were quick to say, “It didn’t bother us at all. We were already depressed — how are you going to get any worse than that?”

From the top of the lighthouse on the morning of Jan. 31, 1921, Jennette peered through his spyglass at a five-masted schooner fetched-up hard on the middle shoal. When lifesavers were finally able to board the wreck after many failed attempts there was not a soul aboard and forevermore the Carroll A. Deering of Bath, Maine, has been remembered as the Ghost Ship of Diamond Shoals.

Jennette served as keeper through nor’easters and hurricanes too numerous to list but includes the back-to-back storms of 1933, which forced him to permanently relocate his family to the relative safety of Buxton village.

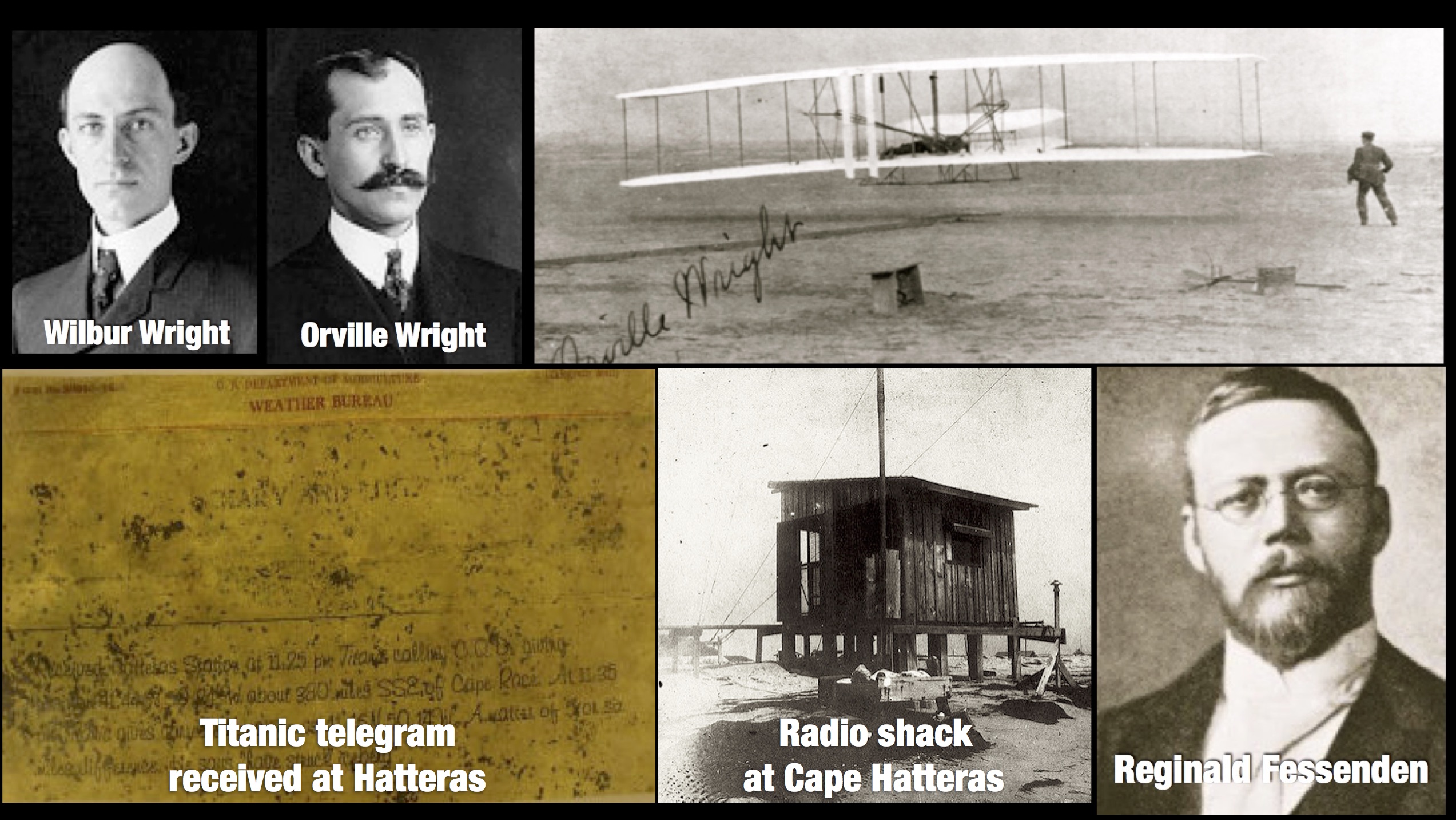

Jennette was a young man when the Wright brothers first took to the air in their flying machine and when Reginald Fessenden transmitted the world’s first musical notes broadcast from a tower at Buxton, less than a mile from the lighthouse. The keeper was newly married when a wireless operator on Hatteras Island was the first to hear a distress call from RMS Titanic. These were just some of the notable moments of our nation’s history made on these quaint Outer Banks.

Not much could trouble Cap’n ’Naka, as he was fondly called, except for the steadily encroaching Atlantic Ocean, plainly observed by generations of Cape Hatteras residents.

