In 1942, one of the most horrific and intense battles of World War II raged off the coast of North Carolina.

It was the Battle of the Atlantic, a battlefield that encompassed the Atlantic Ocean from North America to Europe.

Sponsor Spotlight

Dare County was still sparsely populated in 1941 when the United States entered the war. There were around 6,500 residents scattered from Caffey’s Inlet north of Duck to Hatteras Village. Manteo, the county seat, boasted a population of 550 and that was the largest town in the county.

It was an area in transition. A wooden bridge connecting Kitty Hawk with the Currituck mainland had been completed in 1930, making the Outer Banks from Hatteras north accessible to anyone with a car. The first beach cottages were built in Kitty Hawk in the 1930s.

The transition was slow, though, and most Outer Banks families still earned their living as they had for generations — fishing, hunting, working as a guide from time to time and subsistence farming.

North Carolina and the Outer Banks were on the front line of a nightmare battle for control of the sea.

Sponsor Spotlight

For older Dare County residents, even after almost 80 years the memories are still there, the horrific explosion that shook the house in Duck; the military guard posts and the exotic foods that would wash up on the beach.

In the first four months of 1942, German U-boats ravaged the shipping lanes off North Carolina, sinking almost 40 ships during that period.

It is an often overlooked piece of American history now, and even at the time it was occurring, very few people knew about it.

Stanley Beacham is 84 and works occasionally at the Outer Banks Visitors Bureau Welcome Center on Roanoke Island. At times he will mention the war to visitors.

“People would come in and people they say, ‘We never heard of war on the Outer Banks’,” he said in an interview.

“Roosevelt did not intend you to. He did not want to alarm the nation,” he explained. “We were very isolated. We did not even know properly we were part of North Carolina we were so isolated,” he added.

The isolation, though, did not keep the war from the doorstep of the Outer Banks.

Living at Caffey’s Inlet on the north end of Duck at the time, Beacham can still recall in detail what it was like.

“The conversation went everyday about the German submarines. They torpedoed ships day and night. The one that I remember the most, I was almost 7 years old and my mama peeled me an apple. I was sitting on the porch eating it. Our house was 30 feet from the sound and across the sand hills from the ocean. They torpedoed a ship right off Caffey’s Inlet and it shook the earth. I screamed and ran and Mama came out to get me,” he recalled.

Norma Perry was living in Duck and she has a similar memory.

“I think I was about second grade,” she said. “We had a big radio that picked up shortwave and you could do regular radio. And every Saturday night Mom and Daddy would always listen to the Grand Ole Opry … I wanted to stay up that night, because I wanted to listen to some music. But really I didn’t want to go to bed. All of a sudden it sounded like a great big thunderstorm coming up. Big booms. Mom and Daddy flew out the back door. It was just a short distance before you came to the sand hills. The water was on fire all around it. Mama would cry for just about a week.”

For Beacham, who grew up in a large family that often didn’t have much, there were some unexpected rewards.

“Every day we could go on the beach after the Coast Guard … cleared and checked for bodies, if there was anything washed ashore like lemons, grapefruit. We could pick it up,” he said.

“I remember one particular day, we walked over with my two older brothers, a stalk of bananas had washed ashore. They were green as a gourd, and my brothers picked them up and took home. Mama … hung them up in the pantry and they ripened. I can honestly tell you, the first banana I ever ate washed in on the beach. It was a treat.”

