SUNSET BEACH – Acres of pristine, building-free oceanfront land stretching between the last house on the west end of Main Street in Sunset Beach and the Bird Island Coastal Reserve could be state-owned in the months to come.

The state budget includes $2.5 million to buy the land, an offer that, if accepted, will close the book on a contentious fight with a story that has as many twists and turns as the inlet that once meandered through the property.

Supporter Spotlight

If the deal goes through it will be a fairy tale ending for those who’ve fought to keep the land development-free and pad the pockets of the developers who’ve envisioned building an exclusive seaside neighborhood on the property.

It is unclear when the state may buy the land. A spokesperson for the North Carolina Department of Administration, which includes the state property office, did not respond to a request for comment.

Developer Sammy Varnam responded in a text, “Per the settlement agreement with the town of Sunset Beach, we offered to sell the 25 acres of ocean front property to the state of North Carolina for the Bird Island expansion.”

News that the state budget includes money to buy the land elated Sunset Beach property owners who’ve been at the helm of a yearslong battle to prevent building on the land.

“My heart is just jumping around,” Sunset Beach resident Sue Weddle said. “I think for all of us who were so determined there was never any question it was going to end up being in public domain. It’s past wonderful. This means from the start of Mad Inlet to Little River Inlet there is a piece of the North Carolina-South Carolina coast that remains as it was from time immemorial. That is really special and unique.”

Supporter Spotlight

Weddle and fellow Sunset Beach resident Frank Nesmith, the man known as the Bird Island “mayor,” worked tirelessly to preserve the 1,400-acre reserve adjacent to the town.

“I was tickled to death over that,” Nesmith said of the state’s 2002 purchase of the reserve. “I couldn’t believe it happened when it happened, but it happened. Now, I can’t believe that I’m hearing the rest of the land will be preserved. It’s just wonderful.”

The 91-year-old is no longer able to walk the length of beach stretching in front of the reserve. He handed over his duties as the keeper of the “Kindred Spirit” mailbox, a nationally recognized fixture at Bird Island, years ago.

But, he said, he gets joy out of knowing that the land will be there for future generations to enjoy.

“I’m fortunate to see this this happen, if it happens,” he said.

Weddle and Nesmith have been part of a group of Sunset Beach property owners, environmentalists and conservationists who’ve raised their opposition against development of the land.

Sunset Beach Town Councilwoman Jan Harris joined the ranks of the group after moving to the resort town as a full-time resident more than 20 years ago.

“We won one. We don’t win many, but this one, we won,” Harris said. “To me it’s a big one because, look at that view where the ocean meets the land the way God made it and it’s there for our grandchildren and great-grandchildren. It’s really kind of overwhelming to me when I think about what is down there that has been saved. Every bit of the hard work was worth it.”

Mad Inlet No More

Their fight started in 2010, the year the science panel that advises the state Coastal Resources Commission, or CRC, recommended removing Mad Inlet from the inlet hazard area designation.

By then, the shallow inlet that once meandered between the Brunswick County town and the protected coastal reserve had been dried up for more than a decade.

Inlet hazard areas, or IHAs, are defined as shorelines especially vulnerable to erosion and flooding where inlets can shift suddenly and dramatically.

Building is more heavily regulated within these coastal areas.

The town, backed by environmental groups, went on record opposing the science panel’s recommendation.

But in February 2014, the CRC lifted the designation, determining that the inlet would not likely reopen.

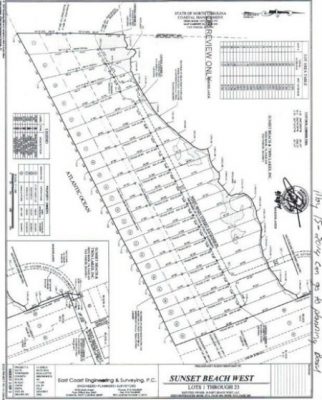

The following May, the town received preliminary subdivision plans depicting a 23-lot subdivision with a private, 30-foot-wide wooden bridge crossing over marsh and wetlands to the property.

Sunset Beach West LLC, formed by descendants of Mannon Gore, along with Varnam, was gearing up to develop a posh, gated community on the land.

Gore’s legacy goes back to the late 1950s, when the Brunswick County native began laying the foundation for the seaside community. His son, Ed Gore Sr., followed in his father’s footsteps, building homes that would fulfill the dreams of those yearning to own a slice of island life.

Development Challenges

The proposed neighborhood would offer exclusivity and spectacular water views from houses built on large, oceanfront lots.

Sunset Beach West developers initiated a monthslong process to obtain several local and state permits required to build on the land.

Though the property had been removed from the IHA, it is in a federal zone defined by the Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA (pronounced “cobra”).

Utilities in CBRA zones cannot be built or maintained by federal tax money. Property owners in these zones are not eligible for federal flood insurance or any other federal assistance.

Varnam’s plan to run private lines to connect to Brunswick County’s water and sewer service seemed to be unfolding smoothly when commissioners voted in September 2014 to grant his request.

A few months later, the board rescinded that vote after receiving a letter from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service warning of possible implications the county could face if service was provided to a CBRA zone.

A wildlife service official explained that even establishing connections outside of the CBRA zone and allowing public utilities to travel through private pipes could cause the county to be cut off from receiving future federal funds.

It was a risk commissioners were not willing to take.

Varnam insisted he would move forward with the development, installing private water, sewer and electric utilities if necessary.

A Question of Ownership

The developer’s plans would face another obstacle in early 2016, when the town began questioning just who owned the land.

After digging through records and past town council meetings, the town’s attorney discovered that the town may be the rightful owners the property.

Varnam emphatically disputed the town’s claim, saying he has the deed to the property.

In June 2016, he received all the state and federal permits needed to move ahead with the project. His next step was to obtain local permits.

But one day after the North Carolina Division of Coastal Management granted Varnam a Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit, the Sunset Beach council voted unanimously to take its claim that the town, not the developers, owned a majority of the land, to court.

The dispute goes back to 1987, when Ed Gore deeded a portion of the land to the town on condition the town use it to build a public parking lot within three years. The parking lot was never built.

In 2004, the town council passed a resolution declaring that a parking lot would be too expensive because the town would have to either buy the last developed oceanfront lot at the west end of Main Street or build a bridge to access the land on which a parking lot could be paved. The town board decided to turn the deed back over to the Gore family.

The town, however, never prepared the deed and the family did not request it. Meanwhile, the Gores continued to pay taxes on the land.

In 2016, before filing its lawsuit in Brunswick County Superior Court, the town council rescinded the board’s 2004 vote.

A Resolution

More than a year after the lawsuit was filed, a proposal was brought to the table that placated both sides.

On Nov. 21, 2017, the town council unanimously accepted a memorandum of agreement granting the developers the right to negotiate selling the land to the state.

A Brunswick County Civil Superior Court judge, at the town’s request, placed the lawsuit on inactive status.

The terms of the memorandum allow for only the developers to discuss selling the property with state officials and, if the state buys the land, it has to agree to keep it from development, walking trails, paths or structures of any kind.

The developers, not the town, would receive the profit from a sale.

If the developers decline the state’s offer, the lawsuit would be re-initiated, re-opening the possibility of a long, drawn-out legal battle.

“They didn’t own it to start with but they’re getting the money for it and I’m OK with that because we get what we want,” Harris said. “There will be no unnatural building of any kind. There will be no boardwalks. There will be no walkways. There will be no benches. It will be kept just as it is right now and I’m very happy with that. We have saved that forever.”