First of two parts

BEAUFORT — The products of North Carolina’s estuaries are found on dinner plates up and down the East Coast. Peek into a restaurant in New York, and you may see a blue crab that once lived in the sea grasses of Bogue Sound. Stroll into an oyster bar in South Carolina, and you may dine on oysters harvested from Pamlico Sound. Many of the creatures that make up North Carolina’s fishing industry at some point in their lives, depend on the humble, shallow waters of an estuary — waters that are facing increasing pressures from human activities.

Supporter Spotlight

This week is National Estuaries Week, as designated by the nonprofit group, Restore America’s Estuaries. In this two-part series that begins today, we will explore what estuaries are, the role they play in the state’s economy and environment, the problems they face and their future.

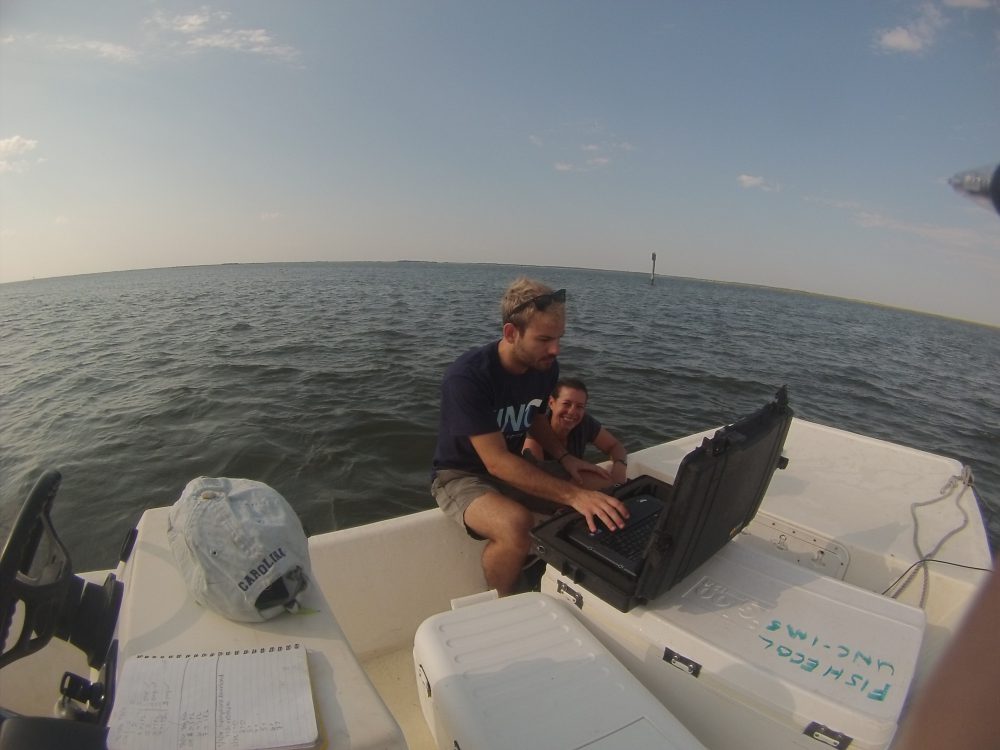

Danielle Keller, a doctoral candidate at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City, studies these unique areas. On a cool summer morning, she’s releasing flounder into the estuarine waters near the Rachel Carson Reserve, across Taylors Creek from the Beaufort waterfront.

As she tosses in the first flounder, Keller points out a small, red surgical spot on the juvenile fish. She explains she’s implanted tracking devices in 20 flounders and 20 gag groupers, and will follow their movements as they travel through the estuary. She is hoping to understand what changes in estuarine sea grass habitats, which are influenced by water quality and climate change, will have on local fish populations.

Studying these waters, she said, is important, because our health is linked with the health of estuaries.

“Everyone is in some way connected to the ocean,” Keller said.

Supporter Spotlight

What are estuaries?

Estuaries are shallow, partially enclosed areas usually found in sounds, inlets or bays. The freshwater flowing to the sea from inland rivers mixes here with the salty ocean, creating brackish waters. Their shallow nature creates the ideal environment for marine grasses and plants that can easily capture sunlight. On this day, the deepest waters Keller wades in only reach her chest.

