BEAUFORT – The University of North Carolina-Institute of Marine Sciences and the town are collaborating on a three-year study that should shine light on how to best manage stormwater to protect the quality of coastal waters, particularly coastal estuarine reserves.

According to Michael Piehler, one of the scientists on the project, the goal is to examine how stormwater flowing from Beaufort affects the Rachel Carson Estuarine Reserve, which includes Carrot Island, Town Marsh, Bird Shoal and Horse Island. The study is funded in part by the National Estuarine Reserve, and the results are expected to be at least partly transferable to other reserves in the national system, particularly those that are near urban areas, as the Rachel Carson is to Beaufort.

Supporter Spotlight

But, Piehler added, the researchers also expect to learn a lot of hard science that could help lead to changes in the way state agencies and others handle stormwater runoff, which is the biggest polluter of coastal waters used by shellfish harvesters, swimmers and boaters.

For example, he said, “We’re looking at the magnitude and pathways of stormwater, including outfalls, in Beaufort,” as well as what is contained in that stormwater.

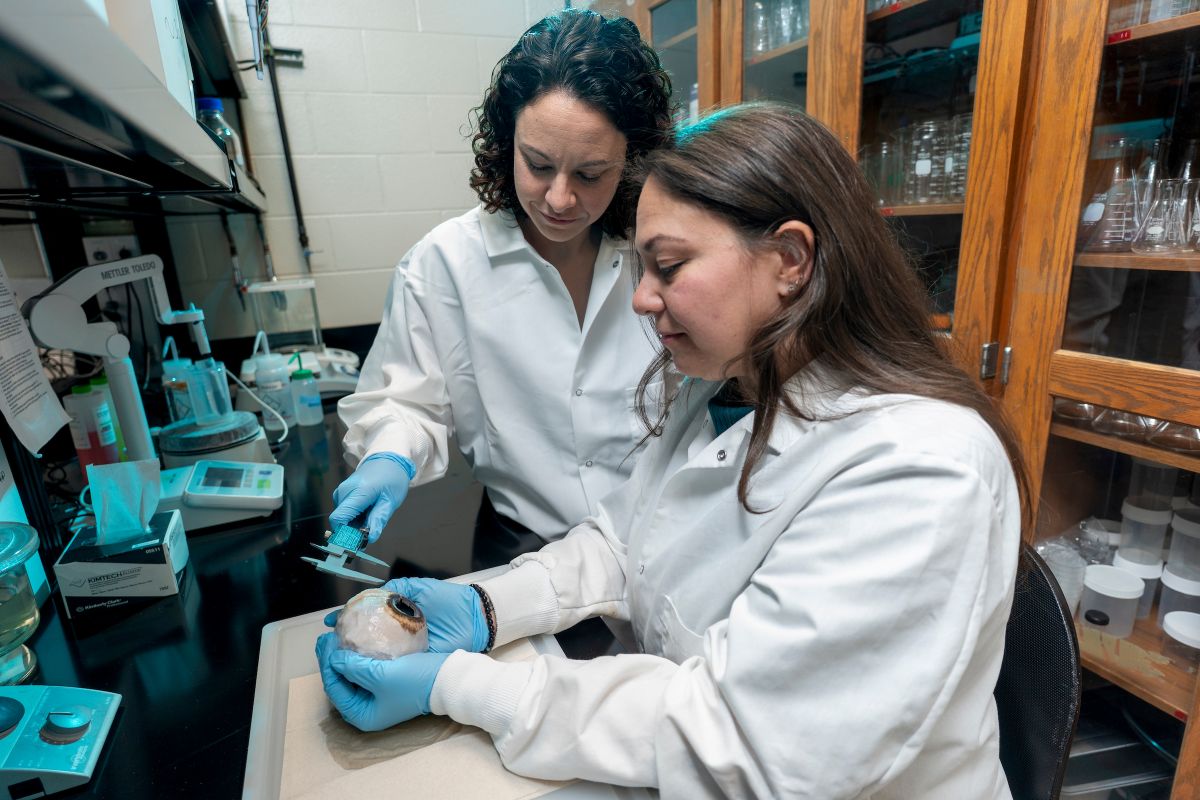

The leader of the project is Rachel Noble, a UNC-IMS professor and researcher considered an expert on pathogens in stormwater. She’s also a Beaufort resident.

