WILMINGTON – Like a general rallying troops before war, environmental advocates made clear the fight against seismic testing in the Atlantic may be tough, but winnable.

“The battle for the Atlantic has begun and we are going to win this battle,” said Randy Sturgill, the Southeast campaign coordinator for Oceana, a national conservation group that has been among the leaders in the fight against offshore drilling in the mid-Atlantic. “This one is really going to take you getting down and really getting into the trenches and fighting. What we want to do is ignite that here tonight. Welcome to the fight.”

Supporter Spotlight

Sturgill led off a meeting Tuesday hosted by various environmental groups hoping to garner residents throughout the Cape Fear region to form a citizen-based group opposed to offshore drilling following President Donald Trump’s reversal of the federal government’s denial of six seismic testing permit applications.

Their first order of business: write the National Marine Fisheries Service, or NMFS, about the negative effects seismic air gun blasting may have on marine mammals. The agency reviews all proposed seismic activities for incidental “takes” — the inadvertent harming, killing, disturbance or destruction of wildlife — anticipated during such testing.

On Monday, NMFS opened a 30-day public comment period on incidental harassment authorizations, or IHAs, which regulate the number of “takes” of marine mammals allowed during seismic testing.

Mike Giles, a coastal advocate with the North Carolina Coastal Federation’s southeast regional office, called the 91-page notice “complex.”

The federation, along with the other environmental organizations that hosted the Tuesday night event, including Oceana, and the local chapters of the North Carolina Sierra Club and Surfrider Foundation, is offering to help residents who want to comment on the proposed assessments.

Supporter Spotlight

The meeting, which drew more than 100 residents, including members of various community organizations such as the recently formed Brunswick Environmental Action Team, or BEAT, was the first in what is expected to be a series of informational meetings about the potential environmental and economic impacts of seismic testing.

For many in the large meeting room of the New Hanover County Northeast Regional Library, this ensuing fight will be the second time around.

Several people indicated they were part of a collective voice of opposition that arose in 2013 after the Kure Beach mayor at the time signed an oil industry lobbying letter supporting testing for offshore oil.

It was a move that marked the southern North Carolina coastal area as the ground zero of a public uprising against offshore drilling, one Sturgill calls the “homegrown resolution revolution.”

In 2016, Kure Beach, led by a new mayor, became the 100th municipality to oppose offshore oil drilling.

In all, 125 communities up and down the East Coast have passed similar resolutions opposing offshore oil and gas exploration and drilling.

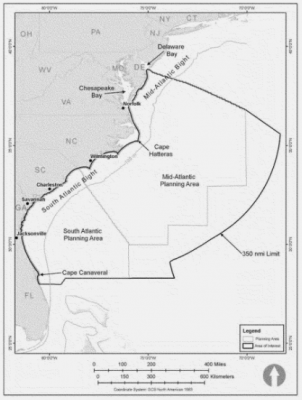

Environmental advocates say then-President Barack Obama listened to that opposition, ordering the U.S. Department of Interior in January to deny all six applications from seismic testing companies aiming to test for oil and gas reserves within the Outer Continental Shelf.

On May 10, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke signed an order forging ahead Trump’s agenda to explore energy resources in the Atlantic.

The 50-mile buffer from the coast established during the Obama administration no longer exists.

This means testing could take place “within earshot” of coastal residents, Giles said.

Seismic testing uses air guns towed behind ships to send sonic waves that penetrate the ocean floor. How those waves are reflected from the bottom gives hints to the location and extent of oil or natural gas deposits below the surface.

The controversy around these tests is that the use of sound may disturb the normal behavioral patterns of marine mammals such as right whales and dolphins.

The background noise created from the blasts make it harder for marine mammals to hear each other, their young and predators, according to marine mammal scientists. This noise disrupts communication, may cause physiological distress, alter the animals’ migration patterns, their feeding and reproduction.

“This seismic testing, it happens 24 hours a day, just about all year,” Giles said. “It’s constant. This is just a bad idea. They’re going to continue to blast these seismic air guns over and over and over again up to two to three years.”

If granted, the current applications would allow vessels that conduct seismic testing to overlap testing areas, which means testing would be conducted in the same areas multiple times, increasing further the number and duration of blasts, opponents say.

Commercial fishing, ocean-dependent tourism, and commercial shipping and transportation will be impacted by seismic testing, Giles said.

“The costs are great,” he said. “What do we want our coast to be? That’s the question we’ve got to answer. If they drill, they will spill, and the costs are too great for our coasts.”

Doug Wakeman, a retired professor of economics at Meredith College’s School of Business, and member of the federation’s board of directors, briefly addressed the 2013 report Quest Offshore Resources Inc. of Texas prepared for the American Petroleum Institute and National Ocean Industries Association.

The Quest report forecasts North Carolina would benefit the most in the oil and gas industry jobs – a projected 55,000 by 2035 – of any state along the Eastern Seaboard with an estimated $4 billion increase in economic activity.

The report doesn’t take into account the current price of oil, which has significantly dropped since the report was compiled, Wakeman said.

“I think we can charitably call it propaganda parading as science,” Wakeman said of the Quest report. “Basically you can take anything in that report and disregard it.”

That’s just what residents like Bruce Holsten plan to do.

Holsten, chairman of the Cape Fear Economic Council, was one of a handful of residents who volunteered at the Tuesday night meeting to take on leadership roles, helping offshore drilling opponents organize and write letters to their local, state and federal representatives.

“This is an economic issue, big time,” he said. “We’ve got to stop that blasting. You stop the blasting, nothing happens.”