In the summer of 1753, a ship transporting German immigrants set sail from Portsmouth, England, bound for the New World. Among the many who were aboard was 10-year-old Henrich Caspar Lange. Full of wonder like many his age, the boy no doubt spent as much time topside as he was allowed as the ship lurched its way out of the Solent and into the heaving gray seas and billowy mists of the English Channel.

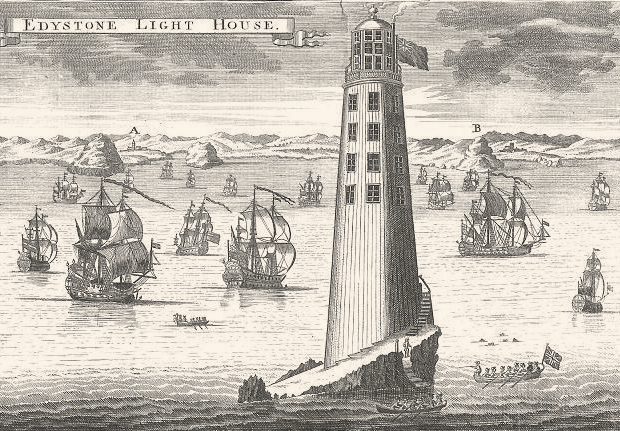

As the night passed and a crimson sky heralded their first dawn at sea, a last vestige of the Old World rose from the horizon off the ship’s starboard beam — the shape of a lighthouse standing precariously atop the wave-lashed Eddystone Rocks. At the summit of the 69-foot-tall lighthouse, a pale yellow light from 24 tallow candles glowed through the smoke smudged storm panes of the lantern. The light keepers were about to end their long, lonely watch.

Supporter Spotlight

From the deck of his ship young Lange may have pondered, how brave must a man be to serve at such a forlorn and tempestuous place? We can only imagine the impression the distant lighthouse instilled upon the heart and mind of the young boy with his life’s choices appearing ahead of him like the multitude of whitecaps on the sea.

Lange and his family — his father was a schoolmaster — settled for a time on the coast of Maine but broken promises, lack of arable land, conflicts with Native Americans, brutal winters and poverty led many of the Germans to seek a better life at the Moravian settlement in North Carolina called Bethabara, near today’s Winston-Salem. At least two migrations by ship were made from Maine’s Broad Bay to the Cape Fear River from where the families embarked on the arduous overland journey to the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

We can deduce that Lange, by then 28 years old, chose to go no farther than the Lower Cape Fear region. The native of Germany’s Westerwald hills must have found a liking for the sands, salt marshes and healthy breezes of Cape Fear. He assumed the anglicized version of his name, Henry Long, took a wife named Rebecca, and began a new occupation as a river pilot.

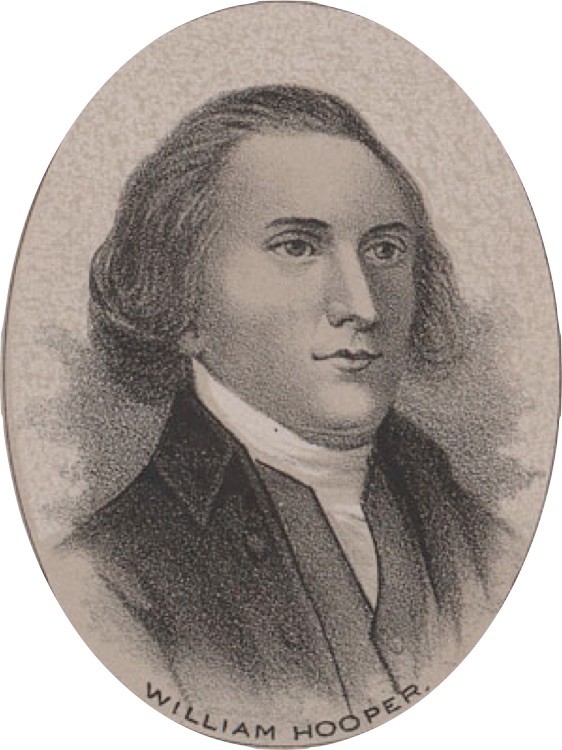

Circumstantial evidence leads us to conclude that Long had become a trusted friend of the increasingly influential Hooper family led by Harvard graduate and Wilmington attorney William Hooper. Hooper was later one of North Carolina’s three representatives to the Continental Congress and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

A few months after American Patriots and British troops clashed at Lexington and Concord in 1775, Henry and Rebecca Long welcomed their first of five children, a daughter they named Rebecca. The births of his other children suggest that during the war Long must have remained close to his home near Smithville, now Southport. Precisely how Long served his new country in rebellion against British oppression we do not know.

