Coastal Review Online is featuring the research, findings and commentary of author Kevin Duffus.

The second of a two-part series begins with the Cape Fear Lifesavers making their way to the wreckage of the Charles C. Dame on Oct. 13, 1893, on Frying Pan Shoals off Cape Fear. Read Part 1.

Supporter Spotlight

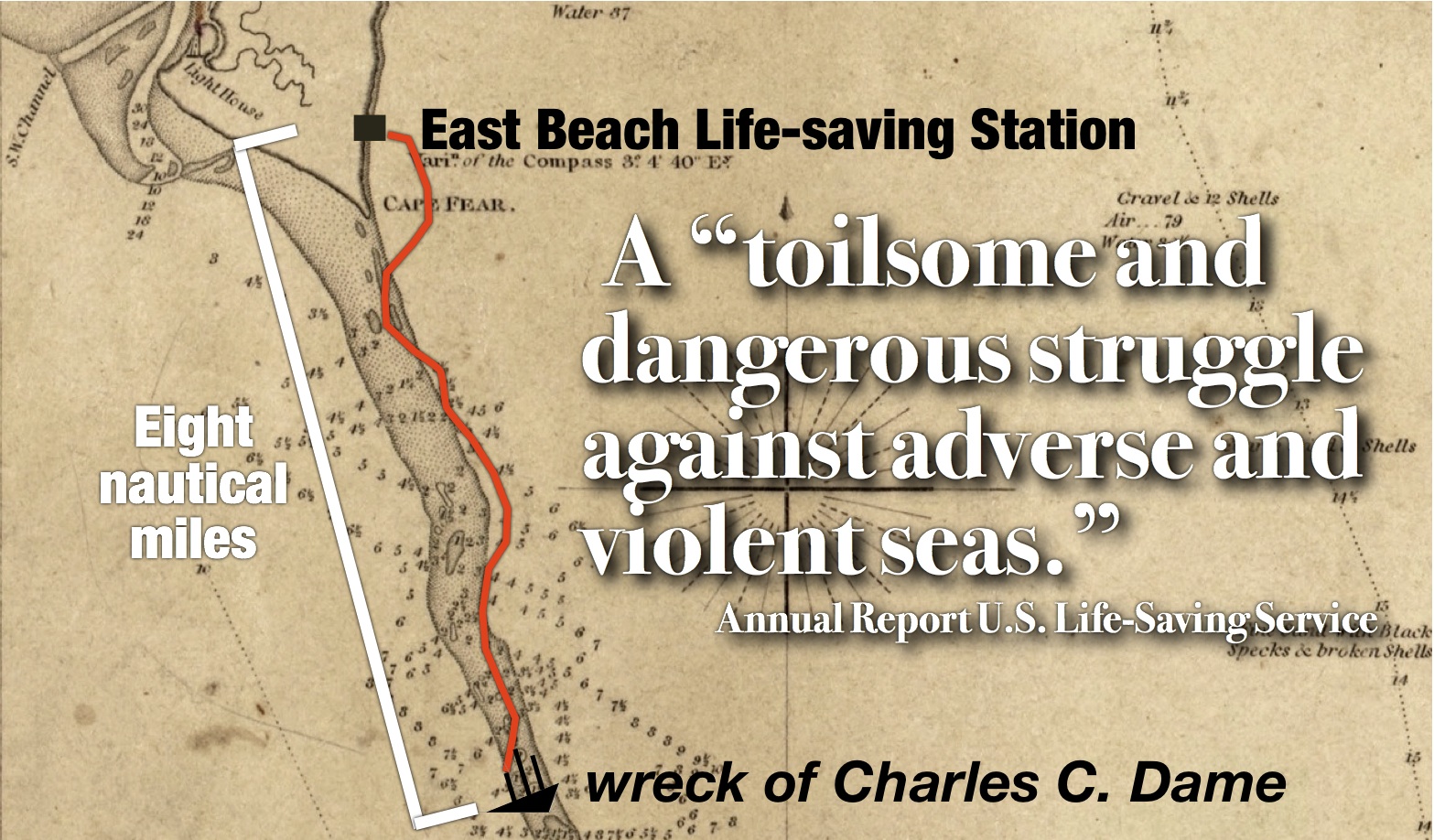

The stricken vessel, Charles C. Dame, was just 8 miles away, rapidly breaking apart on Frying Pan Shoals. But the unremitting waves and wind from the south slowed the Cape Fear lifesavers’ progress to less than one mile per hour.

