MANTEO — The North Carolina Ports Authority has cleared a substantial hurdle to expand the ship-turning basin at the Wilmington port.

The third 1,553-ton neo-Panamax crane arrived just last month at the North Carolina Port of Wilmington, or POW, as part of the ports authority’s planned expansion to accommodate new cargo ships, currently the largest calling at East Coast ports.

Supporter Spotlight

With the Panama Canal widened in 2016, the new “ultra-Panamax” vessels, about triple the size of older container ships, are now preferred by shipping companies because of the vast increase in capacity. They are scheduled to call at Wilmington by early 2020.

The state Coastal Resources Commission during its meeting April 17 in Manteo granted the authority a variance to state rules that will permit the turning basin to be expanded again, after a similar enlargement in 2016, to accommodate the new super-sized container ships.

On March 24, the authority submitted a letter to the CRC asking for an expedited variance hearing at the April meeting. A permit application to widen and deepen the turning basin nearly 18 acres was submitted on Oct. 26, 2018. The permit was denied in March, based on the expected damage to fish nurseries and effects on sturgeon that migrate up the river to spawn in late winter and early spring and are protected under the Endangered Species Act.

“If the turning basin is not expanded, those vessels will bypass the POW and call on other east coast ports, thereby causing significant economic impact to the POW and the North Carolina economy,” the State Ports Authority said in its variance request to the CRC. “The POW has the existing infrastructure such as cranes, berths, storage, and transportation to accommodate a 14,000 TEU ship, with the exception of the turning basin.”

TEU stands for 20-foot equivalent unit, a unit of capacity measurement for ships carrying standard 20-foot-long containers.

Supporter Spotlight

According to the State Ports Authority, container ship business garners 48% of the Wilmington port’s roughly $38.2 million in annual revenue and billions more in economic impact across the state.

“The port is trying to meet the demand of the shipping companies,” North Carolina Special Deputy Attorney General Scott Slusser told the CRC. “And if North Carolina doesn’t do it, the other states will.”

Still, Slusser said he understood the division’s “frustration” and vowed to streamline “as much as possible.”

But coastal managers weren’t questioning the economic benefits to the state. Rather, they took issue with the ports authority’s sidestepping communication about the project with division staff and the lack of opportunity provided for public information, input and comment.

“This is not how this process is supposed to work,” said Christine Goebel, general counsel for the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, during a presentation to the Coastal Resources Commission.

DEQ’s Division of Coastal Management, or DCM, enforces the state’s Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, and Dredge and Fill Act and the federal Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972 in North Carolina’s 20 coastal counties. The division serves as staff for the Coastal Resources Commission, which sets policies for the state’s coastal management program and adopts rules for both CAMA and the Dredge and Fill Act.

“If DCM had made a public records request,” Goebel added, “we would have had more information than the ports shared.”

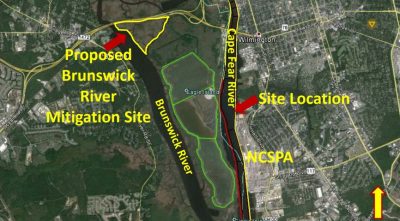

The mitigation proposed by the ports authority, which included a perpetual conservation easement on 30.2 acres of port property east of the Brunswick River, a donation of $800,000 to complete construction and monitoring of a fish passage farther up the Cape Fear River at Lock and Dam No. 1, and tidal marsh enhancement, also didn’t match the size of scale of the dredging, Goebel said.

CRC Vice Chair Larry Baldwin of Harkers Island said he could see the ports authority’s justification for the project, but he also questioned the lack of respect for the process.

“I’m going to echo staff,” Baldwin said. “The lack of public input – I think that’s pretty egregious – and not to let people comment, especially the sister agencies.”

Permits from the Army Corps of Engineers and the North Carolina Division of Water Resources had not been finalized, said Patricia Smith, a spokeswoman for the CRC. The Corps had indicated to the ports authority that it had the capacity for the dredged material at its site on Eagle Island.

In its recommendation to the CRC, the division agreed that in light of Wilmington being the state’s sole port capable of handling the larger vessels, as well as its history of heavy dredging, the economic hardship to the ports related to losing container ship traffic would be greater than the impact to the affected fisheries.

“However, Staff notes that the POW has created some hardships by not openly engaging resource agency staff early in the planning process for the proposed turning basin expansion,” the DCM stated in variance documents.

As an example, the agency said, the ports had commissioned an “Interim Expansion Study” after the successful navigation in 2017 of a super-large ship in the Panama Canal that included analysis of five alternative designs at the Wilmington port. But the study was not shared with the division until April 1 as part of the variance process. Nor were the alternatives analysis disclosed during a pre-application meeting earlier in the fall, or in the permit application. As a result, according to the document, there was no engagement with resource agencies about designs and mitigation plans or their potential environmental effects.

But the ports authority discounted any disconnect with the regulatory agencies.

“North Carolina Ports works closely with the Division of Coastal Management and will continue to work closely with DCM during this project,” State Ports Authority spokeswoman Bethany Welch stated in an email response to Coastal Review Online. “NC Ports’ partnerships with state agencies are critical to the success of this very important project not only for our organization but the entire state of North Carolina.”

The turning basin was enlarged to 1,400 feet wide in 2016, a year after the CRC had granted a variance for larger vessels. But when a 13,092 TEU vessel navigated through the wider Panama Canal in 2017, the shipping industry started favoring use of the super-large vessels.

The $30 million project is estimated to take seven months. Although the ports authority included the delayed starting date of July 1 as part of its mitigation that addresses fisheries impacts, the division noted that the date coincided with when the dredging window would open anyway.

The variance also included additional mitigation measures the division required, including a fish monitoring plan coordinated with state and federal agencies and paid for by the ports. It also required a memorandum of understanding between the ports and the agencies outlining requirements for future projects, including public engagement and coordinated timelines.

“Staff acknowledges the significant economic value of the POW and believes it is within the spirit of the rules to consolidate industrial port activities in the coastal area,” according to the DCM document summing up reasoning for granting the variance.

CRC Chair Renee Cahoon applauded division staff for pulling together a difficult wrap-up of the complicated project.

“A lot of work was done in a short period of time,” she said, “and that’s not the way it’s supposed to be done.”

But in a later interview, Cahoon said the CRC may have been irked, but the panel was well aware that the ports are a major economic driver in North Carolina. The goal is to cooperate and communicate in the best interest of the state, she said, using a process that keeps everyone informed.

“The MOU will solve that problem,” she said, referring to the memorandum of understanding, or agreement on mitigation, required as part of granting the variance. “Sister state agencies will have to work together.”