ROANOKE ISLAND — On the same verdant land where newly freed slaves once found refuge, a small group gathered at Fort Raleigh National Historic Site to commemorate the shameful day 400 years ago when African slaves were first brought by the English to the shores of Virginia.

Along with other national parks nationwide, the mid-afternoon remembrance on Sunday started at 3 p.m. with four, one-minute readings, each enunciated by a single bell tone to mark a century.

Supporter Spotlight

“We still live with the very tangible remnants of slavery and segregation today that started on that day,” said Michael Zatarga, a park ranger and interpreter at Fort Raleigh, speaking prior to the readings. “The erasure of an uncomfortable past is not just. Only through conversations around these remnants, we can help our nation grow and begin to heal.”

It was there around Fort Raleigh, where about 30 people sitting in folding chairs outside the visitor center listened quietly to the speakers, that escaped slaves came to reclaim their humanity. But until about 20 years ago, that history was overshadowed by the history of early English settlements – most notably the infamous Lost Colony – and Civil War battles.

Brief and simple, the service had an unforced somberness. Park ranger Byron Parker used a small ordinary bell to strike before readings, but its blunt ring was suitably doleful. The moment of silence at the end united Outer Bankers with the nation in contemplation of the searing impact of that fateful day in 1619.

“Just about every black person here is related to someone who is a descendant of the Freedmen’s Colony.”

Virginia Tillett

Communities on the Outer Banks, especially Hatteras and Roanoke Island, were some of the first to take in large numbers of freed or escaped slaves in the early days of the Civil War.

Of the four readers, quoting from historic records, two were descendants of the Freedmen’s Colony, a vibrant community of free black men, women and children on Roanoke Island from 1862-1867. Established by the Union after black refugees began flooding onto the island, it was the first colony of freed slaves that was set up as a town with a goal of becoming permanent, with churches, stores and, most importantly, schools.

Supporter Spotlight

The community had some measure of success, but it was disbanded after the war when President Andrew Johnson returned confiscated property to its previous owners. Despite efforts from historians and archaeologists, not one trace has been found, other than historic documents, of the settlement that at its height had as many as 3,500 residents.

Still, black people had lived on Roanoke Island before the war, and many stayed after the war. Indeed, about a decade after the colony’s demise, a group of former Freedmen’s colonists combined resources and purchased 200 acres, subdividing it into an area they called California.

“Just about every black person here is related to someone who is a descendant of the Freedmen’s Colony,” one reader, Virginia Tillett, a 78-year-old retired educator and Manteo native, said after the service.

Many members of the small black community today live in that same mid-Manteo neighborhood where they have for generations, but the Freedmen’s Colony was known to have been on the north end of Roanoke Island, including the part where the national park is now. A large tract of land where the county airport is today had also been owned after the Civil War by a black family.

Tillett, whose ancestors were Simmonses and Ashbys, had served a total of more than 30 years on the Dare County Board of Education and the Dare County Board of Commissioners and has worked through the years to preserve the history of the colony in which she and so much of her community have their roots.

“In 1861, the nation struggling half free, half slave descended into civil war,” said Zatarga, elaborating on a reading given by park ranger Adonis Osekre. “For North Carolina, the war came to its shores early with Union victories at Hatteras and Roanoke Island. Soon enslaved people flooded the Union outposts seeking safety, but what to do with the refugees? The answer came in 1863.”

According to 1860 census, Osekre said, there were 3,953,760 slaves in the U.S, 331,059 in North Carolina, 2,524 in Currituck County, which then encompassed Dare County, and 173 on Roanoke Island.

“From former army barracks to a small city, African-Americans formed an environment they could call their own,” Zatarga said after a reading by Beulah Ashby, 66, also a descendant of the colony. “With churches and schools they found importance and self-sufficiency. From here they learned the power of the written word. From here they contributed to keeping themselves free.”

Ashby, who works for the Dare County Water Department, is descended from Spencers, Scarboroughs and Collinses, all prominent Manteo family names to this day.

But as Ashby and Tillett noted after the commemoration, not much was known – or even mentioned – about the Freedmen’s Colony until 2001, when author Patricia Click published “Time Full of Trial: The Roanoke Island Freedmen’s Colony, 1862-1867.”

Click explains in the preface of the book that then-Manteo Mayor John Wilson IV asked her in 1981 to write the history of the colony, shortly after her arrival fresh from graduate school when she worked as a historian-in-residence for the town. She soon discovered that the history was far more involved and profound than she had realized, and it ultimately took two decades to complete the book.

“The story of the Roanoke Island’s freedmen’s colony (sic) is one of national significance,” she wrote in her opening sentence, “yet few people know anything about it.”

In fact, Click’s book was the first detailed account of the colony, despite its importance in the history of African slavery, the Civil War, Emancipation and Reconstruction. Tillett’s stepdaughter, Arvilla Tillett Bowser, later wrote a second book, “Roanoke Island: The Forgotten Colony,” which followed the families from the beginning of the colony to the contemporary community.

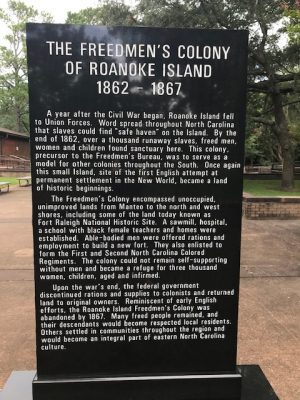

Fort Raleigh National Historic Site, which was established in 1941, had no marker commemorating the Freedmen’s Colony until 2001.

“This colony, precursor to the Freedmen’s Bureau, was to serve as a model for other colonies through the South,” read the engraved words on the marker. “Once again, this small island, site of the first attempt at permanent settlement in the New World, became a land of historic beginnings.”