For more than eight hours, the intrepid men of Cape Fear station suffered a “toilsome and dangerous struggle against adverse and violent seas” in order to reach the shipwreck. As they got closer, keeper John L. Watts could see the vessel had once been a three-masted schooner, but was no more. Only the lower portion of the foremast remained standing. The ship’s back was broken and the decks washed away.

Watts’s surfboat finally reached the scene of the disaster at 3 p.m. In his official report, the keeper wrote that “every sea was washing over her. The crew members were huddled together on the jib boom, the only place they could get clear of the sea.”

Watts shouted above the roar of the storm, “Who are you, from where do you hail?” The schooner’s master Samuel S. Grove hoarsely replied, “The Charles C. Dame, from Newburyport by way of Baltimore!”

The lifesavers learned that the schooner’s crew had been clinging to the jib boom for more than 12 hours and they were nearly at the end of their endurance. Grove told Watts later that “he had given up to be lost until the surf boat was seen.”

Supporter Spotlight

Watts knew that if he and his men did not act quickly, it would soon get dark and they might be forced to stay out most or all of the night, and by morning there likely would not have been anyone left to save. U.S. Life-Saving Service crews were never known to abandon shipwreck victims at sea.

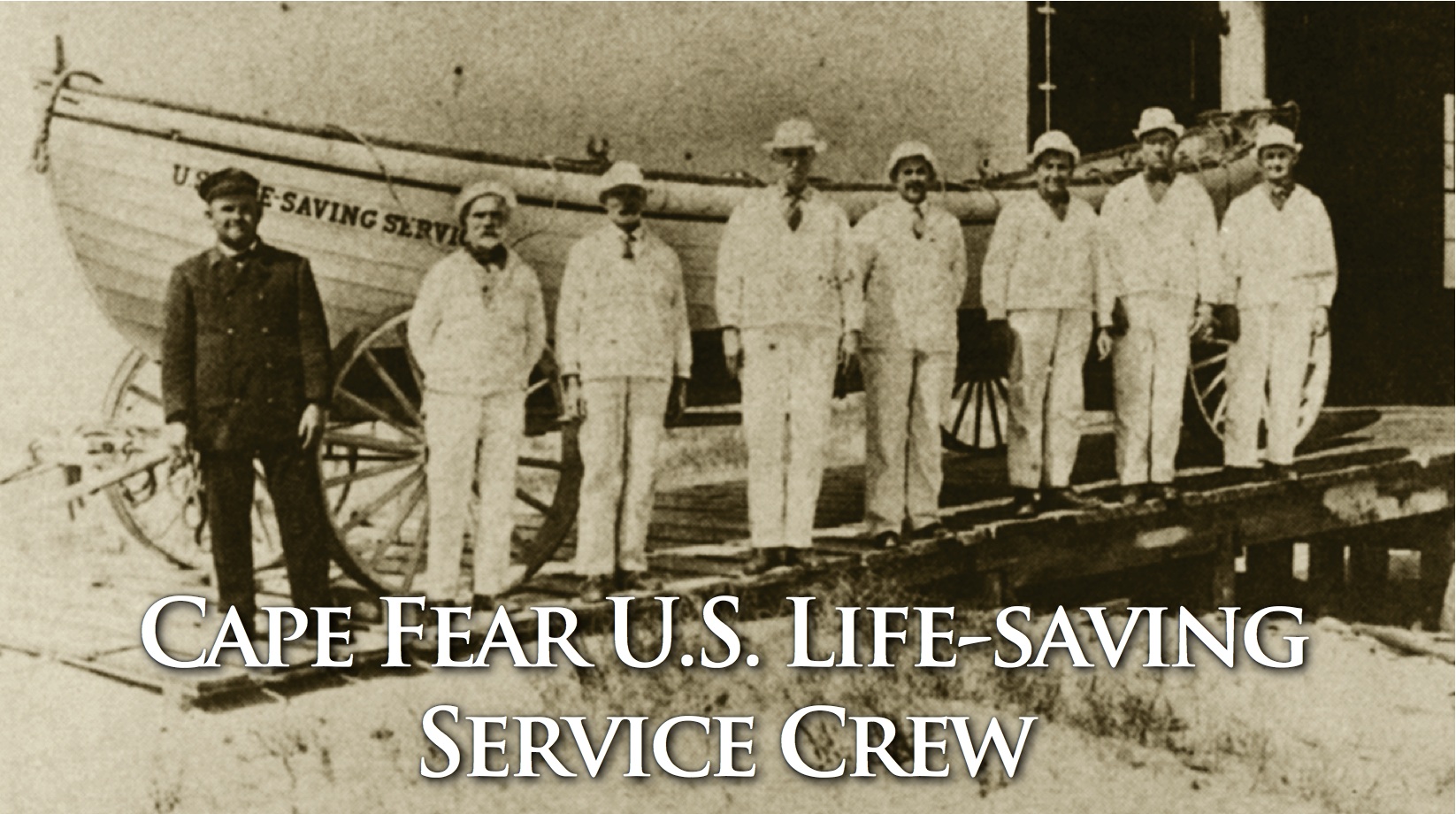

Due to the Cape Fear lifesavers’ skills, in less than 10 minutes they were able to get a line over to the wreckage and they plucked all eight crew members from the Charles C. Dame. The captain, mate and steward were white, five deck hands were black. All were barely alive.

Now there were 16 men crowded in the 27-foot-long surfboat. The boat’s gunwales were hardly above the level of the sea. Crowded as they were, Watts and his oarsmen did their utmost to control their overloaded boat, which wallowed and leapt and slewed as it surfed the waves of the shoals on its homeward bound Carolina sleigh ride. They nearly capsized more than once. A drogue, similar to a small parachute, was deployed, which slowed their progress but made the boat more manageable.