Supporter Spotlight

A few clues tell us that Long must have served his young nation honorably. Foremost was that in June 1794, Long was nominated by Commissioner for Navigation George Hooper, brother of William Hooper, to be the first keeper of North Carolina’s first lighthouse. It was a coveted federal position generally bestowed upon deserving war veterans.

Long was described by Hooper in Treasury Department records as the oldest pilot working the Cape Fear River but not too old to serve as a lighthouse keeper –he was just 55. George Washington approved Long’s appointment at an annual salary of $300. The amount was less than the proposed $350 but the new keeper was offered the valuable bonus of “a good house, well situated for taking fish and piloting.” As Long soon found out, however, it was not enough.

To serve as lighthouse keeper, the “not too old” pilot had to leave his mainland home with its established garden and livestock and live with his family on the isolated Bald Head Island as the only year-round residents. Strict limits on the use of the island’s resources demanded by the owner Benjamin Smith in exchange for his donation of 10 acres to establish the lighthouse there put a severe crimp in Long’s finances. Less than a year on the job, North Carolina’s only lighthouse keeper appealed to his Wilmington superintendent for more money, complaining that he was quickly accumulating “debt upon debt.”

The promise that he would be able to continue his work as a pilot to supplement his government salary was impractical. The island had no deep-water harbor where he could moor his decked sailing vessel, and the demands of lighthouse keeping afforded no time for much anything else. Even if he were able to keep his boat nearby, Long wrote, “he could not officiate as a Pilot, when the light house claims the whole of his attention.”

“All these advantages are now entirely lost to your (petitioner) by his living on an island where he has not the privilege of raising stock of any kind nor even vegetables from the proprietor of the island (Benjamin Smith) if the soil would admit thereof,” Long wrote in October 1795. “Fish and oysters are at too great a distance from the island for him to attempt to procure.” Even firewood to heat the keeper’s dwelling Long had to purchase from the mainland, even though Smith’s island was heavily timbered.

Long buttressed his appeal for a pay raise with this reminder: “Your (petitioner) therefore solicits you will consider his … services to his Country for twenty five years past and make such a representation thereof to the Commissioner of the Revenue … and counterbalance in some measure the aforesaid difficulties he labors under.” Long’s salary was raised to $333.33 and no more was heard of his financial struggles, at least in writing.

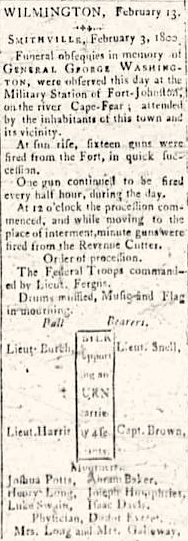

At Smithville on Feb. 3, 1800, Henry and Rebecca Long served as distinguished mourners at ceremonial funeral rites for President Washington, who had died six weeks earlier. In a noontime procession led by honorary pallbearers that began at Fort Johnston, Henry Long walked immediately behind Joshua Potts, founder of the town, as muffled drums beat a cadence and guns boomed from a revenue cutter moored in the river. Clearly, Long’s position of honor indicated that he was an esteemed citizen of the Lower Cape Fear.

When Henry Long first illuminated Cape Fear Lighthouse on Dec. 23, 1794, there were only 16 other lighthouses and not many more keepers operating in America spread along more than a thousand miles of coastline. During those early years of federal management of America’s lighthouses, keepers in remote locations like Cape Fear had no training, no instructions nor manuals to follow, and no government standards to meet other than to keep the light burning.

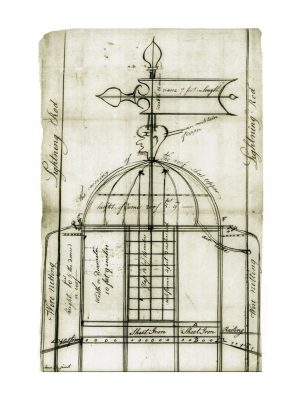

Countless times each day and night at a place nearly as lonely and tempestuous as Eddystone Rocks, Long climbed the wooden stairway carrying containers of oil, stopping to catch his breath at each of the tower’s five landings. Sixteen windows brought in abundant light, sea breezes and mosquitoes.