According to her lab’s website, “A main thread of Dr. Noble’s work is the application of novel molecular techniques for applied and basic science.” She has developed rapid water quality test methods, including those for E. coli, Enterococcus, and Vibrio species, and studies the dynamics of microbial contaminants contributed through stormwater runoff to high-priority recreational and shellfish harvesting waters. Specifically, the research seeks to separate the pollution from human activity from that already in coastal ecosystems to permit development of accurate models.

Piehler said that although the project is focused on Beaufort and the estuarine reserve, those rapid water quality tests Noble has developed could have practical uses not only there, but elsewhere.

Supporter Spotlight

Currently, Piehler said, methods used by North Carolina and others are slow. In essence, “you often find out that a water body was contaminated two days ago, because of the length of the analysis. If you can speed that up, you have real-time information and you can warn the public faster.”

Even better, he said, the rapidity could enable managers – such as the state Shellfish Sanitation Section of the Division of Marine Fisheries – to open waters more quickly after they’ve been closed because of contamination. And that could apply to shellfish-harvest waters and to recreational swimming waters, both of which are monitored by shellfish sanitation and are economically important to coastal communities and their citizens, as well as the state.

At the very least, he said, he and Noble hope the project can help create better “predictive models” of the effects of stormwater on the waters of the reserve, and elsewhere.

The overall study, Piehler said, involves the setup of six sampling locations, which use automated instrumentation, at known major sources of major stormwater discharge, along Front Street in Beaufort. Two of them are at that street’s the intersections with Orange Street and Gordon Street, and both of those face the reserve, which is just offshore. So, knowing what comes out of those pipes, how much comes out and when the pathogens and sediments come out are keys to protecting the reserve and its fragile water quality. A “control” sampling site is farther away from the town, so the researchers can compare what comes out and into the waters.

One thing researchers have learned in recent years is that the old idea that most pollution in stormwater comes out in the “first flush” – the runoff from the first half-inch or inch of rain runoff – isn’t true, Piehler said. Studies in California, and along North Carolina’s Outer Banks, have shown that pathogens – viruses, bacteria and other potentially harmful micro-organisms – “actually are discharged throughout a storm,” he said, a finding that throws a bit of a monkey wrench into the design of some stormwater ponds that have been used for years to hold runoff so it settles and gets “natural treatment” before flowing to rivers and streams and sounds.

The recently acquired knowledge, Piehler added, also gives increased credence to efforts by the North Carolina Coastal Federation and others to intercept and hold polluted stormwater closer to its source, through use of things like rain barrels and rain gardens.

“The Coastal Federation is touting some successes with those efforts,” he said, “and we’re interested in working more on determining how you ‘gauge’ success.”

The concept of “flow reduction farther up in the watershed” does make sense, he added, as it’s better to catch pollutants before they get anywhere near the streams. And one of the most important pollutants to catch early is nitrogen, which probably does the most harm to coastal waters because it stimulates growth of algae that robs the water of oxygen when it breaks down. Even most treatment plants struggle to adequately remove nitrogen.

Piehler said the study has a large educational component, too, working with students at Beaufort Middle School, among others, to teach them about stormwater and its effects on the waters around them, It’s similar to what the federation does – helping students build rain gardens while also generating the next generation of dedicated stewards of the coastal environment.

Noble said Beaufort and other mid-sized coastal towns are at an ever-increasing risk for polluted stormwater problems, as well as flooding, because of a variety of factors, including old infrastructure and development and sea-level rise, which creates higher tides that can flood roads, such as Front Street. That means the tides essentially “push back” against the stormwater, leaving it no place to go. The result can be more polluted stormwater in the streets. Folks who have lived in Beaufort for a long, long time, Noble said, are occasionally seeing floods at times, and in places, they’ve never seen before.

High groundwater levels exacerbate the problem, as the stormwater on the land can’t soak in as quickly, so the land is less able to provide cleansing of the stormwater’s pollutants.

All of this means that stormwater control is increasingly difficult along the coast, especially in the urbanized areas like Beaufort, and these places are going to have tough choices to make, choices that are going to cost money. Technological solutions are expensive, especially when you’re talking about stormwater flows that can reach thousands of gallons per minute, Noble said.

That’s where landscaping solutions – like those preferred by the federation – can be among the most cost-effective.

Another aim of the study, according to Piehler and Noble, is to come up with specific recommendations on how Beaufort can address the problems. Is flooding the major issue, or is it runoff? And where are the major problem areas? And how do those problems, and solutions to those problems, affect the reserve.