In an 1889 presentation at an international marine conference, U.S. Life-saving Service Superintendent Sumner Kimball described the art of an American station keeper steering his lifeboat in heavy seas: “His practiced hand immediately perceives any excess of weight thrown against either bow and instantly counteracts its force with his oar as instinctively and unerringly as the skilled musician presses the proper key of his instrument. He thus keeps his boat from broaching-to and avoids a threatened capsize.”

At every moment, keeper Watts’s little boat filled with water, which was eliminated by the indispensable self-bailing system although not as fast as the boat’s occupants would have preferred.

Even though they were headed downwind, the return trip still took more than four hours. Chasing them like a fiendish pack of wolves, the waves became hard to see as daylight dimmed. Sunset, even though the sun was not visible, occurred at 5:38 p.m.

The Cape Fear surfboat charged hard through the surf and in near total darkness with only the oil lamps in the station windows to guide them, they abruptly pitched up onto the beach. They were home. The time was 7:30 p.m.

Exhausted, soaked, cold, thirsty and famished, the Cape Fear crew still had to ignore their own needs in order to become hospitable hosts to the relieved but helpless and nearly naked men of the Charles C. Dame. The station’s stove was stoked, food was prepared, and clothing was provided to the destitute shipwreck survivors furnished by the Woman’s National Relief Association.

Over the next two days, all of the men rested and recuperated. Forty meals were served to the survivors, according to the station log. And on Oct. 16, the Charles C. Dame crew were taken over to Southport from where they began their long landward journey home by train.

Three days later at Baltimore, the schooner’s captain, Samuel S. Grove, sent a letter to John Watts, expressing his gratitude to the Cape Fear keeper and his surfmen for their unselfish and meritorious service: “Your heroic fight of twelve hours to reach the vessel was a super-human effort that deserves a record in the annals of the Life-Saving Service, which I, as a mariner, always regard as a sailor’s hope when shipwreck stares him in the face in storm-ridden seas along our coast. Your rescue of every man, and the safe landing of your own and my crews, was a piece of work that it delights me to pay tribute to, and the kind treatment of us while under your care requires me to double my thanks, and extend the same from my officers and crew.”