At dusk, inside the 10-foot-tall “birdcage” lantern at the top of the lighthouse, Long tended to a pair of oil-filled pan lamps hanging precariously by chains from the dome of the lantern. The pan lamps with 48 wicks produced a considerable amount of smoke and acrid fumes, which smudged the glass storm panes and requiring nearly constant cleaning by the keeper.

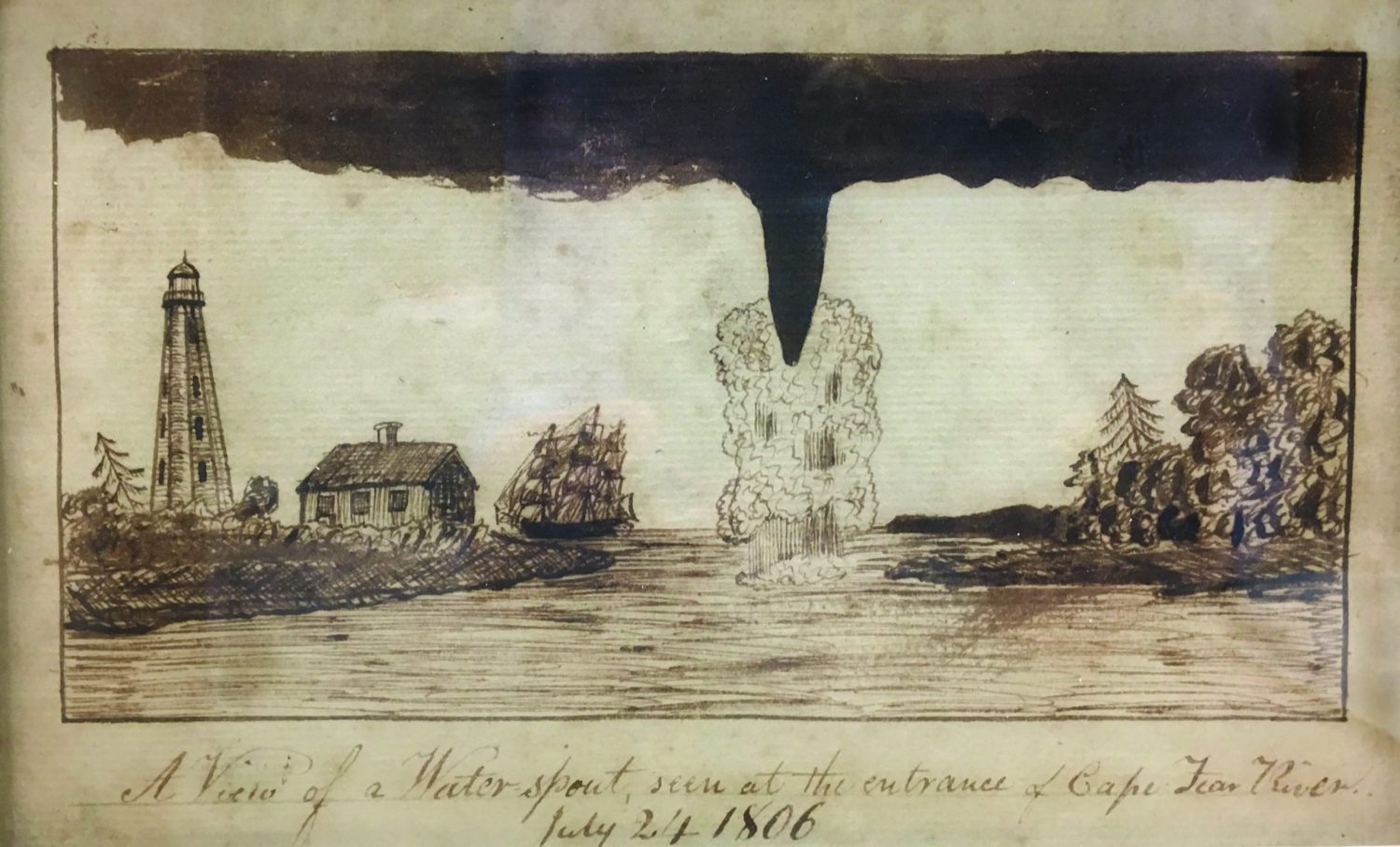

Long was expected to fulfill his nightly duty of keeping his lighthouse operating 365 days a year regardless of the weather, which was frequently frightful. On July 24, 1806, ink-black clouds presaged a nightmarish swarm of 11 waterspouts that churned the mouth of the river, barely missing the lighthouse. A few months later, a hurricane struck the Cape Fear coast that was described by the editor of the Wilmington Gazette as the “most violent and destructive storm of wind and rain ever known here.”