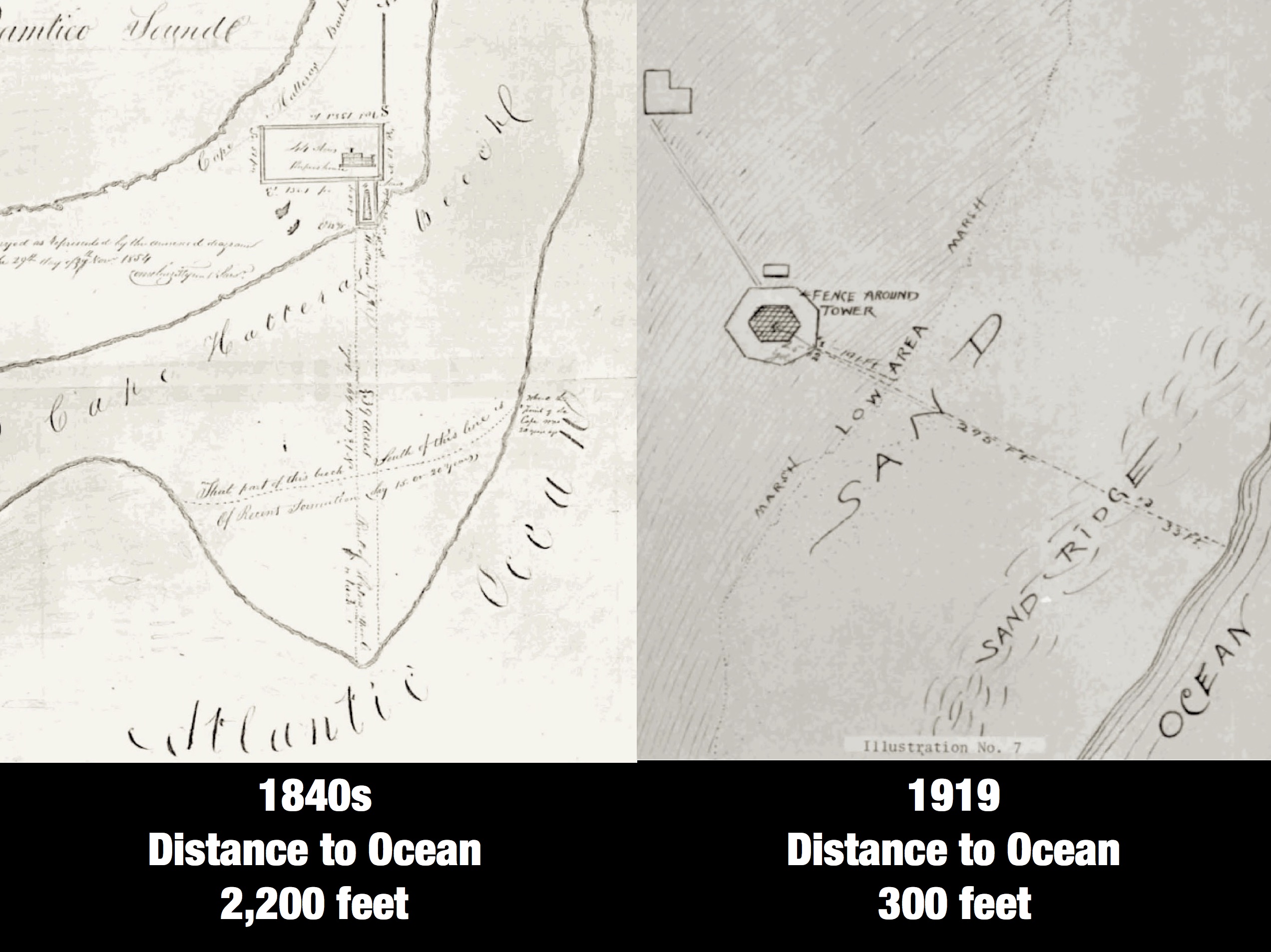

In 1832, according to U.S. Treasury Department reports published in “The American Pharos, Or Light-house Guide,” the lighthouse was, at that time, 1 mile from the ocean. Fewer than two decades later, when Cap’n ’Naka’s great-grandfather Benjamin Fulcher was keeper at Cape Hatteras in the late-1840s, the high-tide line had receded to just a half a mile away. On the day in 1919 when Cap’n ’Naka became the principal keeper at the lighthouse, the ocean’s waves were crashing just 300 feet from the base of the tower.

