WILMINGTON – When the long-standing state ban was lifted on terminal groins, a handful of beach towns jumped at the chance to build a case for why a hardened erosion-control structure would be their best line of defense against losing sand.

Nearly eight years after the North Carolina General Assembly repealed the ban in 2011, only one terminal groin has been built.

Supporter Spotlight

The ongoing debate over the structures rages – whether they’re more harmful than helpful in the long term and how much beachfront property they protect.

A lawsuit has stalled one proposed project. After years of studies and hundreds of thousands of dollars expended, elected officials in another town stopped short from applying for a federal permit to build a groin. An environmental group-led campaign launched a yearslong fight against proposed plans for a terminal groin at Rich Inlet.

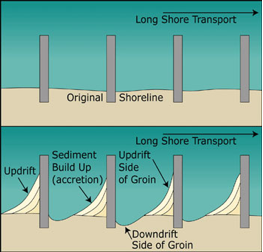

Terminal groins are wall-like structures built perpendicular to the shore at inlets to contain sand in areas of high erosion, like that of beaches at inlets.

When the legislature repealed the decades-old ban of terminal groins on the coast, environmental groups and some of the most prominent coastal scientists in the state spoke out against the rule change.

The North Carolina Coastal Federation went on record opposing construction of terminal groins at any beach in the state shortly after the repeal, which allowed up to four “pilot projects” to be constructed. Months later, the legislature tacked on two more, permitting up to six of the structures to be built on the coast.

Supporter Spotlight

The Rich Inlet Fight

Figure Eight Island, the exclusive, private barrier island in New Hanover County, was the first to kick-start its yearslong process of environmental studies required by federal and state regulatory agencies.

The federation in 2011 launched a “Save Rich Inlet” campaign to educate island property owners about the negative effects a terminal groin would have at the inlet, which is one of the last naturally functioning inlets in the state.

Several property owners at the north end of the island where the terminal groin was proposed to be built made clear they had no plans to grant easements to their properties to the Figure Eight Island Homeowners’ Association. Since the island is unincorporated, the association does not have the authority to condemn private property.

The debate over a terminal groin at Rich Inlet raged for six years. The island got as far as completing a final environmental impact statement, or FEIS, that identified a terminal groin as the preferred erosion-control method at the north end.

In November 2017, the island’s homeowners rejected funding the proposed structure.

There are no plans for a terminal groin on the island.

Turning Tide

As the battle to preserve Rich Inlet raged, three beach towns farther south in Brunswick County were in various stages of seeking federal and state permits for their respective groin projects.

One of those, Holden Beach, became the first to formally revoke its permit application to build a terminal groin since the 2011 repeal. In April 2018, the town’s board of commissioners unanimously voted to permanently revoke the town’s application with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

One pivotal moment leading up to the town board’s decision occurred a couple of years before, when, in April 2016, about 150 property owners gathered for an informational public meeting where coastal experts dissected the town’s EIS. That meeting was, for many in attendance, the first time they heard a different side, one that did not promote a terminal groin.

Some property owners attribute the meeting as the beginning of the shift toward opposing a groin.

The FEIS prepared by coastal engineers hired by the town was released by the Corps in March 2018. The study identified a 1,000-foot-long terminal groin as the preferred erosion-control method at the town’s east end.

The following month, after nearly seven years and more than $600,000 on studies examining various ways to mitigate severe erosion at the Lockwood Folly Inlets, commissioners cast their votes.

In their resolution to revoke the permit application, commissioners explained that the total costs to the town, its property owners and visitors “greatly” outweighed the potential benefits of a terminal groin, which would have cost an estimated $34.4 million for construction, maintenance and routine sand injections needed over the course of 30 years.

The town’s Central Reach project, which cost $15 million and pumped about 1.3 million cubic yards of sand along about a 4-mile stretch of oceanfront in the middle of the island, sufficiently nourished the island’s east end, commissioners concluded.

Court Battle

Holden Beach’s barrier island neighbor to the south, Ocean Isle Beach, remains in a holding pattern with its plans to build a terminal groin.

Ocean Isle Beach’s proposed terminal groin project came to halt in August 2017 when the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a lawsuit on behalf of Audubon North Carolina challenging the town’s FEIS.

The lawsuit against the town and the Corps was filed Aug. 28, 2017, with the Eastern Division of the U.S. District Court of North Carolina. The project to install a terminal groin at the town’s east end started about five years prior to the suit.

