HOLDEN BEACH – A terminal groin at the east end of Holden Beach was a given.

The town board had unanimously supported legislative efforts to allow the hardened structures at North Carolina inlets as a way to control beach erosion.

Supporter Spotlight

In the fall of 2011, the year the General Assembly repealed the decades-old ban on terminal groins, initially allowing up to four be built, town commissioners at the time passed a one-page resolution authorizing the town manager to apply for a state permit to build one at Lockwood Folly Inlet.

Word around the barrier island town was that the structure would cost a mere $1.5 million, that it would be funded by higher government and provide hurricane protection.

“Basically, all our dreams will come true,” recalled Tom Myers, president of the Holden Beach Property Owners Association.

When the organization decided to include the terminal groin as a topic in a 2015 survey of property owners, the feedback was clear – a majority of people could not make up their mind as to whether they supported or objected to a terminal groin. They wanted more information.

So those at the helm of the property owners’ association obliged, setting off on what became a collaborative information-gathering mission that would eventually turn the tide from “this is a must” to “this is not what’s best” for the town.

Supporter Spotlight

A Deeper Look

“We did not set out to kill the groin,” Myers said. “That wasn’t our objective. We set out to get to the bottom of the information.”

Ronda Dixon, who owns a home in Dunescape, a gated community at the far eastern end of Holden Beach, was one of the property owners who wanted to learn as much as she could about the proposed structure.

“It took a lot of time and effort of everyone’s part,” Dixon said. “It was a major, major project.”

The draft environmental impact statement, or EIS, on the proposed project was released for public review by the Army Corps of Engineers in August 2015.

The document was compiled by a firm hired by the town to examine the effects on inlet- and shoreline-stabilization alternatives.

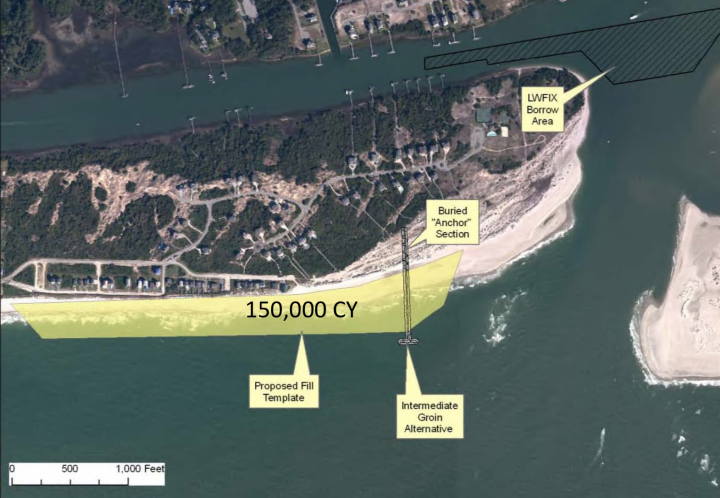

It gave property owners their first real look into what was being proposed: a 1,000-foot-long terminal groin with an estimated $34.4 million cost associated with construction, maintenance and routine sand injections needed to supplement the structure over 30 years.

That information was brought to light during an April 2016 public meeting in the town, where about 150 property owners gathered in a local chapel and listened as coastal experts dissected the EIS.

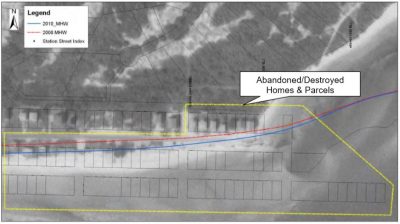

A terminal groin would provide erosion protection to a much smaller number of homes than reported in the EIS, protect less than $1.2 million in tax revenue over 30 years and push chronic erosion at the east end of Holden Beach to spots further down the barrier island, experts argued.

“Honestly, it was the first time a majority of people heard from the other side,” Myers said. “We got criticized for it being one-sided. We invited everybody we could think of on the other side.”

Proponents of the proposed terminal groin, including representatives with Dial Cordy and Associates, the environmental consulting firm that compiled the EIS, did not attend.

“I think that meeting was the very beginning of when the tide started to change,” Myers said. “It started to snowball from there.”

“It was interesting because everybody who started to look at the facts started to come around.”

Tom Myers, president, Holden Beach Property Owners Association

The POA started to record a fact sheet, which included information such as the projected costs and the long-term maintenance and re-nourishment cycles associated with the proposed terminal groin.

“We tied every fact to either the draft EIS or the beach inlet report,” Myers said. “It was interesting because everybody who started to look at the facts started to come around.”

The property owners association’s 2017 survey revealed that about 80 percent of those polled either opposed a terminal groin or were still on the fence. Twenty percent said they supported the proposed project.

The survey results came in before the association hosted its meet-the-candidates forum held before the November 2017 municipal election. The seven candidates running for town commissioner were asked to state whether they supported or opposed a terminal groin.

“The five that came out on record that they were against it were the five who were elected,” Myers said. “I think that’s pretty telling.”

A Final Vote

Through the years, the property owners association has taken its concerns to commissioners related to issues including noise, parking and cabanas left overnight on the beach – typical topics in small beach towns along the North Carolina coast.

“(The terminal groin) was totally different because we were taking on a train that left the station and had taken on a whole lot of momentum,” Myers said. “What we were taking on was the system was against us. To take on something like that around was a lot more work. It took a lot more research on our end and lot more digging into the facts. It was going to have an enormous impact on our property taxes. It was probably the biggest financial impact to our members. We wanted to bring the town to the right decision and we wanted to bring the town to the best decision.”

In April, about a month after the final EIS was released, the town board unanimously voted to withdraw the town’s permit application with the Army Corps of Engineers.

Commissioners concluded that, “the total costs to the Town, its citizens and visitors of the proposed Lockwood Folly Inlet Terminal Groin greatly outweigh the potential benefits thereto, both financially and otherwise,” according to a resolution they unanimously adopted following their vote to revoke the application.

Holden Beach is the only North Carolina beach town to formally revoke its permit application to construct a terminal groin since the ban on the structures was repealed.

Commissioner Peter Freer said the town is not abandoning or ignoring erosion at the east end. The board is making sure there’s budgeted funds to get sand dredged from the inlet by the corps of engineers to place on the east end.

More than a year ago, the town completed the first phase of its $15 million Central Reach project, which pumped about 1.3 million cubic yards of sand along about a 4-mile stretch of oceanfront in the middle of the island.

Commissioners also established in April an inlet and beach protection board to serve in an advisory capacity to the town.

The town, the Holden Beach Property Owners Association and the Dunescape Property Owners Association recently received a North Carolina Coastal Federation Pelican Award for exceptional coastal stewardship.

“When I first got involved it was a foregone conclusion that a terminal groin was going to be built,” Freer said. “It wasn’t solve the problem of erosion on the east end, it was build a terminal groin. It took a long time to change that foregone conclusion to what I felt was an easy decision. From my point of view, it didn’t make sense technically, environmentally or financially. It was actually very satisfying that the process worked.”