In 1936, the government abandoned the seemingly doomed tower for the next 14 years until a transitory accretion of the beach encouraged the Coast Guard to reestablish the light at the top of the preeminent landmark.

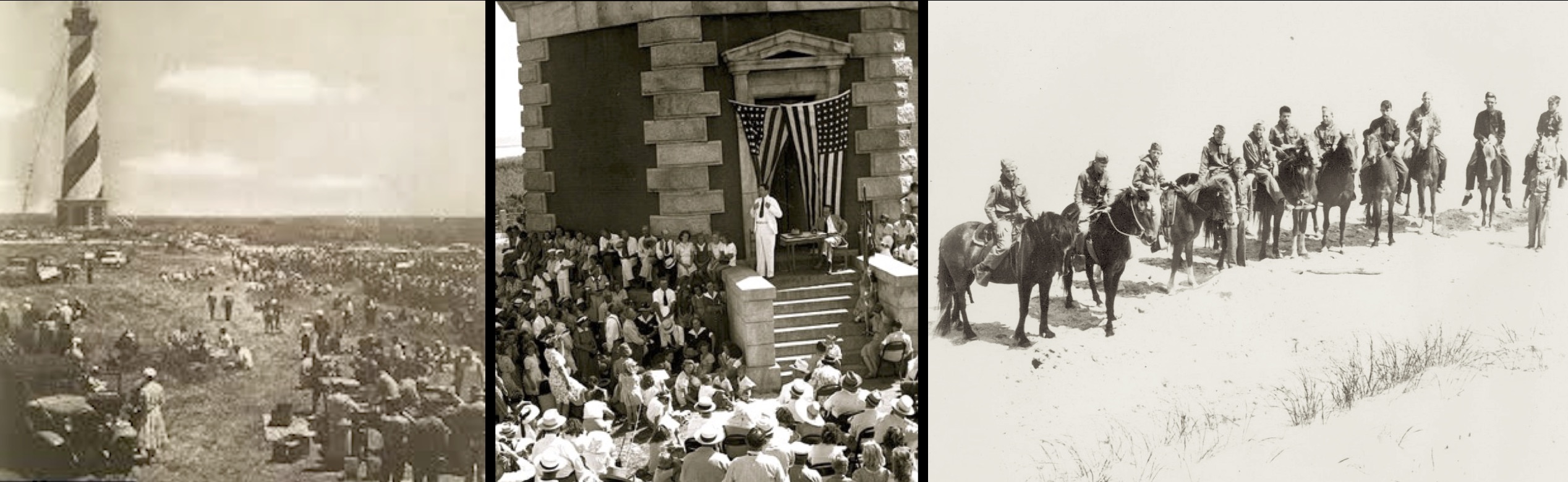

Happy days returned to the light station and islanders will always remember the Pirates Jamboree with its parade past the lighthouse featuring the nation’s only mounted Boy Scout troop from Ocracoke.