But even after that frightening day of waterspouts and a hurricane of utmost violence, a more horrifying tragedy struck the Cape Fear light station later that autumn.

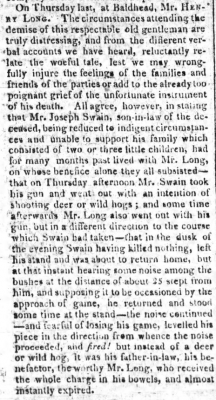

Two years earlier, Henry and Rebecca’s daughter Elizabeth suffered an untimely death, leaving her husband, Southport pilot Joseph Swain, with two young children. Swain, for reasons not known, became unable to support his family and he moved over to Bald Head to be sheltered and fed at his father-in-law’s keeper’s house. Perhaps to do his part to put food on the table, on Thursday, Oct. 16, Swain went out to hunt deer and wild hogs from a blind in the thick forest of the island.

At dusk, after spending most of the day waiting for his prey to pass his location without success, Swain was about to return home when he heard a rustling sound in bushes about 25 yards away. Fearful that he might miss an opportunity to return home to his family with something to eat, he hastily cocked his musket and fired. But instead of shooting a deer or a hog, Swain was sickened to discover that he had shot his father-in-law in the abdomen.

Henry Long died almost instantly. A notice published in the Wilmington Gazette five days later reported the tragedy: “The circumstances attending the demise of this respectable old gentleman are truly distressing.” Thus was ended the life of North Carolina’s first lighthouse keeper. Yet, his light was kept alive.

Despite the horrific tragedy, on that Thursday evening of Keeper Long’s death, and at every sundown to follow, someone continued to diligently light the lamps of the lighthouse. Each day, someone continued to lug heavy containers of oil up the six flights of steep wooden stairs to the lantern room. Throughout fair weather and foul, each and every night, someone stood the lonely watch at the top of the all-important sentinel, maintaining the wicks of the lamps and periodically wiping clear the oily haze from the window panes of the lantern.

In those days, there was no assistant keeper hired by the government to share the arduous duties of keeping a lighthouse. In those days, in the absence of the keeper, his wife did the job. And after the death of her husband, Rebecca Long heroically took over as unofficial keeper of the Cape Fear Lighthouse for the next three months.