Beaufort Planning Director Kyle Garner said he thinks the study will be beneficial to the town, especially any suggestions on what can be done and how to prioritize them.

“If that happens, it’s a win-win,” he said. “We know that when you talk about stormwater problems, it’s not just the quantity, it’s also the quality.”

Garner said the town does have a lot of old infrastructure, and has been working diligently on stormwater issues. The town has staff dedicated to the task of maintain and improving ditches and creating rain gardens and bio-retention areas.

“I think the things we have done have already made some difference,” he said. “The past few heavy rain events that we’ve had, we haven’t had as many problems as we sometimes did in the past.”

The town is working with the federation to develop a watershed management plan, a move other towns have already undertaken. For example, Swansboro did one with the federation, which was approved in February. The town had previously implemented a stormwater fee that applies, to varying degrees, to all developed residential and commercial properties.

For residential property owners, the fee is based on a structure’s square footage, and range $2 per month, or $24 a year, to $3 a month, or $36 a year.

The commercial fee ranges from $10 a month, or $120 annually, to $50 a month, or $600 annually, depending on the area of impervious surface on a property.

Revenue goes to an enterprise fund dedicated to stormwater management needs, including paying for construction, replacement, repair, improvement, maintenance, operation and use of ditches, pipes, drains and other methods to control runoff.

Garner said Beaufort officials believe a watershed management plan will be very helpful, and could even lead to increased chances of getting grants from state agencies, such as the Clean Water Management Trust Fund. The town has a stormwater fee for all residential properties of $4 per month, paid on the tax bill at the end of the year, but doesn’t have one for commercial developments. A plan, he said, could help Beaufort get a handle on how a commercial stormwater management fee might look.

The town also has a stormwater advisory committee, which meets regularly, and includes members with a lot of expertise.

Noble is on it, as are, among others, Carolyn Currin, a coastal and estuarine ecologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Beaufort Laboratory; P. Lee Ferguson, an associate professor of civil engineering at Duke University, which has its marine laboratory in town; Whitney Jenkins, coastal training program coordinator for the North Carolina Coastal Reserve and the National Estuarine Research Reserve; Robert Safrit, a landscape designer; and Tommy Simpson, a building contractor.

The town, Garner said, takes stormwater issues seriously, and wants to continue to make improvements.

The problems surface most noticeably when tides are high, he said, as Noble mentioned. But there are some areas that aren’t affected by tides where problems still occur.

Again, though, he said, “We are always working on those areas, trying to provide areas for more (stormwater) storage capacity.”

Jenkins, the Beaufort Stormwater Advisory Committee chair and the coastal training program coordinator for the North Carolina Estuarine Reserve and National Estuarine Reserve, hailed the collaborative nature of the study. In fact, she said, it’s required by the grant provider, the National Estuarine Research Reserve System, or NERRS, Science Collaborative, which collaborates with others who have stakes in the efforts. It’s not, she said, supposed to be science “in a bubble.”

“It’s all come together very well,” she said of the study. And while she said she doesn’t see “plumes” of polluted stormwater headed to the reserve on a regular basis, she knows there are plenty of sources.

“There are the town docks, where we are not sure everyone uses pump-out facilities,” she said. “There is the town’s wastewater treatment plant outfall, which we know works well but can have breakdowns. There are kayakers, and field trips to the reserve by students and other visitors. There’s a lot of potential exposure to pollution.”

What’s good about the study, she said, is that it’s comprehensive, and pro-active: It doesn’t look just at where the storm water comes from, but will offer ideas on how to reduce it, and its impacts, with involvement from many players, including the town, the university and the state shellfish sanitation agency.

Jenkins agreed with the need for faster testing, analysis and actions to close and open waters when pollution is detected.

Shellfish sanitation doesn’t regularly sample Taylor’s Creek, she said, as it’s closed to shellfishing because it’s polluted. And though the agency does sample it for recreational purposes, that’s on a set schedule. Faster sampling and analysis, she said, would benefit all.

Piehler said he can’t yet quantify the problems at the monitoring sites, but expects to have some answers by the end of the summer.

“We really just got started,” he said. “We’ve been ‘tuning’ the instruments,” he added, and really just started getting samples from them last week.

But by the end of the year, he added, all involved should have a better understanding of how stormwater affects the reserve, and Beaufort should be on the way to getting some answers of its own.

Noble agreed.

“I think the study is going very well,” she said. “We’re doing some important work, we have great team members onboard and people are excited.”