As time passed, license plates from all 50 states would be seen on cars parked at the Cape Hatteras Light Station, and many tourists would time their arrival to occur at sunrise.

The 1870 tower’s image became ubiquitous and represented the pride of its community on signs that welcomed visitors into the safe harbors of motels, restaurants and churches. Fishermen caught fish in its shadow, painters and photographers came to capture its image, and surfers and kiteboarders from across the country arrived to ride the waves at a mecca of East Coast beaches.

Storms never abated, however, and always seemed to come most often during holidays and religious observances — among them the Christmas Storm of 1884, the Ash Wednesday Storm, the Lincoln Day Storm, and the Halloween nor’easter of 1992 that stirred even the ghosts of the Graveyard of the Atlantic with its 34-foot-high waves lasting for 114 hours.

In 1980, during a rare March blizzard and under the cloak of swirling snow and piles of foam from spindrift, the covetous ocean claimed the blue-gray foundation stones of the 1803 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse.

Through it all, the mighty Cape Hatteras Lighthouse held her ground, yet over time, there was less ground to hold. During the worst storms, waves were seen crashing against the tower’s red brick base and rose-colored granite quoins and above the lighthouse’s massive gray cast-iron door. Would the grand old lighthouse sooner or later suffer the same fate as the foundation of the 1803 lighthouse?

After decades of concern and indecision, a commitment was made to save the lighthouse. With the stewardship and courage of the National Park Service, the genius of scientists and fearless structure movers, the unwavering support of the Outer Banks Lighthouse Society, and the good graces of the U.S. Congress and the American taxpayers, the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse got a new lease on life.

In 1999, the nation’s tallest, unreinforced brick lighthouse was lifted vertically 5.3 feet onto steel rails and was relocated 2,900 feet to the southwest, placing the lighthouse at the same relative distance from the ocean as when it was first built. It was an historic achievement, no less remarkable in its day than man’s first powered flight. The project was fondly called, the “Move of the Century.”

