This Google Timelapse spanning 1984-2016 shows the naturally occurring western movement and eventual filling in of the small inlet that once separated Bird Island from the west end of Sunset Beach.

SUNSET BEACH – The Sunset Beach Town Council has agreed to ask a judge to place its lawsuit over a land ownership dispute on “inactive status” while it waits for the state to decide whether to buy the property.

Supporter Spotlight

The question now is whether the state will purchase the 35-acre tract at the west end of town and deem it conservation land, a fate both the town and the developers named in the lawsuit agreed upon last month through mediation.

Town council members unanimously voted Nov. 21 to accept a memorandum of agreement, which grants the developers the right to negotiate selling the land to the state.

A Brunswick County Civil Superior Court judge has to rule on the agreement before it may be carried out. The town and defendants listed in the lawsuit are scheduled to appear in court Dec. 8 to ask the judge to place the lawsuit on inactive status, “to give the State adequate time to acquire the funding to purchase all of the property,” according to the agreement.

Among the stipulations listed in the memorandum, only the developers may discuss selling the property with state officials unless one of the defendants specifically requests the town to communicate with the state.

The developers have initiated talks with the state, according to the memorandum, which reads, “Defendants informed the Town of its recent discussions with members of the North Carolina General Assembly about the possibility of the State of North Carolina (“State”) purchasing all of the Property for permanent and perpetual conservation …”

Supporter Spotlight

If the state buys the land, it has to agree to keep it free from development, walking trails, paths or structures of any kind.

The developers, not the town, would receive any profit from a sale.

“The impetus is now on the developers,” Sunset Beach Mayor Robert Forrester said. He added that the town agrees with “the intended result.”

The agreement comes after the town in the summer of 2016 filed a lawsuit against Sunset Beach West LLC, Sunset Beach & Twin Lakes Inc., and the co-executors of the estate of the late Edward Mannon “Ed” Gore Sr. Co-executors include Gore’s widow, Dinah Gore, who is listed as president of Sunset Beach & Twin Lakes Inc., and son, Gregory Gore, co-owner of Sunset Beach West LLC.

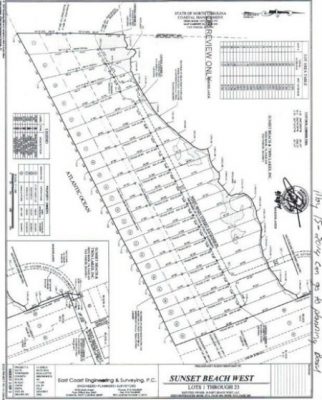

The lawsuit stopped short initial construction of an upscale development that would include 21 homes.

Developer Sammy Varnam, co-owner of Sunset Beach West LLC, had already obtained federal and state permits, including a Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit to build a bridge and docking facility on the property.

Varnam submitted a general warranty deed to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality in April 2014 when he applied for the CAMA major permit. A DEQ official stated then that it was not the department’s responsibility to settle a dispute over the validity of a deed.

Town officials and attorneys with the Southern Environmental Law Center initially raised questions in the fall of 2015 about whether the limited liability company owned all of the land, including the right-of-way to the property.

Varnam maintains that his company owns the land that stretches between where the pavement ends at West Main Street to the Bird Island Preserve.

He declined to comment for this article.

The debate goes back to 1987, when Ed Gore Sr., a well-known Sunset Beach developer and businessman, deeded a portion of the land to the town on the condition the town use it to build a public parking lot within three years. The parking lot was never built.

The town council in 2004 passed a resolution declaring that a parking lot would be too expensive because the town would have to either buy the last developed, oceanfront lot at the west end of West Main Street or build a bridge to access the land on which a parking lot could be paved. The town board decided then to turn the deed back over to the Gore family.

The town, however, never prepared the deed and the family did not request it. Meanwhile, the Gores continued to pay taxes on the land. Ed Gore died in July 2014.

In early 2106, the town council rescinded the 2004 vote.

“The ownership was the real issue,” Forrester said. “There’s no recognition as to who owns it. There’s been no definitive determination.”

Sunset Beach Town Administrator Susan Parker said she cannot discuss how the town and developers came to the agreement.

“The next move is for the other party to initiate discussions with the state or continue discussions with the state,” she said. “We didn’t put a timeline on it because we do not know how fast the state will or will not move.”

Longtime Sunset Beach resident Sue Weddle said that while she would like to see the state buy and preserve the property, she believes the town should receive any sales revenue.

“Ed Gore gifted that land to the town,” she said. “He had three years to take it back if he wanted to. He never did. That land is the property of the town. I am so sorry that the town and the lawyer agreed to something that they had no right to agree to. The money goes to we the citizens.”

Weddle is among a group of property owners in the town who’ve been opposed to the proposed Sunset Beach West development from the start.

The neighborhood would be built on land that was once Mad Inlet, a shallow channel that opened and closed over the centuries and dried up in the mid-1990s.

The inlet separated the west end of Sunset Beach from what is now the Bird Island Reserve.

In February 2014 the North Carolina Coastal Resources Commission removed it from the inlet hazard area designation.

The land remains in a federally designated Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA (pronounced “cobra”) zone. Building is allowed in CBRA zones, but, in an effort to discourage development in these areas, the government restricts federal subsidies, including flood insurance and Federal Emergency Management Agency aid.

If the judge denies the request to place the lawsuit on inactive status, the town and the defendants have agreed to file voluntary dismissals within 15 days of that ruling.

If the state declines to buy the land, the lawsuit could resume.