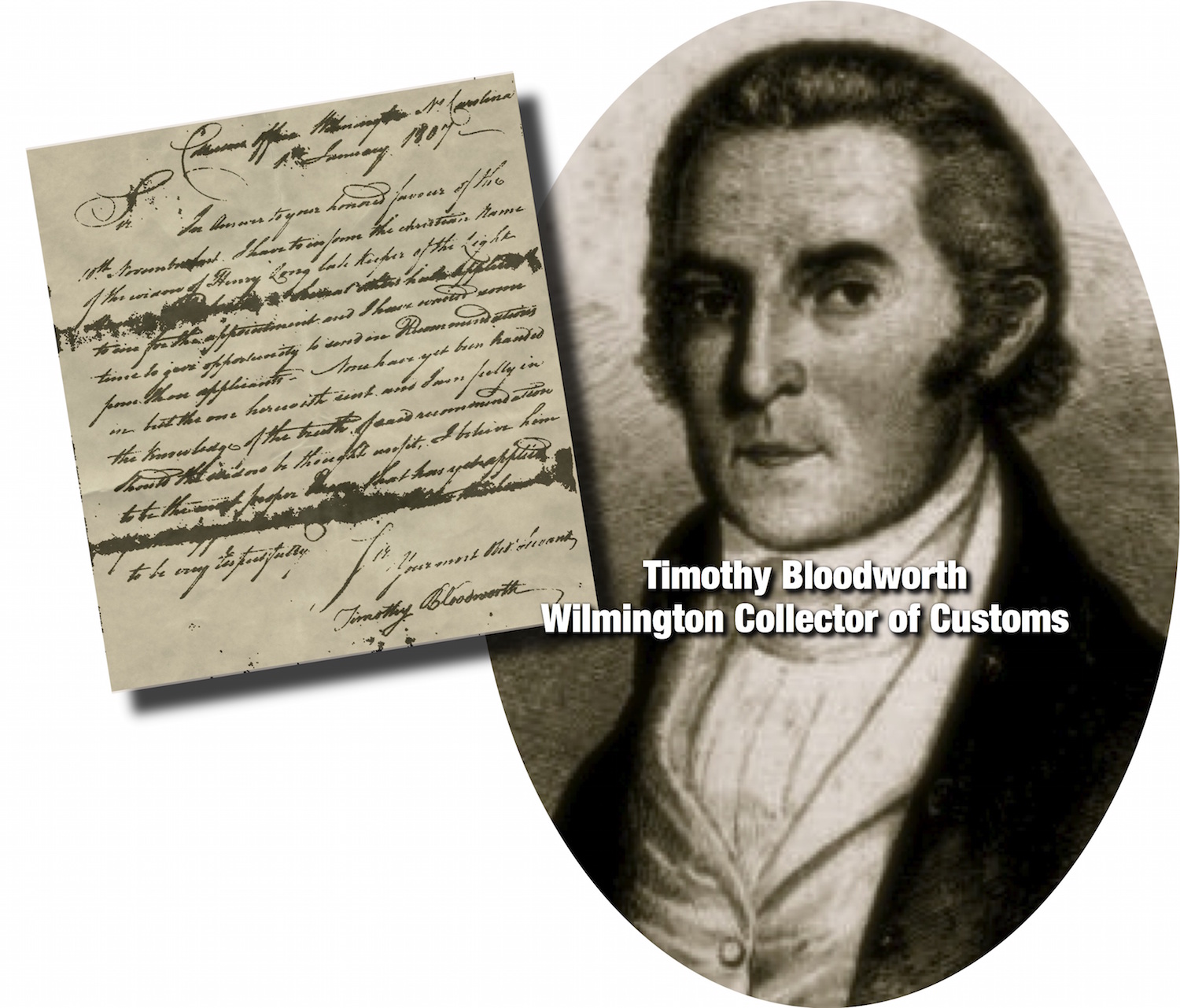

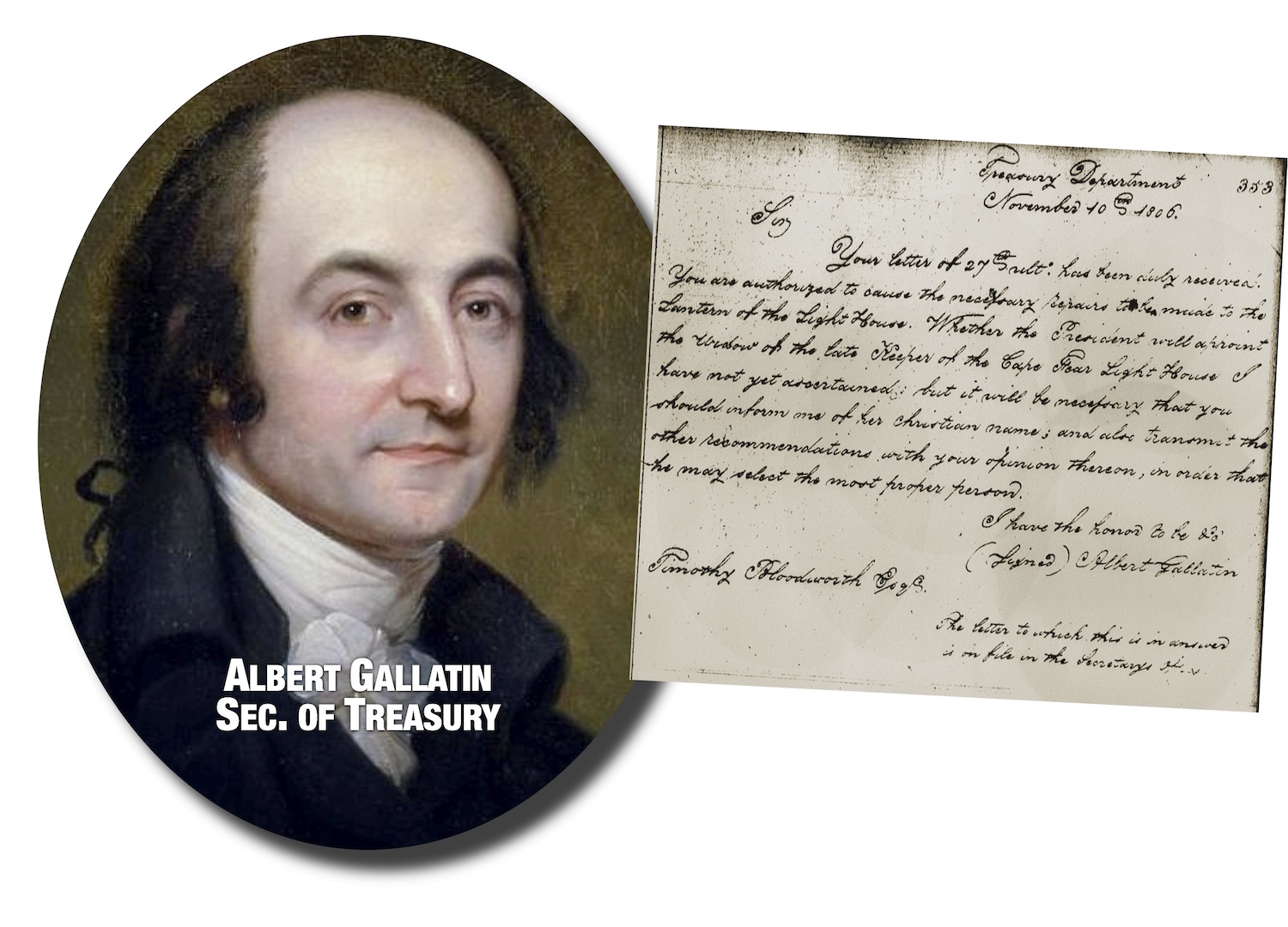

Eleven days after Keeper Long was killed and after Rebecca assumed his duties, Timothy Bloodworth, customs collector of the Wilmington port, sent a letter to the Albert Gallatin, secretary of the Treasury, proposing that the keeper’s wife be officially appointed as Cape Fear’s lighthouse keeper. Two weeks later, Gallatin replied that he was not sure that it was possible for Rebecca to replace her husband and asked Bloodworth to transmit “other recommendations with your opinion thereon, in order that he may select the most proper person.”

Bloodworth waited two months to respond to Gallatin’s request, submitting the name of Revolutionary War veteran Sedgwick Springs as his nomination in the event that the widow of the late Henry Long is deemed “inadequate to the safe keeping (of the lighthouse).”

Despite the alternative nomination of Springs for keeper, Gallatin submitted Rebecca Long’s name up the chain of command, which happened to be a very short chain — it went next to the desk of President Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s reply was categorical even if it has been misapplied by historians.

