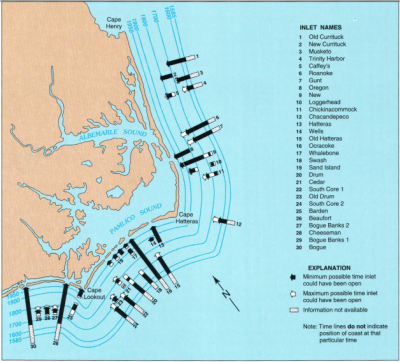

For a brief period in North Carolina’s early history, the only passage from the Atlantic Ocean to the sounds protected by North Carolina’s Outer Banks was through Ocracoke Inlet, an entry that supported small but thriving villages on Ocracoke and, especially, Portsmouth Island. But in September 1846, that changed as a powerful, slow-moving tropical system opened Oregon and Hatteras inlets, changing transportation patterns along the coast and wreaking havoc at sea.

As the storm passed, eyewitnesses described the formation of Oregon Inlet.

Supporter Spotlight

On Sept. 8, 1846, Calvin Midgett, an Outer Banks farmer, fisherman and part-time employee of the U.S. Coast Survey, the nation’s official nautical chart maker and predecessor of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, watched helplessly as the fury of the hurricane created Oregon Inlet at his home’s doorstep.

Midgett had been working at the time with assistant superintendent of the Coast Survey Charles Otis “C.O.” Boutelle to create a detailed map of the Outer Banks.

Gale-force winds had blown from the northeast for two days and, according to Boutelle, “… the sound waters were all piled up to the southwest.”

“… A sudden squall came from the southwest, and the waters came upon the beach with such fury that Mr. Midgett, within three quarters of a mile of his house when the storm began, was unable to reach it until four in the afternoon. He sat upon his horse, on a small sand knoll, for five hours, and witnessed the destruction of his property, and as he then supposed of his family also, without the power to move a foot to their rescue, and, for two hours, expecting every moment to be swept to sea himself.”

Midgett’s house was damaged; his family members, though, were alive and well. When the sun had finally broken through, Boutelle and Midgett inspected the shoreline, looking for changes.

Supporter Spotlight

The storm was part of a slow-moving system. A day earlier on Monday, Sept. 7, Portsmouth Island had been battered. Sarah Clark was there, visiting friends, and the letter she wrote to her husband, Samuel, gives a chilling firsthand account of the storm’s severity.

“You could hear the tide slopping against the floor; you cannot imagine how bad it did sound. The inhabitants say that it was the hardest wind that they have had in twenty years. The highest tide was at ebb. They say that it would have been one and a half foot higher if it had been flood … I can count ten or twelve vessels ashore around here and I have not heard how many on Ocracoke.”

At sea, the storm tracked north.

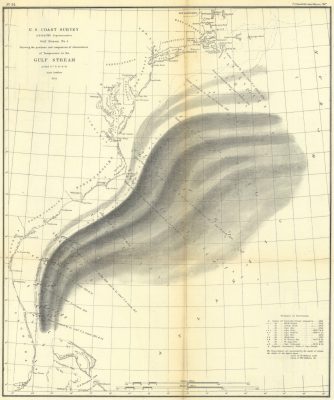

The U.S. survey brig Washington was bearing north under Lt. George M. Bache’s command. The great-grandson of Benjamin Franklin and the brother of the Superintendent of the U.S. Coast Survey, Alexander D. Bache, George Bache had been taking a series of readings to more precisely mark the course and location of the Gulf Stream.

The 1846 expedition was one of a series of missions the Coast Survey had undertaken with the goal of creating a detailed map of the eastern and southern shoreline and adjacent seas.

As Lt. Bache took readings off the coast of North Carolina, he discovered a remarkable phenomenon: a seemingly permanent wall of cold water separating the Gulf Stream from nearshore currents and waters. His letter to his brother in August of that year is part sibling affection, part wide-eyed wonder and part pure scientist.

“I would like to be with you when you look at and admire this section, as admire it you must, and speculate on it together,” he wrote. “Here on the left we have the main current of the stream turned to the eastward, by Cape Hatteras, and butting up against a bank of cold water, which it overflows, and on the right mingling with a vast reservoir of warm water, which is probably brought there by the eddies from the stream itself. How beautifully the Basis defined to the left or westward, and how well the observations of the 2d of August come in to verify the others!”

It had been a difficult year for storms, Bache wrote his brother. “We were 21 days off soundings in the Gulf stream and its offset, and in that time had 15 bad nights – squalls of wind … rain sometimes in torrents, with lightning generally.”

The early September storm would prove to be the worst.

The ship’s log for the evening of Sept. 7 notes “… a fresh breeze from the northward and eastward, with a heavy swell from the southward and eastward …” At midnight the Smith Island, Virginia, light was sighted, but concerned about reefs along the Virginia Banks, Bache “… wore ship to the southward and eastward.”

The weather continued to deteriorate. By the following afternoon, “From 4 to 8, heavy gales from the northward and eastward; thick haze and rain, with a heavy sea on.”

That was followed by the 10 p.m. entry, “At 10, blowing a hurricane, the water above the lee rails most of the time; hove overboard both of the lee guns, and cut away the mainmast, which brought the fore topmast, the fore yard, and the head of the foremast with it leaving them hanging up and down the mast.”

And then, at 10 minutes after 11, as Lt. John Hall wrote, “… while in the act of letting go the starboard anchor, shipped a heavy sea amidships and on the quarter, sweeping the deck fore and aft, and carrying with it the poop cabin, and nearly all the officers and men. She partly righted; all succeeded in getting on board again, with the exception of George M. Bache, lieutenant commanding, James Dorsey, Benjamin Dolloff, and John Fishbourne, quarter masters, Henry Shroeder, sailmaker’s mate, Francis Butler, Lewis Maynard, Thomas Stamford, and William Wright, seamen, and Peter Hanson and Edward Grennin, ordinary seamen.”

Badly damaged and absent its commander, the ship survived the night and the surviving crew began rigging temporary sails to limp home. Four days later, off Cape Hatteras, the U.S.-flagged brig J. Peterson sighted the ship and stayed with it until the USS Constitution, returning from a mission to Rio de Janeiro, overtook the crippled vessel and towed it to Philadelphia. The ship was repaired, eventually returning to duty.

The September storm changed the shoreline of the Outer Banks dramatically. Oregon and Hatteras Inlets became new shipping channels to the interior of the state. Although the side-wheeler Oregon passed through the new northern inlet soon after it opened, providing its namesake, what became known as Hatteras Inlet was the wider and deeper of the fresh passages.

Sarah Clark and her friends on Portsmouth Island could not know it at the time, but the opening of Hatteras Inlet would eventually diminish Portsmouth Village’s importance, as shipping turned increasingly to the more northern inlet.

Boutelle, in writing about the new inlets, confirmed Bache’s observation that 1846 had been a particularly stormy year, noting that it was the series of storms that created the circumstances that ultimately formed the new inlets.

“The force of the water coming in so suddenly, and having a head of two to three feet, broke through the small portion of sea beach which had formed since the March gale, and created the inlets. They were insignificant at first – not more than 20 feet wide – and the northern one much the deepest and westerly winds which prevailed in September, the current from the sound gradually widened them …”

Oregon Inlet, though, soon became the lesser of the two new passages.

“The northern one has since been gradually filling, and is now a mere hole at low water,” Boutelle wrote. “… At the bar our boat would not float over with the men in her. During the time I remained at Bodie’s island, it filled considerably.”