HOLDEN BEACH – Holden Beach commissioners are withdrawing the town’s permit application to build a terminal groin at the east end of the barrier island.

“… the total costs to the Town, its citizens and visitors of the proposed Lockwood Folly Inlet Terminal Groin greatly outweigh the potential benefits thereto, both financially and otherwise.”

Holden Beach Board of Commissioners

During their regular meeting Tuesday night, board members unanimously voted to permanently revoke the town’s application with the Army Corps of Engineers.

Supporter Spotlight

Commissioners have concluded that, “the total costs to the Town, its citizens and visitors of the proposed Lockwood Folly Inlet Terminal Groin greatly outweigh the potential benefits thereto, both financially and otherwise,” according to a resolution they unanimously adopted following their vote to revoke the application.

Commissioners directed attorney Clark Wright, a special environmental lawyer hired last December by the board, to notify the Corps of Engineers of the board’s decision to “withdraw fully and cease any and all further processing of, or action on” the permit applications and associated National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, documentation.

Federation Applauds Action

The North Carolina Coastal Federation, publisher of Coastal Review Online, has been against the terminal groin since it was first proposed.

“It is great news that the town will not be pursuing this destructive process,” said Todd Miller, executive director of the federation. “Town officials have been receptive in listening to the negative impacts of a terminal groin, which are extremely expensive and not guaranteed to work.”

The federation noted in a press release that its opposition to terminal groins and similar hardened structures is because of the threats they pose to public beach access and natural habitat for endangered or threatened species, including sea turtles and shorebirds.

Supporter Spotlight

The town has spent nearly seven years and more than $600,000 on studies examining various ways to mitigate severe erosion at the Lockwood Folly Inlet.

The final Environmental Impact Statement, or FEIS, a study prepared by coastal engineers hired by the town and released by the Corps last month, identified a 1,000-foot-long terminal groin as the preferred erosion-control method.

Terminal groins are wall-like structures built perpendicular to the shore at inlets to contain sand in areas of high erosion, like that of beaches at inlets.

What’s Best for the Town

Board members did not discuss why they chose to revoke the permit application before casting their votes, but the two-and-a-half-page resolution states that the analyses in the draft EIS and FEIS use out-of-date data, “without regard to more recent coastline and inlet changes.”

At the close of the meeting, Commissioner John Fletcher said everyone on the board thoroughly researched the environmental studies before making the decision to revoke the permit application.

“I think everybody made the decision on what they felt was best for the town individually,” Fletcher said. “My view is to keep the nine miles of beach beautiful.”

Engineers with Applied Technology and Management Inc., or ATM, identified a 700-foot-long terminal groin with a 300-foot-long shore anchorage system as the preferred alternative to shoreline erosion control at the island’s east end.

Fran Way, a senior coastal engineer with ATM, said earlier this month that the town would save $12 million over 30 years if it builds a terminal groin. During that April 6 meeting, Way encouraged commissioners to move ahead with obtaining the permits.

O’Neal Varnam, a Brunswick County resident who has been coming to the island for decades, asked commissioners Tuesday night to proceed with the proposed groin project.

“It would catch the sand,” he said. “This is something that’s really serious. We need to talk about it. You really need to think about this thing.”

Better Off Re-Nourishing

Opponents of the terminal groin have argued that the estimated $34.4 million cost associated with construction, maintenance and routine sand injections needed to supplement the structure over 30 years is too high a price tag to protect what would equate to protection of a handful of homes at the east end.

Several people who spoke during the April 6 meeting about the FEIS said the town would be better off re-nourishing the beach.

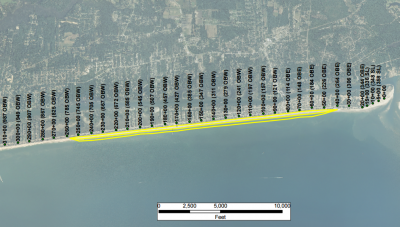

The town has been routinely pumping sand onto the eastern end of the 8.1-mile-long barrier island for 50 years. Sandbags have also been placed along the shore throughout the years as a temporary means to protect homes and properties.

About a year ago, the town completed the first phase of its $15 million Central Reach project, which pumped about 1.3 million cubic yards of sand along about a 4-mile stretch of oceanfront in the middle of the island.

The resolution commissioners adopted Tuesday acknowledged the Central Reach project and “significant beach nourishment on the East End, including beach nourishment utilizing low cost sand available as a by-product of the continued dredging of the Lockwood Folly Inlet at costs orders of magnitude lower than costs utilized by the USACE in the DEIS and FEIS.”

Ronda Dixon lives on an oceanfront lot at the east end. If the town had proceeded with building a terminal groin, the structure would have been built on a portion of her property.

“I think that (the permit application revocation) was the best possible decision for Holden Beach and for all the taxpayers,” Dixon said. “It was not done lightly. It was a tremendous amount of work and research that went into the formulation of that decision and I’m very happy with the result.”

Dixon said she suspects discussions about building a terminal groin at the east end will “come back again.”

“But at that time my hope is that they will start from scratch and look at updated data,” she said.

First to Back Out

Holden Beach is the first North Carolina beach town to formally revoke its permit application to construct a terminal groin since the General Assembly in 2011 repealed a decades’ old law banning coastal hardened erosion control structures.

The law allows for the construction of up to six terminal groins along the coast.

Bald Head Island is the only beach town in the state to build a groin since the 2011 repeal.

Figure Eight Island, a private barrier island in New Hanover County, got as far as seeing through the completion of an FEIS that identified a terminal groin as the preferred alternative at Rich Inlet. Property owners voted down the proposed project.

Ocean Isle Beach’s plans to build a terminal groin have been on hold since August when a lawsuit challenging that town’s FEIS was filed by the Southern Environmental Law Center on behalf of Audubon North Carolina.

North Topsail Beach in Onslow County is in the early stages of studying erosion-control alternatives at New River Inlet. Coastal engineer consultants hired by that town said that the preliminary preferred alternative to mitigate erosion at the northern end of town is a 2,000-foot-long terminal groin.