The story has been updated.

BEAUFORT – The North Carolina Department of Transportation has in the works a short-term fix for erosion at the Hatteras ferry terminal on Ocracoke Island but is also working with the National Park Service on a long-term solution.

Supporter Spotlight

During its meeting at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Beaufort Lab on Pivers Island Wednesday, the Coastal Resources Commission granted NCDOT a variance to build a temporary erosion control structure that exceeds the permitted height and will stack the larger than permitted sandbags perpendicular as well as the permitted parallel at the ferry terminal within the Cape Hatteras National Seashore.

The temporary sandbag structure will be built adjacent to a bulkhead, which construction is expected to begin on this week, as authorized June 21 by Division of Coastal Management.

Ocracoke can only be reached by ferries that leave from Cedar Island in Carteret County, Swan Quarter in Hyde County and the Hatteras Inlet ferry, which is the most used by travelers and serves as an evacuation route.

Christine Goebel, assistant general counsel with the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality Office of General Counsel, told the commission that shoreline erosion, dune loss, frequent overwash, flooding damage from frequent storms and the shifting of Hatteras Inlet have been particularly severe at the Hatteras ferry terminal.

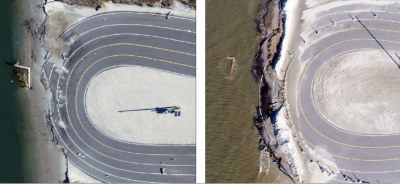

During summer 2017, spring 2018 and after Hurricane Florence in fall 2018, NCDOT put in place measures to slow erosion at the hairpin turn. But with the erosion rate of 7 to 15 feet per month this past winter, the terminal site lost more than 70 feet of shoreline in the last year to erosion, according to the variance request.

Supporter Spotlight

As a result of the erosion, the ferry boarding lanes at the hairpin turn disintegrated and have been closed since March because of safety concerns, Goebel said. An emergency declaration was issued that month because of the rapid erosion.

“If continued erosion were to cause the existing bulkhead to fail at the ferry basin, the entire ferry basin would be impacted, causing unsafe conditions for the loading and unloading of the traveling public,” Goebel said.

Tim Hass, NCDOT Ferry Division communications officer, told Coastal Review Online that NCDOT had completed beach renourishment when dredging the adjacent ferry channel and basin twice during the last eight years. In 2018, sandbags were put in place to save the hairpin turn from becoming compromised. Sand was also placed on top of the sandbags and a dune was created.

However, the sandbags failed to protect the stacking lanes and the ferry basin. By spring, asphalt had started crumble.

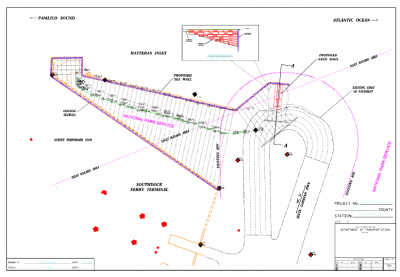

NCDOT submitted June 13 a request to Division of Coastal Management for an emergency stabilization project that included about 1,000 feet of sheet pile bulkhead in front of an existing steel sheet pile bulkhead, and sandbags as a temporary structure intended to protect the ferry terminal from further erosion, according to the variance request.

The division issued June 21 an emergency major modification to Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, permit No. 224-87, giving the go-ahead for NCDOT to install the sheet pile bulkhead as part of the proposed project but denied the request to build the proposed sandbag structure partially in the inlet hazard area.

Hass said that with the Army Corps of Engineers issuing July 16 the last permit needed for the project, NCDOT can proceed with the bulkhead work, which was expected to get underway this week.

The temporary sandbags are to be placed at the end of the sheet pile wall to protect it and prevent erosion caused by easterly winds until the groin project is complete.

Hass said that if the sandbags area not installed, “there would be no way to stabilize the area between the sheet pile wall and the existing roadway; therefore, allowing for additional erosion to occur.”

NCDOT filed a variance request June 27 for the proposed sandbag structure, and asked to have the variance expedited and reviewed during the commission’s meeting last week.

The size of the sandbags and height of the stacks, which would be perpendicular and parallel to the shoreline to act as a temporary groin, aren’t allowed under the rules for temporary erosion control structures. The permit allows only for sandbags to be placed parallel to the shoreline without exceeding 6 feet in height or 20 feet in width, according to the variance request.

The project is expected to use about 40 sandbags in three different sizes: 2 feet by 5 feet by 15 inches; 3 feet by 3 feet; and 4 feet by 4 feet. The sandbag wall would likely be 50 feet long and 15 feet wide, tapering as it rises to a maximum height of 15 feet.

Hass said that the specified sandbags were chosen because they are sizes the department already has in its inventory. The proposed sandbags’ orientation was designed to provide the most stability.

The structure is to be placed in the water and be higher than the water depth. The water is predicted to be 14 to 15 feet deep by the time construction begins, which should be in the early fall and will take about a month to complete.

Mollie Cozart, assistant attorney general with the state Department of Justice Transportation Division, told the commission that the temporary sandbags would be installed on the northeast end of the sheet pile bulkhead until the future project now being studied is completed and something more permanent is put in place.

Cozart explained that the bags would be installed in both perpendicular and parallel stacks in a pyramid shape to create more structural stability. The footprint of the perpendicular sandbags would act as a temporary groin system behind the sheet pile wall to allow NCDOT to stabilize the area and protect it until more permanent material is put in place.

Mike Barber, public affairs specialist for Cape Hatteras National Seashore, reiterated that the sandbags are temporary until a long-term structure can be built at the north end of Ocracoke Island.

The National Park Service, which accepted public comments on the project through Monday, anticipates that the environmental assessment for more permanent protection measures it’s preparing with NCDOT and other agencies will be available for review and comment in the fall.

The assessment is to document the effects the proposed structures will have on coastal shoreline processes, human health and safety, wildlife habitat, submerged aquatic vegetation, water resources and the visitor experience. The park service said it will use the document to determine what it will allow NCDOT to do to protect the shoreline, Coastal Review Online previously reported.

The North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review Online, submitted comments to Cape Hatteras National Seashore, explaining that because of the scope of the proposed project, a more thorough environmental study is warranted.

“The proposed solution is short-sighted and does not take into account a long-term, holistic approach to the regional coastal processes. Long-term armoring of the shoreline warrants an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS),” the letter states.

The federation in the letter recommends NCDOT provide a complete analysis of all viable alternatives for the proposed project, including the possibility of relocating the ferry terminal to a more stable location on the barrier island.

Hass added that NCDOT is looking at several different options that include moving the terminal farther south, “but we have just started the study. Other options will be explored as well.”

Hass said that if a terminal groin is used, “models have shown that we will accrue sand between groins, hopefully provide a safer basin for the ferries,” and “allow us to hopefully use the stacking lanes again.”

But, a terminal groin is likely a short-term fix, about 10 or 15 years. “The long-term fix will probably take 10 years or more to study, design, fund and construct,” he said.

“Presently, the department is looking at placing groins perpendicular to the sheet pile wall. This also is considered more of a short-term than a long-term option, especially if the inlet continues to grow in width.”

Commission member Robin Smith expressed her frustration after the variance was granted. Noting that NCDOT didn’t create the conditions, “a lot of decisions and a lot of work done over the course of a very long period of time in an environment that is inherently risky has brought us where we are today,” Smith said during the meeting.

“I would hope that DOT and the park service are thinking very broadly and creatively because continuing on this path of continuing to construct temporary or permanent erosion control structures in this kind of environment is not a sustainable path, in my opinion.”