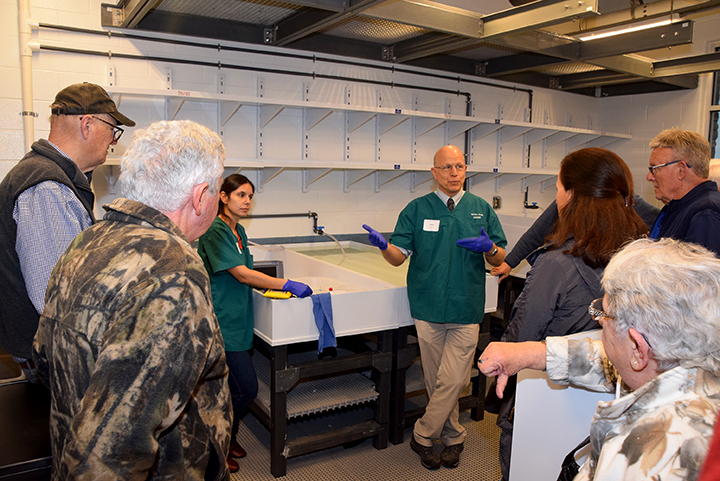

MOREHEAD CITY – Seawater from Bogue Sound runs through pipes and a filtration system, making its way up into an elevated storage tank before being circulated at a rate of up to 350,000 gallons per day throughout the newly renovated and specialized laboratories at the University of North Carolina Institute of Marine Sciences.

“And as a result, we’re one of the few facilities, certainly the only facility at Carolina, that has running seawater and can maintain medium-sized to large-sized extended studies with fisheries and animals,” Rick Luettich, the institute’s director for the past 16 years, said last week during a ribbon cutting and tour of the refurbished labs.

Supporter Spotlight

But the saltwater environment that makes possible the numerous types of coastal research here also creates maintenance challenges that had taken a toll on the 4,100-square-foot facility built in the early 1990s, Luettich explained March 4 to about 50 invited UNC alums and dignitaries. Guests included UNC Vice Chancellor for Research Terry Magnuson, Rep. Pat McElraft, representatives for Gov. Roy Cooper and Congressman Greg Murphy, R-N.C., and Beaufort Mayor Rett Newton.

Magnuson, speaking during the event, noted that the institute is the university’s sole field site dedicated to marine science research and the coastal ecosystem since 1947, when a permanent campus was built.

“And why would we build it here? Because obviously we do things here that we could never do up in Chapel Hill. So, it is the ideal place to study ecology and conservation, restoration of cultural resources and developing and applying new technologies,” he said.

“It is the ideal place to study ecology and conservation, restoration of cultural resources and developing and applying new technologies.”

Terry Magnuson, Vice Chancellor for Research, University of North Carolina

The institute’s history here goes back much further. UNC started having classes and programs in Carteret County in 1894, but the site’s value really started becoming clear once UNC established a more permanent presence in Morehead City.

“In the 1950s, we did a lot of work in — and really we were founded to help the state work and develop commercial fishing,” Luettich said. “In the 1950s, research done here at the lab led to the discovery of the brown shrimp industry, which is a major shrimping industry for our state and in fact in the Southeast.”

Supporter Spotlight

Luettich said that in the 1960s, the institute expanded to a broader marine science program and, in the following decade, launched what has become a well-known shark research program.

“We have one of the longest data sets that chronicle actually the crash of the apex predators, the large shark species that are off our coast, in the late 20th century and their rebound in the early 21st century, largely due to management actions that we helped discover and helped promote in the ’80s and ’90s,” Luettich said.

Distinguished Professor Emeritus Charles “Pete” Peterson conducted research here that helped boost the state’s scallop industry, Luettich said, and Kenan Distinguished Professor Hans Paerl’s work examining algal blooms and their relationship to dead zones and fish kills in the Neuse River estuary and the Albemarle and Pamlico sounds in recent decades has focused much of the institute’s fisheries work on water quality and coastal hazards.

Magnuson, in his remarks, called the lab a training ground for students to learn to be creative and help the university and the state advance fisheries science, water quality, ecosystems, coastal resilience and human health.

“And it’s very important because it provides expertise to agencies across the state, also to industry, and it helps to inform public policy,” he said.

Magnuson said the renovated facilities would also help expand what faculty and trainees can do here and attract researchers from other institutions.

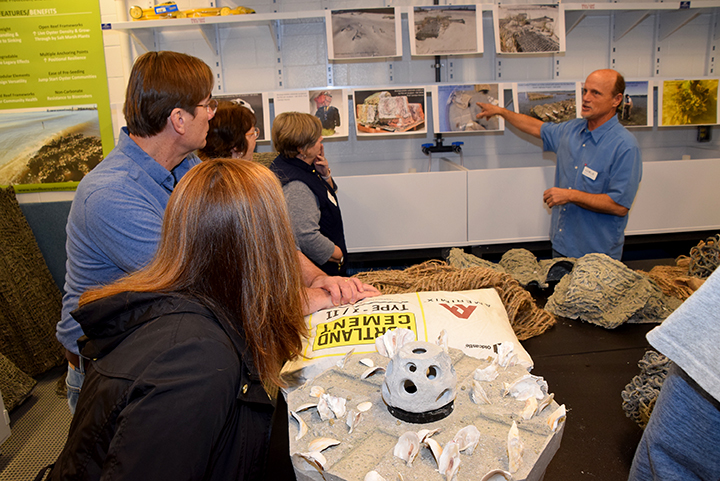

Collaboration with other universities is already happening here. The single-story building features six labs on the sound side and four on the side that faces Arendell Street. Eight of the labs are reserved for UNC’s use and the other two are for researchers from N.C. State University, including Dr. Craig Harms, professor in NCSU’s Department of Clinical Sciences.

The $795,000 renovation brings the institute’s 10 wet labs up to the latest standards in terms of safety, longevity, accessibility and marine animal welfare. Money for the upgrade came from the UNC Chapel Hill Division of Comparative Medicine, formerly known as the Division of Animal Laboratory Medicine.

Floors that could previously pose a hazard when wet have been replaced with a grate system that allows spills to safely drain away. Lab spaces are now capable of being entirely hosed down as needed or reconfigured to allow for flexibility, different experiments and to meet different researchers’ various needs.

Features prone to rapid decay in the moist, salty air have been replaced with new equipment made of specialized materials designed to better resist corrosion.

The facility has been brought up to the latest Americans with Disabilities Act standards with wheelchair accessibility possible in all parts of the lab.

And marine life studied here are cared for under the semiannual review of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, a group of veterinarians, scientists, ethicists and others that is responsible for oversight of the proper care and use of laboratory animals.

“This really has brought our wet lab facilities up to par with that of the state aquarium system’s in keeping animals in top-notch conditions,” Kerry Irish, who handles communications and outreach for the institute, told Coastal Review Online Monday.

Irish described the work done at the institute as applied science with tangible benefits for the state.

“We’re doing stuff here that yields real results for the people who live at the coast,” she said, adding that students at the institute are regularly recognized for their contributions to the state’s fisheries and ecosystems management in ways that improve coastal residents’ lives.

“The majority of work we do here at the coast pays dividends back to the people who live here,” she said. “The new facility helps us do work better and we, as scientists, are part of the community.”

Because of the nature of the work that happens in the building, there’s a lot of use, Irish said.

“Three decades of hard use on the facility really took its toll — it was mucky, dirty, salty and corrosive. It had given us good use, but it was time to fix it up.”