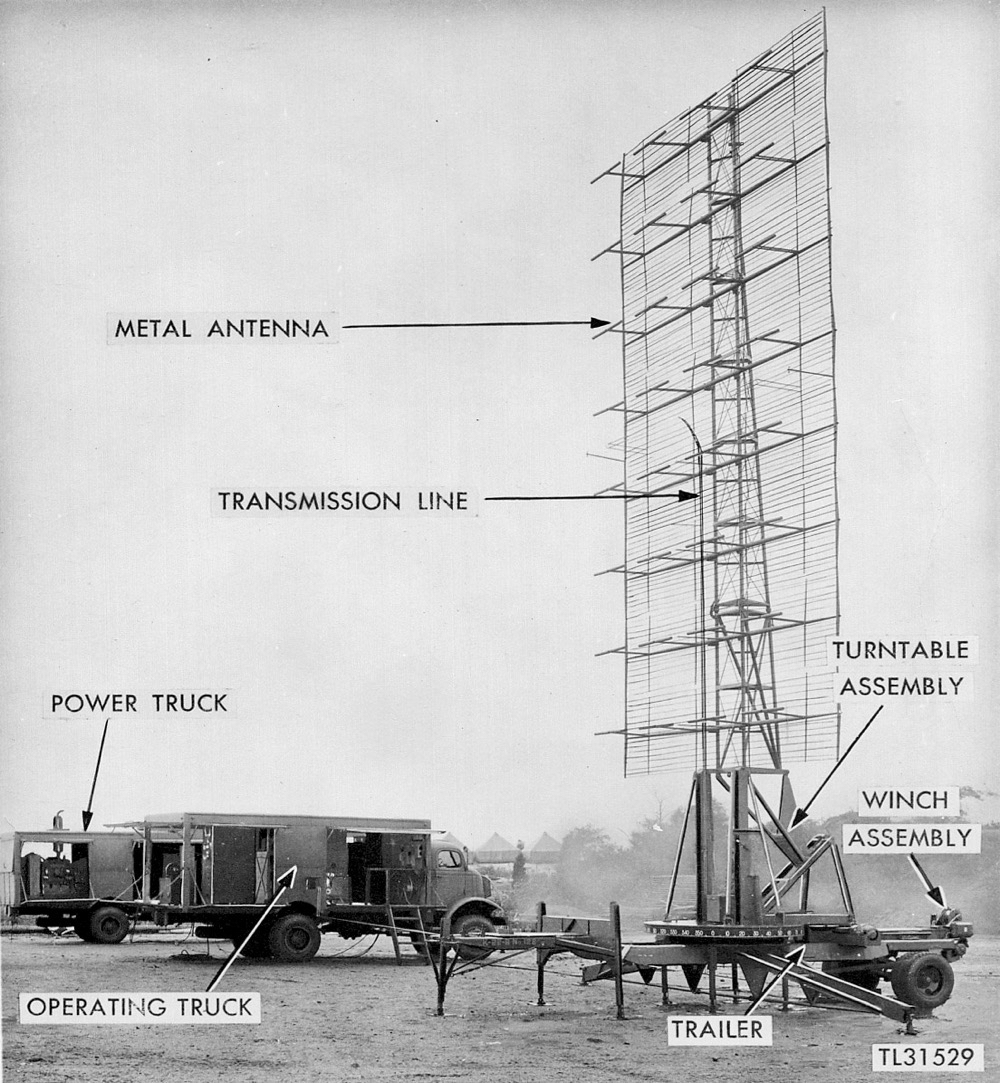

As the U-boat attacks intensified, the government moved quickly establishing an Army radar installation and observation tower in Kitty Hawk early in 1942. Today the location is the Holy Redeemer Catholic Church, but to the residents who lived in the village in World War II, it’s still Army Camp Hill.

The Army and the war brought changes to the way things were done in the village. Norma’s husband Cliff remembers the blackouts and how they were enforced.

“If you had lights on … they couldn’t shine outside of your house. They had certain people come through the neighborhood … and check and see if they could see light. If they could see a light in your windows they could come to your house and tell you,” he said. “It wasn’t any kin to me, Edgar Perry was the game warden at the time and I think he was in charge of that part of it.”

He recalls the Army would come to the village looking for information, but there was were sometimes a treat with their visits.

“The Army people would drive through the village and stop and talk to people wanting to know if they had seen any strangers in the village. If they had some excess of fruit, apricots seemed like one of the things, they would pass out some things to the people,” he said.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Kitty Hawk was a small village with a population of 250 to 300. There were two paved roads, what is now N.C. 12, the Beach Road, and a small portion of Kitty Hawk Road from its intersection with the Beach Road west for about one mile.

Kitty Hawk Road ran through the middle of the Army base, and something as simple as going to the store changed.

Cliff remembers being stopped as the family was on the way to Anderson’s Store on the Beach Road at the north end of town.

“If you went over on the Beach to get groceries, up at Andersons, they stopped you going and coming,” he said.

It wasn’t just the occasional car taking a trip up to Anderson’s Store. Kitty Hawk School was the K-12 school for the area, and Norma Perry recalls what it was like passing through the guard gate.

“They would stop the school bus and one guard would come on the bus and look across the heads and the other one would stand on the ground and stick his head in so he was looking under the seats at the feet,” she said. “You knew there were going to do it but it was still just a little bit scary.

Army Camp Hill wasn’t the only military location with a guardhouse. The site where the Duck Pier, the Field Research Facility at Duck, is located was a bombing range in World War II.

With his father and brother in the Coast Guard and another brother in the Navy, Beacham’s mother moved the family down to Kitty Hawk. From time to time, though, he would visit relatives in Caffey’s Inlet.

“My brothers would drive up there and I would ride with them. When you got to the range, you would stop and tell the guard ‘I want to pass through.’ They would radio the planes that were making a big circle,” he said. “Their replay was, ‘Cease fire. Hold your pattern.’ They would hold the pattern. I would wonder, ‘My God. I hope they heard them.’ That’s the way we got through the bombing range.”

The changes began before the United States entered the war as the nation prepared for conflict. The Navy in Norfolk was gearing up and they paid well and Shelby Hines recalled why his father moved the family to Norfolk before the war.