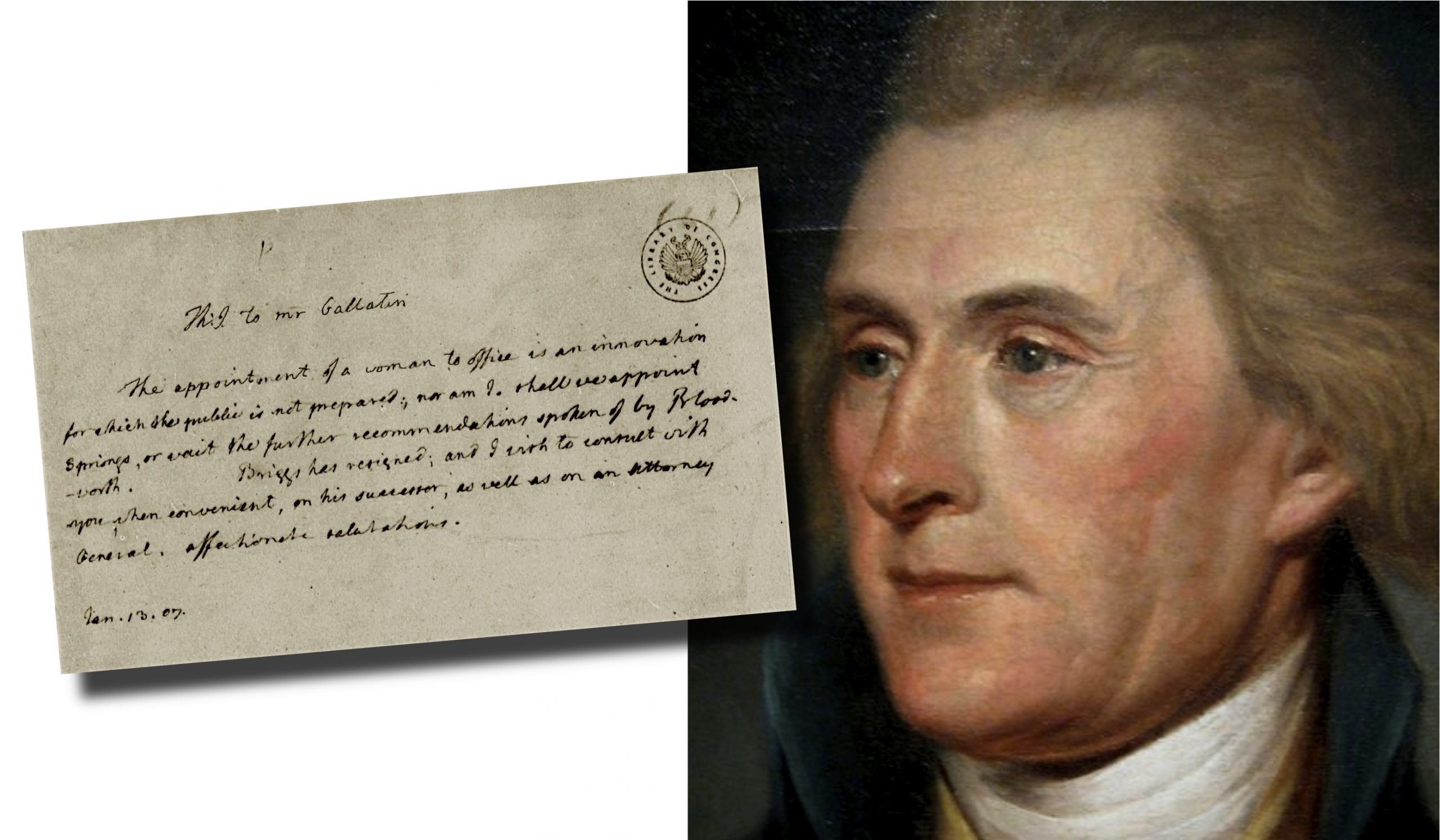

After an impressive effort of historical sleuthing, historian David E. Paterson in 2015 solved the longstanding mystery of what precipitated one of Jefferson’s better-known and often-repeated quotations that clearly revealed the Founding Father’s bias against women in public service. Jefferson’s provocative remark, made in a note from “Th. J” to Secretary Gallatin on Jan. 13, 1807, was: “The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I.”

Contrary to the commonly held assumption that Jefferson was remarking on Gallatin’s difficulty in finding qualified males to fill positions in the Treasury Department, Jefferson was responding directly to the nomination of Rebecca Long to become keeper of the Cape Fear Lighthouse, a job for which she had proved to be more than adequate and had been doing unfailingly for three long months.

Two days after receiving Jefferson’s note, Gallatin wrote to Bloodworth at Wilmington: “The President of the United States has appointed Sedgwick Springs to be the Keeper of the Cape Fear Light House, of which you will be pleased to give him notice.”

As Paterson observed, “In 1826, almost 20 years after Jefferson had rejected Rebecca Long’s nomination, President John Quincy Adams appointed the first federally employed female light-keeper.”

Ever since, dozens of women served as keepers or assistant keepers of the nation’s lighthouses. During the Early Republic period, women were estimated to comprise 5% of principal lighthouse keepers. Some performed feats of heroism.

Ida Lewis, keeper of the Lime Rock Lighthouse in Rhode Island, was awarded a gold medal in 1881 “for saving lives at her imminent peril.” Had Thomas Jefferson been as enlightened as popular culture sometimes likes to remember him, Cape Fear’s Rebecca Long might have become America’s first woman lighthouse keeper.

Rebecca moved her family across the river to Smithville. One can imagine that she might have occasionally glanced across the river at the Cape Fear Lighthouse at sundown to make sure that it was lighted on time. Or, perhaps, she never looked back there again. She died on May 2, 1815. By then, the lighthouse was gone, too.