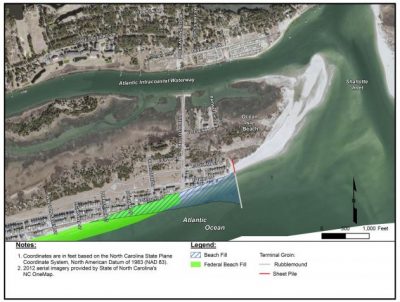

The town was granted a state Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit to build a 750-foot terminal groin, the initial construction cost of which was $5.7 million. The 30-year cost of the project was an estimated $45.8 million.

Construction was expected to begin in fall 2018.

Town Administrator Daisy Ivey said recently that there were no updates in the pending litigation.

So Far, So Good

By all accounts, the first and only terminal groin to be built since the 2011 repeal has fared well through coastal storms, including Hurricane Florence, the most recent storm to directly hit North Carolina.

The Category 1 hurricane made landfall north of Bald Head Island on Sept. 14, 2018, stripping an estimated 215,000 cubic yards of sand from South Beach.

Village Manager Chris McCall said that aerial imagery shows the 1,300-foot-long terminal groin “did well.”

“There’s no appearance of missing boulders,” McCall said. “That shoreline out there and the fillet is still present and stable there. All things being relative, our primary frontal dune system remained intact. The way it came in, (Florence) really hit our friends to the north of us much harder, but our issue in dealing with it really was with the rainfall accumulation over that 72 hours.”

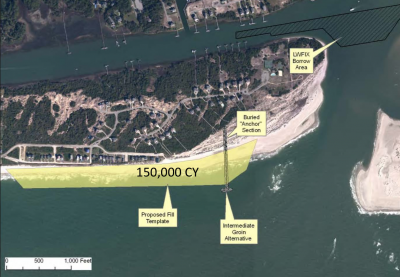

The village is in the midst of mining sand from Jay Bird Shoals and depositing it along South Beach next to the terminal groin completed in early 2016.

The original beach-fill project called for a little more than 1 million cubic yards of sand. After Hurricane Florence, the village added an additional 100,000 cubic yards of sand to the project to make up for sand lost in the storm.

The village’s 2014 federal permit allows for a terminal groin to be built up to 1,900 feet long. Village property owners approved an $18 million bond to secure funding for the project. About $8.5 million has been spent, including the cost of construction. The Bald Head project received state and federal permits to build up to a 1,900-foot-long terminal groin and did not require any easements to private property.

McCall said there had been no talk of proceeding with Phase 2 of the project, which would add another 600 feet to the existing structure.

“I think it’s fair to say we’re relatively fine with just having Phase 1, that it’s working well and it’s providing stability,” he said. “It’s managing (erosion) much better.”

Saving Grace?

North Topsail Beach has been struggling for years to keep sand at its north end on New River Inlet. The Onslow County town has been battling shoreline erosion south of the inlet since 1984, the year the inlet’s bar channel shifted toward an alignment with Onslow Beach.

Erosion has claimed several homes since then.

The town’s channel-realignment project completed in early 2013 failed to curb erosion at the north end.

A huge sandbag revetment some 45-feet wide and 20-feet tall is providing temporary protection for oceanfront homes.

The wall of sandbags connects to a revetment Topsail Reef Condominiums had installed after receiving a state permit in 2012 to build one larger than the maximum the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission, or CRC, typically allows.

The bags are permitted through 2022.

As the countdown to that permit expiration ticks away, some in the town believe their saving grace will be a terminal groin.

Applied Technology and Management Inc., or ATM, the firm hired by the town to pursue a hardened structure project, recommends a two-phase terminal groin project, similar to that of Bald Head Island.

ATM suggests the town build a 1,500-foot structure with the permits to add an additional 500-foot anchor later if needed.

But plans for the proposed project have been placed on hold.

The devastation from Hurricane Florence forced the town to shift its focus to restoring its dune system, which suffered an estimated $22 million loss.

“There is a draft EIS that is still in the works,” North Topsail Beach Town Manager Bryan Chadwick said. “We’re pursuing this, but it is going to come down to the fiscal responsibility of taking care of priorities. Although this is a priority, we are still in a recovery mode.”

The roofs of several homes remained draped in tarps. Parks and public parking lots must be restored.

Town officials did not have an estimate of when the draft EIS will be ready.

Onslow County commissioners agreed in July 2016 to a $250,000 match to the town’s contribution toward paying for the EIS.

Commissioners made clear their primary interest is in stabilizing the inlet for navigational purposes, raising the question of whether they would support a terminal groin, a structure built to stabilize shorelines.

“We have not talked with them about any type of financial support for construction of a terminal groin,” said North Topsail Commissioner Joann McDermon. “I think it would be premature at this point to do that.”