The day after “Hurricane Nine” ravaged the Carolina coast, it moved into the Great Lakes where it became known as “The Great Storm of 1893.” The storm maintained tropical force winds and rain, sinking or stranding 39 ships, and taking 54 lives.

At the end of each fiscal year, the U.S. Life-Saving Service awarded gold and silver medals for lifesaving to both the service’s employees and private citizens who performed exceptional feats of heroism in attempts to save human life.

The standards set by the service for its own men were exceedingly high. In fact, rarely and reluctantly did the U.S. Life-Saving Service bestow medals on its employees. Rarely, because it did so only when surfmen clearly risked their own lives to save those in peril on the sea; reluctantly, because even risking one’s life was considered part of the job.

In the service’s published Annual Reports, statements accompanying the names of those who were honored with medals often included the phrases: “extreme bravery,” “unflinching heroism,” “at imminent risk,” “under grave difficulties,” “great hazards” and “heroic services.”

All of these descriptions would seem to describe what keeper John Watts and his crew achieved, yet they received no medals for their rescue of the men of the Charles C. Dame during the waning hours of what today would be considered a Category 3 hurricane on Oct. 14, 1893.

Why the Cape Fear lifesavers were not recognized for their extraordinary heroism is a question that will probably always remain a mystery. One possibility may be that their Sixth District Inspector, Lt. George H. Gooding of the Revenue Cutter Service based at Elizabeth City, failed to recognize or appreciate their accomplishment.

Watts and his crew launched their surfboat in storm conditions in which no one else could. The U.S. Life-Saving Service administrators were well aware that the Oak Island crew, in responding to the same shipwreck, had failed to gain the open sea in their surfboat after two attempts.

During the same massive hurricane, the lifesaving crew at Cape Lookout, in attempting to reach the stranded British steamer Daylight had also tried but failed to launch their surfboat “on account of the violence of the sea.”

The same happened during the same storm at Chicamacomico Life-Saving Station on Hatteras Island where initial efforts to launch a boat to reach the barkentine Ravenswood were reported to be “impossible.”

Despite these well-documented failed attempts to launch surfboats, the Cape Fear crew succeeded in doing so, solely by their own daring, strength of character, and remarkable endurance.

Of course, they did not perform their unparalleled and unselfish feat of courage for recognition or rewards; they did it because it was their job. Yet, by doing so they achieved the same benchmarks by which other lifesaving crews were honored with medals.

In saving the eight men of the Charles C. Dame, John Watts and his men clearly exhibited “extreme bravery” and “unflinching heroism” at their “imminent risk” and under “grave difficulties,” facing “great hazards” while performing “heroic services.”

And for Watts and his number one surfman John E. Price, their efforts were not simply a one-time fluke. Six weeks earlier, both men had also significantly contributed to the success of Oak Island keeper Dunbar Davis’s 60-hour marathon lifesaving effort. Neither Watts, Price, nor Davis were bestowed medals for that achievement either.

There are heroes in every walk of life, even the humblest, and who well deserve the plaudits of the world, but whose names do not appear upon the scroll of fame, but whose lives are an example for others, and who have benefited the world by acts of heroism unknown beyond the limits of their own contracted surroundings.” James Sprunt, “Men of the Past,” Tales and Traditions of the Lower Cape Fear, 1896

Thirty-three North Carolina U.S. Life-Saving Service employees prior to 1920 are known to have received gold or silver life-saving medals, all of whom served on the Outer Banks.

In 1918, six lifesavers from Chicamacomico were awarded gold medals under the recently reorganized U.S. Coast Guard. In 1996, the U.S. Coast Guard awarded the Gold Life-Saving Medal posthumously to the keeper and all African-American crew of the Pea Island station for the rescue of the survivors of the wreck of the E.S. Newman on Oct. 11, 1896.

That the Cape Fear Life-Saving Station crew of 1893 and their families were denied such recognition was an unfortunate oversight on the part of the U.S. government.