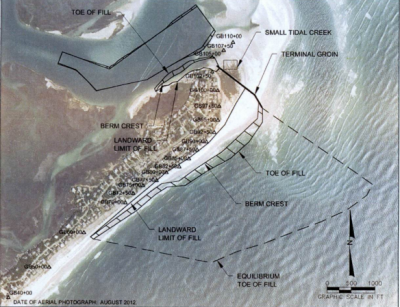

FIGURE EIGHT ISLAND – The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been given more time to analyze the effects the proposed terminal groin for Figure Eight Island may have on federally listed species.

This is the second time in recent months that the Fish and Wildlife Service has asked the Army Corps of Engineers for an extension. The agency wants to further study what effects a proposed 1,500-foot-long terminal groin at the north end of the private island will potentially have on threatened and endangered species, specifically, little shorebirds known as piping plovers.

Sponsor Spotlight

The agency’s request to push back its deadline for submitting a biological opinion on the proposed project was granted by the Corps on Oct. 14.

A biological opinion is part of a process known as Section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, where federal agencies consult with one another to conserve threatened and endangered species. A formal consultation between Fish and Wildlife officials and the Corps ensues when a determination is made that a federally funded or permitted project is likely to adversely affect a listed species.

In this case, Fish and Wildlife officials want more time to analyze the documented populations of piping plovers, including those within the endangered Great Lakes population, at the north end of the island.

Kathy Matthews, a fish and wildlife biologist in the service’s Raleigh field office, said the agency received new information sometime around July about piping plovers on the island’s northern end.

Sponsor Spotlight

That information included more documented sightings of banded piping plovers than initially received, she said. Small, colored bands placed on a bird’s leg help wildlife biologists track a bird’s place of birth as well as its migratory patterns.

“We received additional data that added more dates of sightings and things like that,” Matthews said. “It was more than we realized and that’s based on sightings from several different folks. We had to step back and make sure we had the best available information. We’re just trying to use the best information that we can to write the biological opinion.”

She declined to discuss exact numbers.

“I don’t really want to quote a number right now,” she said. “It depends on the year. It depends on the date. It is a little bit complicated.”

Lindsay Addison, a biologist with Audubon North Carolina, said that the organization this fall has recorded 36 piping plovers in a survey at Rich Inlet. That number does not indicate the total number of piping plovers using the site in a given year or season because the birds migrate throughout the spring and fall.

All three populations of piping plover, including those of the Great Lakes, Atlantic Coast and Northern Great Plains, have been documented at the island’s north end.

“We’re concerned about all three, of course,” Matthews said. “We have to analyze all three.”

The Great Lakes piping plover population was listed as endangered in 1986. That same year, the government listed the Atlantic Coast and Northern Great Plains populations as threatened.

There are only about 75 breeding pairs in the Great Lakes population, Addison said. Almost that entire population is banded and Audubon’s surveys here have in the last five years counted at least 28 birds from that population, she said.

In addition to other shorebirds, including least terns, piping plovers use the acres and acres of barren sand and shoals on the banks of Rich Inlet for nesting, resting and eating. The area is federally designated critical habitat for the Great Lakes and Atlantic Coast piping plover populations.

“The counts that we’ve been doing show that Rich Inlet continues to provide high-quality habitat for piping plovers, and they are continuing to depend on it this fall,” Addison wrote in an email.

Rich Inlet supports more piping plovers than any other inlet in the region, including Topsail, Mason and Masonboro inlets, she said.

Environmental groups and conservationists opposed to the terminal groin say land north of the structure will erode away within a few years after the groin is built. That’s also a projection made in an environmental study of the project.

Proponents of the terminal groin argue that the inlet will eventually migrate in a direction that would, without a terminal groin, erode the northern end.

The proposed project, which would include periodic beach nourishment, which will cost an estimated $23.5 million over 30 years, according to the project’s final environmental impact statement.

Each property would be assessed a fee to cover the costs.

Figure Eight Island property owners have until the end of this month to cast their votes in favor of or opposition to the terminal groin.

Under the Figure Eight Island Homeowners Association’s restrictive covenants, only one person per property is allowed to vote. There are 563 lots on the exclusive island in New Hanover County.

At least 48 property owners representing more than 25 properties went on the record opposing the terminal groin. Those property owners support an alternative shoreline erosion control method that would maintain the bar channel of Rich Inlet in a position closer to the north end of the island.

Depending on the outcome of the vote, the association’s board of directors must obtain several property easements before the project can move forward.

The terminal groin, a wall-like structure usually made of rock and steel built perpendicular to the shore, would cross upwards of 12 to 15 properties at the north end.

At least a few owners of those properties have said they will not grant an easement to their land.

Because Figure Eight Island is private and not an incorporated community, the board of directors does not have the authority to take land easements through condemnation.

Per state law, a Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA, major permit application must include a copy of the deed “or other instrument” claiming title to the property.

Until that permit is approved, the Corps can’t move forward with a federal permit.

“Even if I did have something in hand from Fish and Wildlife Service and were looking at authorizing the work, and we haven’t made that decision, I still have to have the CAMA permit,” explained Mickey Sugg, a project engineer with the Corps’ Wilmington district.

Since it’s unlikely the state would have an answer on a CAMA permit by Dec. 16, which is the new deadline for the biological opinion, the extension has no bearing on the proposed project.

“All it really means is we won’t receive a response from fish and wildlife service until December 16,” he said.