Last in a three-part series

Getting to the Three Sisters Swamp to paddle amongst the ancient bald cypress trees is a relatively easy, laid-back trip down the Black River.

Supporter Spotlight

Venturing through the swamp, its watery floor littered with fallen branches, downed logs and fields of cypress knees, is a different story.

Some passages are just wide enough for kayakers and canoeists to slip through. Paddlers sometimes have to push, pull, scoot and rock their way through the intricate swamp forests’ maze.

“You see something different every time you come through here,” said Cebron Fussell.

It was a while before Fussell, leading a group of 10 kayakers and canoeists, most members of the Friends of Sampson County Waterways, spotted a familiar, neon-colored ribbon he uses to mark paddling paths.

Fussell is no stranger to the Black River, having paddled it countless times. It’s hard to imagine traversing through Three Sisters without someone as experienced as him as a guide.

Supporter Spotlight

Three Sisters is about 4 miles down the river from where the paddlers put in at Henry’s Landing, privately owned land opened to those willing to pay a small fee to access the river.

A yard sign, white with black lettering, is staked next to the dirt drive leading from the road to the landing: “NO Black River State Park.”

Those words echo throughout the riverside community, members of whom argue a state park would damage the river’s ecosystem, heighten the trespassing problems in which they deal with, and burden, in some cases, resource-strapped emergency first responders.

Out of the Blue

Riverfront property owners learned about the proposed Black River State Park after it was introduced into legislation earlier this year.

Up to that point, there had been no public meeting, no notice that such a proposal was coming down the pike, property owners say.

“They pushed this through the House without ever coming to this area and having the first meeting,” said Ivanhoe resident Donna Sykes. “I started a petition because the people who do not want a state park in our area are not being heard.”

She’s collected more than 1,300 signatures, names including that of Harold Corbett.

“I’m dead set against it,” Corbett said. “I don’t like the way they went about it. If I hadn’t heard about it from somebody who told me I wouldn’t have known a thing about it. The way they went about it was underhanded. My whole family feels the same way.”

Corbett lives in Atkinson, a small Pender County town near the Bladen County line. He lives closest to the Black River of his siblings, whose family land stretches 3 miles along the river and more than 600 acres in Sampson County.

The land has been in the family for more than 100 years.

They tend to the land and enjoy its natural resources, hunting and fishing off the Black River’s banks.

“I want to be left alone on my property,” Corbett said. “We’ve taken care of it. The state can’t even mow the shoulder road. They want to tell me how to run my own property?”

More people, more problems?

Despite park officials’ assurances that private land would not be taken via eminent domain, riverfront property owners remain leery.

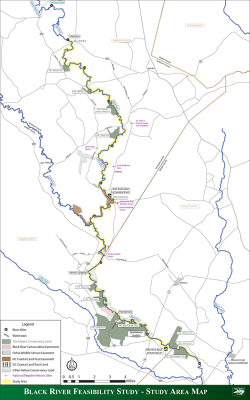

There are only a handful of river accesses, including private property launches, along the nearly 70-mile-long river.

Riverfront property owners interviewed for this story said they do not know how the state intends to add more launches if they do not own the riverfront property necessary to do so.

Avid river paddlers like Fussell would like to see more public river access, but, he admits his feelings are mixed about the prospect of additional accesses drawing more people to the river, particularly Three Sisters.

During a series of state-sponsored community meetings held during the course of the late summer and early fall, parks officials gave a loose estimate that upwards of 50,000 people may visit the river each year.

“This area can no way withstand that many people,” Sykes said.

“Even if you break it down to 140 people a day in that river, you’re going to see a lot of negative impact on the ecosystem, on the wildlife. There’s going to be so much trash. There’s going to be so much trespassing. There is no water rescue here. The Ivanhoe Volunteer Fire Department doesn’t have a boat. There are no restaurants here. We like it like that. It is literally an untouched area. The reason that it’s so beautiful is the lack of people here. We’re happy for people to come visit the area, but we’re not looking to advertise.”

The Sampson County Board of Commissioners in July adopted a resolution in support of the proposed state park, stating a park would allow people to “enjoy this natural resource, promote tourism and economic growth.”

Commissioners in Bladen County, which could host a large chunk of the proposed park, have had little discussion about it, according to board Chairman Charles Peterson.

“I did go to the (state) meeting,” Peterson said. “Personally, I live on the other side of the county, but I’d have to lean toward the people of that community. The more I know about it, I would say I would be against it because I’m not well versed on what’s going to happen down there. It’s a beautiful place. The thing that bothers me about state land is we have thousands and thousands of (acres of) state land in Bladen County that we don’t get tax (revenue) off of.”

Bladen County Commissioner-at-large David Gooden also pointed out that state-owned land equates to no tax revenue.

“In my opinion the state owns enough land in Bladen County,” Gooden said. “And, people in that area do not want it. I know a lot of those people that live down there. They don’t want a bunch of people down there and I respect that.”

Sykes said she hopes Sampson County commissioners will rescind their vote.

“You can get on the river if you want to get on the river and we’re not trying to keep anybody off the river,” she said. “We just do not want them to funnel that many people through this area. I’ve lived here for 40 years and it looks the exact same as it did 40 years ago. The reason is because we’re so rural and so far out. All the neighbors help each other. Most people farm in some way. The cypress trees are already on Nature Conservancy land. Everything is protected. Nobody can log them. You can’t even hardly get to them.”

She said she fears the same for novice paddlers drawn to the proposed park that try to navigate the river and swamps. Cell phone reception is, at best, spotty along parts of the river. If someone gets in trouble, Sykes said, they may not be able to call for help and, if they do, it may take rescuers a long time to reach them.

Sykes’ concerns are a consistent theme among those arguing against the prospect of a state park.

“The point is we don’t want 50,000 people in there tearing this place up,” said riverfront property owner Paul Turlington. “It will destroy it.”

Turlington owns 10 acres just below Three Sisters in Bladen County.

He doesn’t want a park. He doesn’t want any part of the river designated natural area. The option of “nothing” was not available on surveys offered to those who went to the state-sponsored meetings, he said, only what they wanted in a park.

“The Nature Conservancy owns all the land that is important to the trees,” Turlington said.

Rachel Giddens’ family owns a little fewer than 200 acres along the Black River near the South River. Giddens is a blueberry farmer. The land has been in her family for decades.

“The influx of people through here if they open a park, it’s just going to devastate the area,” she said. “The river would change. If those trees weren’t there, I probably wouldn’t be as worried about it. I care about the area. I care about those trees.”

She fears converting portions of the river into state park would change the culture in which her family has a rooted history.

“Our family used to run the steamboats to Wilmington and back hauling supplies,” she said. “We’ve left the riverside natural. It’s everyday life to be on that river, to be a part of that river. We are a part of that river and that river is a part of us.”