“He left here in December ’39. Here he was making $.25 an hour. Up there, they were getting ready of war, and they were paying $1 an hour. There were like 50 families from around here that went up there,” he said.

Cliff Perry remembers that as well.

“Most of the people left the area and went to Norfolk to work in the shipyards,” he said.

The effect on everyday life during World War II was felt throughout Dare County. Perhaps no place in the was that impact felt as profoundly as Manteo and Roanoke Island.

As the war effort grew, the need for ships grew with it. The large shipyards of the East Coast were working overtime producing Liberty ships by the thousands and fighting ships for the Navy.

But the armed services needed wooden ships as well—for minesweeping, landing craft and lifeboats, and Dare County with its rich history of boatbuilding was ideally positioned to take advantage of that.

It helped that Congressmen Herbert Bonner, who served in the House of Representatives from 1940 until his death in 1965, was a powerful figure in Washington and that Bruce Etheridge, director of the North Carolina Department of Conservation and Development, was a former business owner in Manteo with deep roots in the area.

On Feb. 6, 1941, the Manteo Boat Building Corp. was formed. Within a week they had a contract to build 20, 14-foot sailing dinghies for the Naval Academy.

The company was remarkably undercapitalized. In his article, Wooden Ship Construction in North Carolina in World War II written for The North Carolina Historical Review, William Still noted,” According to several of the company’s former officers and members of its board of directors, the firm received a contract even though it had no operating capital at all.”

What it did have, according to the information Stines found, was an acknowledged expertise in boatbuilding, something the naval officer in who recommended Manteo Boat Building for the contract noted.

“It has been organized and is to be administered by men who more or less their entire lives either have built boats or have been associated with boat building…For this fact and the fact that adequate power and hand tools are already on hand, the inspecting personnel believe that the Manteo Boat Building Corporation is capable of meeting all terms of the contract,” he wrote.

It was the beginning of a lucrative and productive time; skilled workers were in demand. The company built a number of landing craft for the military, as well as the dinghies They also built 13, 105-foot patrol and number of 63foot and 85-foot crash boats—watercraft specifically designed for open water rescue.

The need for skilled workers reached all the way to Duck and Norma Perry’s father, Charlie Spruill, answered the call.

“There were some people over in Manteo who had worked with him before and they knew he was capable of doing it. …They had a just little place where they were building these ships and landing craft and a few little tiny boats. Mostly landing craft,” she said.

The war brought other changes to Manteo as well, perhaps nothing as significant as what is now the Dare County Regional Airport.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the Navy already had plans to build an auxiliary air station on the Outer Banks. The airfield though was still in its planning stage according to Dare County Airport Museum information.

On Roanoke Island, however, Dare County Commissioners had authorized funding for an airport and construction was underway on the north end of Roanoke Island. The Navy opted to finish the project.

Fifteen months later on March 3, 1943, Naval Auxiliary Air Station or NAAS Manteo was officially commissioned.

Initially it was used as an advanced training base for carrier based and Marine fighter pilots — the F6F Hellcats, SB2C Helldivers, TBF Avengers and F4U Corsairs among others.

In April of 1943, Corsair squadron VF-17, the Jolly Rogers, arrived in Manteo to complete their training before they were deployed to the Pacific. The Jolly Rogers went on to become, according to the Naval Aviation Museum, the “greatest Navy fighter squadron in history.”

In that squadron was Lt. Ray Beacham of Kitty Hawk.

“He was my cousin,” Stanley Beacham said. “His grandmother raised him because his momma died when he was 3 years old.”

Ray Beacham’s house was close to where Stanley Beacham’s home was in Kitty Hawk and he remembers what Ray would do to let his grandmother he was alright.

“He would fly over her house in his fighter plane and he would fly over her house till grandmamma came out to wave at him. One time he was so low down, she crawled under the porch,” he said. “Kitty Hawk Kid they called him.”

In addition to the advanced training, the Navy and Coast Guard used the airport for their submarine patrols.

The military ceased operations from Manteo in December 1945 and turned the facility over to Dare County in 1947.

Most of the reminders of the impact on World War II are gone now. Occasionally relics of the war will wash up on the beach. The Navy placed some 2,400 mines in the waters off the coast and never did retrieve all of them. From time to time one will wash up on shore.

In Duck, at the Corps of Engineers Field Research Facility there are warning sign posted. As a 1985 paper on the Duck Pier noted, “The site had been used previously by the Navy as a practice bombing range, and occasionally practice rounds of ammunition are found on the property.”

Other than that, though, there isn’t much to note one of the most horrific battlefields of World War II.

At sea there is an effort to preserve the past. The Monitor National Marine Sanctuary has been recording the toll the Battle for the Atlantic cost in the waters of North Carolina.