FAYETTEVILLE – Chemours officials announced this week that the company had submitted to the state Department of Environmental Quality the Cape Fear River PFAS Loading Reduction Plan, which offers proposals to reduce levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances from the Fayetteville Works site reaching the Cape Fear River.

“Over the past few days, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality has received numerous reports from Chemours as they pertain to the consent order signed in February. Some exceed 1,500 pages. These reports are under review by DEQ staff,” Laura J. Leonard, public information officer for the state Division of Waste Management, told Coastal Review Online.

Supporter Spotlight

The consent order between Chemours, NCDEQ and Cape Fear River Watch “requires Chemours to address all PFAS sources of at the Fayetteville Works facility to prevent further impacts to air, soil, groundwater and surface waters, according to NCDEQ. The Cape Fear River PFAS Loading Reduction Plan was required to be submitted within six months of the consent order. The full consent order and GenX investigation timeline can be found on DEQ’s website.

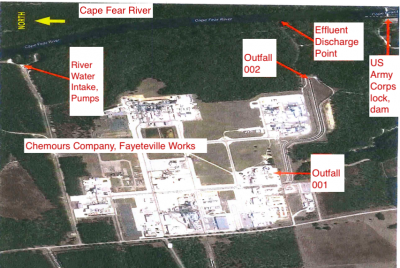

The plan included new information that is to be used to determine the best approach to long-term mitigation of PFAS loading to improve water quality in the river and outlined seven recommended actions Chemours intends to take to reduce the amount of PFAS that enters the river near the Fayetteville facility through various pathways, including site outfalls, seeps and groundwater sources. Details of the plan can be found on Chemours’ website.

Brian Long, Fayetteville plant manager, said in a statement that the first phase of action was to substantially reduce current emissions, “and we’ve done that. We have already achieved over a 95% decrease of C3 dimer acid in the river, a 92% reduction in air emissions of PFAS constituents, and we’ll soon be controlling 99% of air emissions when our Emissions Control Facility is completed at the end of this year.”

Long said that after addressing active emissions, which contribute the greatest amount of PFAS, “you can really start to delve into the historic issues, which still impact the river but are a smaller contributor.”

Once comprehensive historic environmental contaminants data is collected, that information can be used to determine the full impact on soil and ground water and the most effective remediation approach can be developed, Chemours said.