SUPPLY – How does it affect humans? How does it react in the air? What about the fish that live in the river where it has been discharged for decades?

Even as Chemours faces revocation of its wastewater discharge permit at its Fayetteville Works facility, questions continue to mount about the chemical known as GenX and other chemical compounds the former DuPont plant has been releasing into the Cape Fear River and the air.

Supporter Spotlight

Larry Cahoon, a professor of biology and marine biology at the University of North Carolina Wilmington, posed many of those same questions when he spoke to a group of Brunswick County residents Monday evening in the Brunswick Electric Membership Corp. meeting room. Cahoon said he was not speaking on behalf of the university.

Before he delved into the subject of GenX at the meeting hosted by the Brunswick Environmental Action Team, or BEAT, a Brunswick County-based environmental group, Cahoon made one thing clear: “Let’s get past the idea that it’s harmless.”

He continued, “We’re worried about GenX in our drinking water. It’s toxic. It’s corrosive. We know that.”

What the thousands of Wilmington and Brunswick County residents whose drinking water is contaminated with GenX, Nafion and associated perfluorinated compounds do not know is the health effects of these chemicals within the human body.

“What we haven’t got is a vast set of data yet telling us how it works as a compound,” in humans, Cahoon said. “We don’t know anything about them, but we’re drinking them. I don’t know how you feel about it, but I don’t like being a test subject. These experiments on us have been done without our consent, without our prior knowledge.”

Supporter Spotlight

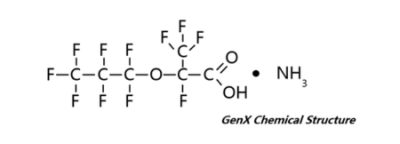

GenX is the commonly used term for perfluoro-2-propoxypropanoic acid, a chemical compound produced to make Teflon, which is used to make nonstick coating surfaces for cookware.

Chemours has been discharging GenX into the Cape Fear since the 1980s.

GenX, like other perfluorinated and polyfluorinated compounds, is poorly studied, generally does not break down in the environment, cannot be removed by most water treatment techniques, can behave strangely in the human body and its health risks are not understood.

There are no federal guidelines for GenX. The North Carolina Division of Health and Human Services has established a health goal of 140 parts per trillion, or ppt.

“Parts per trillion doesn’t sound like much until you do the math,” Cahoon said.

At 140 ppt, that’s 252 molecules of GenX per cell, per liter, he said, which means that every cell in your body has the opportunity to interact with the chemical.

North Carolina State University in Raleigh is conducting a health study of more than 300 Wilmington residents.

This is the first human exposure study, Cahoon said.

That university is also testing treatment systems.

Researchers with UNCW are studying perfluorinated compounds in the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority’s drinking water system.

The North Carolina Division of Environmental Quality, or DEQ, is sampling additional sites and monitoring discharges.

Little remains known about how GenX reacts in air.

Little remains known about how GenX reacts in air.

The revelation that the chemical has been found in honey has Cahoon theorizing GenX is airborne.

“The aerial transport part of this has not been fully studied at all,” he said. “We don’t know how much of that stuff is moving through the air. We know it is. How far down wind does it go? We need basic data. Where’s the stuff showing up? In what forms? This isn’t just a water issue.”

In mid-October, Chemours reported an air leak at its Fayetteville plant where 125 pounds of chemicals related to GenX were released within a time span of 13 hours.

The company, however, failed to report a spike in GenX levels at the wastewater discharge outfall into the river earlier that month.

In all, the plant discharged GenX into the water or air three times in October, the month after a partial consent order signed in Bladen County Superior Court banned Chemours from discharging GenX, Nafion or associated perfluorinated compounds into the river.

Chemours is required to report a spill to DEQ within 24 hours, a stipulation under the company’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System, or NPDES.

DEQ is in the process of revoking the company’s NPDES permit. The permit was partially suspended Nov. 30.

A 60-day notice is required for the permit revocation. The notice expires Jan. 15, 2018, after which time DEQ can take permanent action against the permit.

The Fayetteville plant produces four different sources of wastewater, Cahoon said, so the permit revocation doesn’t necessarily mean GenX and other compounds will not continue to be released.

“I think legitimate discharge for all this stuff is zero,” he said. “We’ve got to make sure that our elected representatives and our state regulators don’t ignore it. We’ve got to make sure they take this seriously.”