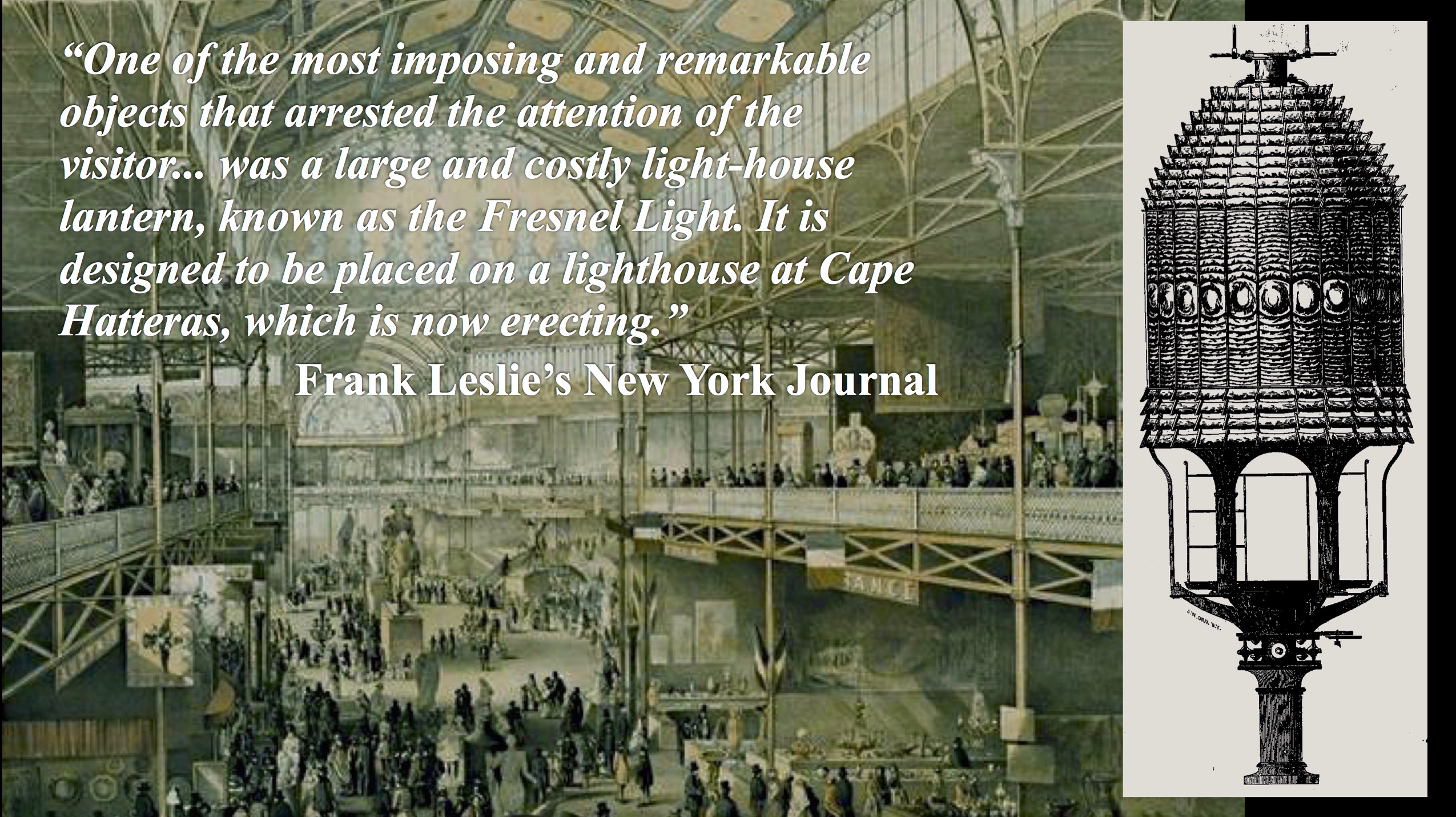

This story would be incomplete without adding that perhaps one of the most remarkable moments in the lighthouse’s history is the day in 1870 it received the first-order Henry-Lepaute Fresnel lens that was originally installed in the tower’s older sibling, the 1803 Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, prior to the Civil War. That lens, beautifully depicted in National Geographic’s 1933 Clifton Adams photo being proudly polished by Unaka Jennette, is arguably the most historically significant Fresnel lens in America.

This writer was the first to discover and report that, in 1853, that same lens was prominently displayed in the south nave of New York City’s Crystal Palace by the U.S. Lighthouse Board during the landmark Exhibition of Industry of All Nations — our nation’s first world’s fair.

The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse Fresnel lens was the second, first-order lens purchased by the government to systematically upgrade all the nation’s lighthouses in the 1850s – the whereabouts of the first, first-order lens originally installed in Florida’s Sand Key Lighthouse is, at this time, undetermined.

Removed from the lighthouse in 1861 by Unaka Jennette’s great-grandfather Benjamin Fulcher, of all people, and hidden throughout the Civil War, the lens was recovered, returned to France for repairs and stored at the Lighthouse Service’s Staten Island depot until the 1870 tower was completed.

For many years, at the top of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, the lens appeared as a diamond in the sky until it was replaced by a modern rotating aerobeacon in 1950. Today, what remains of the lens atop its enormous 1870 cast iron pedestal and clockwork mechanism can be viewed at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras.

And that, in a nutshell of sorts, is the story of America’s lighthouse.

Happy 150th birthday, Cape Hatteras Lighthouse!