WILMINGTON – The proposed consent order between Chemours and the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality would be the quickest way to stop pollution emanating from the company’s Fayetteville Works plant, officials with environmental groups that joined the order say.

Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette and Southern Environmental Law Center Senior Attorney Geoff Gisler defended why they joined a consent order that would require the company to pay a $12 million penalty, reduce air emissions of GenX immediately and clean up and decrease per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance, or PFAS, contamination in the Cape Fear River.

“What this order does is attack all of those sources of pollution,” Gisler said as he pointed to a diagram projected onto a large screen showing how compounds produced at the plant get into the river. “What this order does do is it turns off the spigot.”

Gisler and Burdette fielded questions during a public meeting Wednesday night on the campus of the University of North Carolina Wilmington, explaining their reasons for joining the consent order that, if approved by a Bladen County judge, would grant the nonprofit Cape Fear River Watch equal enforcement power as DEQ.

The proposed consent order does not have the support of the local utility authority or some elected officials, who argue the agreement fails to address Cape Fear River sediment and drinking water contamination issues.

Supporter Spotlight

New Hanover County Commissioner Woody White recently asked fellow commissioners to join the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority, or CFPUA, in opposing the agreement by adopting a resolution stating as such.

White addressed several concerns in an email to county officials, including the fact that neither the utility, county nor city were involved in the settlement negotiations.

He questioned whether the settlement could adversely impact the utility’s lawsuit against Chemours, whether River Watch’s compliance oversight would be a conflict of interest in relation to fundraising, and argues the agreement fails to hold Chemours accountable for knowingly discharging PFAS into the Cape Fear River for more than three decades.

Burdette and Gisler were asked during Wednesday’s Q&A session about the concerns raised by White and the CFPUA.

“It is, in fact, our job to protect water quality,” Burdette said. “(The order) does not give us oversight above and beyond what the state has. (White) may have thought it appeared to do that, but it does not do that.”

Gisler said the agreement does not foreclose any future remediation Chemours may have to address nor will it impact future lawsuits brought against DuPont.

“Our focus in these cases was stopping the pollution,” he said. “They were, by design, intended to focus on what’s happening now.”

Cutting off the pollution source and keeping it on site is an essential part of solving the problem, but it is not the entire resolution to the problem, he said.

River sediment, for example, is not addressed in the agreement.

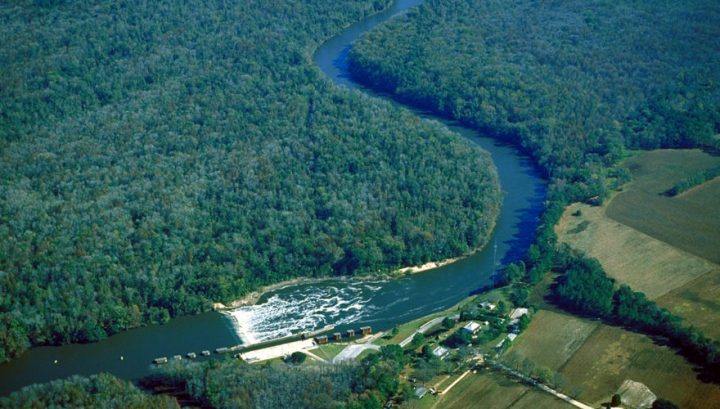

“Contaminate in sediment is a difficult thing,” Burdette said. “The Cape Fear Public Utility Authority has indicated that they have concerns about the sediment and they have a lawsuit to address that. We could spend two decades trying to figure out the exact specifics of sediment or we could stop the pollution that’s leaving that site and affecting our drinking water now.”

The 36-page consent order lays out how much pollution must be reduced within specific timeframes.

Chemours would be required by Dec. 31 to reduce facility-wide air emissions of GenX by at least 92 percent from 2017 total reported emissions.

The company by the end of 2019 would have to reduce GenX compounds by at least 99 percent from 2017 emissions.This requirement would be included in future air permits granted by the state.

The agreement also mandates that Chemours provide the state with tests for all PFAS the company knows about so that DEQ can test for those compounds.

Discovery of any new PFAS would have to be reported to the state as well as any new process that may cause new compounds to be discharged from the plant.

“There’s a number of steps being taken to manage the groundwater contamination,” Burdette said.

Chemours would continue to collect its polluted wastewater and truck it offsite and cooling ponds would be lined.

The company would have to provide filters to residents who rely on groundwater near the facility.

Sampling plans are still being hashed out, but the order sets up a process for sample and remediation plans, Gisler said.

The agreement does not address possible adverse health effects to those exposed to the chemicals in their drinking water.

Gisler and Burdette anticipate that class action lawsuits will likely be filed against the company pertaining to health-related issues.

The consent order, Burdette said, is the very first step.

“It stops contamination from leaving the site and entering the river, which is the water we drink,” he said. “Our real goal here, the Cape Fear River Watch mission, is protecting and improving the Cape Fear River. I think what is important is we’re pushing for a quick stop to the source. I think that it will be a real blow to this community if we don’t do what this consent order will do. I certainly don’t think it’s the last step.”

Burdette encouraged the audience to submit comments on the proposed order to DEQ.