Last in a series

JACKSONVILLE – After seven major hurricanes affected North Carolina’s coast during the 1950s, the state responded by tightening coastal building regulations.

Supporter Spotlight

It was a decade of storms the likes of which included Hurricane Hazel that hit the North Carolina coast in October 1954, churning up a storm surge recorded at 18 feet at Calabash and packing wind speeds of 150 mph on Holden Beach.

Hazel was a reminder of how vulnerable coastal structures on barrier islands are during storms and, in the mid-1960s, the North Carolina Building Code Council adopted specific hurricane-resistant rules for small residential buildings on the state’s barrier islands.

It’s still too soon to know what, if any, regulatory changes may come of the lessons learned from Hurricane Matthew in October, but the implementation of more stringent building codes for coastal structures is just one example of post-hurricane-related actions taken by government in the past to minimize destruction along North Carolina’s 300 miles of coast.

Over the years, some beach towns have amended their local ordinances that require setbacks farther than state rules pertaining to frontal dune systems. Some, like Topsail Beach, have restricted the amount of sand that may be moved from secondary, or farther inland, dune systems. Many coastal towns that have incorporated routine beach nourishment programs are touting the benefits sand reinforcement has in protecting landward structures against storms.

Coastal planning experts say that great strides have been made in reducing storm risks, but there’s still a way to go.

Supporter Spotlight

“I think there are a number of things that communities have been learning,” said Jim Schwab, manager of the American Planning Association’s Hazards Planning Center. “Hurricane Sandy certainly revealed a lot of things to us.”

Hurricane Sandy made landfall north of Cape Hatteras on Oct. 29, 2012, and barreled up the East Coast, pummeling heavily populated, urban areas in the north.

Since then New York City, with its densely developed waterfront areas, has taken on the challenge of redesigning buildings that meet zoning height restrictions while, at the same time, elevating those buildings to comply with national flood insurance program rules.

“There are design solutions for all of that,” Schwab said.

North Carolina’s coastal communities do not have the same population, but the state’s coastal communities can learn from the planning practices New York City is putting into play.

One of the ways beach counties and towns are doing that is by tapping into a resource designed to aid in storm mitigation planning.

Digital Coast, a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration-sponsored website, has become a popular coastal management tool among coastal counties and towns throughout the country.

“Among the things available in there are a number of mapping tools to help communities identify things like coastal habitat areas, sea level rise and visualization tools so you can look at projected sea level rise,” Schwab said.

The idea is to make the job of planners in coastal areas easier.

In anticipation of rising sea levels as a result of climate change, some coastal communities have chosen to respond to post-hurricane lessons by taking steps including acquiring flood-prone properties and adopting freeboard requirements, Schwab said.

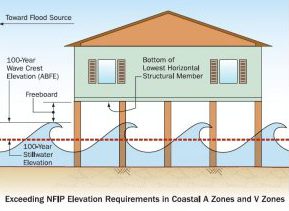

Freeboard is a margin of safety from elevating a building above the National Flood Insurance Program’s minimum height requirements set by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA.

There are multiple benefits for towns that adopt a foot or more of freeboard, including flood insurance discounts for the homeowner, greater protection against sea level rise, and decreasing the chances of flood damage in a storm.

Beach communities in North Carolina, including Topsail Beach and Ocean Isle Beach, have in recent years adopted a 3-foot freeboard requirement. About half of the coastal communities in the state have adopted at least 2 feet of freeboard.

The benefits of raising homes on barrier islands have been documented since the state’s building codes for beach structures were added in the 1960s.

Topsail Island was left in shambles in 1996 when Hurricanes Bertha and Fran delivered a one-two punch.

More than 100 homes with shallow piling foundation systems collapsed along the 26-mile-long island, according to a 1997 FEMA Building Performance Assessment.

Despite the massive destruction left in the wake of Hurricane Fran, the FEMA report found that the state’s tighter building codes on barrier islands had made a difference.

FEMA’s assessment concluded that of 205 oceanfront structures built on Topsail Island after 1986, more than 90 percent sustained no significant foundation damage.

“The shift in State Building Code to require longer pilings for erosion-prone buildings along the ocean was generally successful,” according to the report.

Another success borne from post-hurricane lessons is the state’s floodplain mapping program, Schwab said.

The state in 2000 undertook a nearly decade-long process of remapping the state’s floodplain areas in the wake of Hurricane Floyd. The mapping system is available to the public in digital form and it provides an array of information that includes flood forecasts for land, roads and bridges.

“It’s certainly one of the best in the country,” Schwab said. “In a way it does help provide and disclose the vulnerability of different coastal structures in communities. “

Gavin Smith, a research professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s department of city and regional planning, agrees, saying that the state’s floodplain mapping program is an “amazing tool” created, in essence, as an outgrowth of Hurricane Floyd.

“On the other hand, there’s intensive growth pressures in the coastal zone,” said Smith, who is also director of UNC’s Coastal Resilience Center, one of 11 Department of Homeland Security centers of excellence, and a member of the APA’s Hazard Mitigation and Disaster Recovery Planning Division.

“There has been a push in the past four or five years to downplay the changing climate,” he said. “As we move into an era of climate change that is a real problem.”

Local governments are required to provide hazard mitigation plans, but few of them look at land-use rules as a tool to limit future risks, Smith said. And, few of those plans address climate change, he said.

“I think there’s some real progress, but we still have some real challenges of local governments making strides in hazard mitigation,” he said. “We still have a lot of work to be done.”