One of the nation’s largest estuarine systems is found here in North Carolina in the Albemarle-Pamlico region that includes Core, Croatan, Back, Bogue, Currituck and Roanoke sounds.

There are probably few places on earth as productive and mysterious as estuaries. On any given day, these shallow, productive areas appear calm and quiet. However, below the water’s surface, estuarine systems are teeming with organisms ranging from worms, rays, baby fish and shrimp. Species including red drum, black sea bass and stone crabs rely on the habitats within estuaries.

According to the Fish and Wildlife Service, about 90 percent of commercially important fish in North Carolina live in estuarine habitats, such as mud flats, salt marshes and the water column itself, at some point in their lives.

“Every parcel of water, every acre of habitat out there is valuable to some species,” said Joel Fodrie, a professor at the institute who studies estuaries and is also Keller’s faculty adviser.

North Carolina’s estuaries

North Carolina’s estuaries are particularly notable due to their size and biodiversity.

Fodrie said warm water coming up from the Gulf Stream mixes here with the colder waters of the Labrador Current to create a unique environment. The result of this is a variety of species, including the sea grass Keller studies.

Eel grass, a northern species that likes cooler waters, has its southernmost range in North Carolina, and shoal grass, a southern species that prefers warmer waters, has its northernmost range here, too.

Keller is observing to see if animals use the two grasses differently, and if any shift in the grasses’ ranges would affect the animals. This is especially concerning as the range of eel grass may pull out of North Carolina as waters warm because of climate change.

That’s not the only reason why the state’s estuaries are unique.

North Carolina has more sea grass than all other East Coast states, except Florida, combined. It is also home to the Albemarle-Pamilco estuary, which is the second-largest system in the lower 48 states. The area is one of the only remaining places the endangered Atlantic sturgeon still goes to breed annually.

“North Carolina is just replete with resources and issues to consider our role, the role of estuaries, and our balance with estuaries,” Fodrie said.

Congress in 1987 established the National Estuary Program as an amendment to the Clean Water Act after the importance of estuaries was realized. The non-regulatory program created 28 regional organizations across the country. In North Carolina, the Albemarle-Pamlico National Estuary Partnership, or APNEP, was created to research, restore and protect the area.

In addition, the North Carolina National Estuarine Research Reserve was created through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the state to protect more than 10,500 acres across four sites in Currituck Banks, Rachel Carson Reserve, Masonboro Island and Zeke’s Island.

The North Carolina Coastal Reserve, managed by the state’s Division of Coastal Management, protects six more sites, including Bird Island in Brunswick County and Permuda Island in Pender County.

What do estuaries provide?

Summing up the importance of estuaries is not an easy task. They provide a variety of “ecosystem services,” according to Keller, or resources important to both humans and wildlife. Fodrie said their role is extensive, from nutrient cycling to fish production to wave-energy absorption.

The list goes on.

One of the most important services estuaries provide, in terms of the state’s economy, is as a nursery to marine life, promoting the state’s $1 billion fishing industry.

“All the birds that you enjoy looking at when you’re on your boat, all of the fish and crabs,” Keller said, “all of them really grow up in the estuaries.”

The fish Keller studies, gag grouper and flounder, are born in estuaries and take refuge amongst the sea grasses and gentle waters. Keller says one reason for estuaries’ popularity with wildlife is because the area is full of the nutrition larger organisms need to survive, including phytoplankton.

“There’s a lot of food at the bottom of the food chain that other baby fish and crabs can consume,” Keller said.

She added that estuaries are just as productive as rainforests with a variety of habitats and species that call them home. The waters are so nutrient-rich that taking pictures underwater is virtually impossible during Keller’s day of field work, with green phytoplankton creating murky waters.

“People don’t realize that because they don’t see it, essentially because it’s all underwater,” Keller said. “But, estuaries have so many different habitats and provide homes for so many different organisms.”

Habitats like oyster beds and sea grasses filter the water, keeping it clean and fresh for humans and marine life. An oyster can filter water at a rate of up to 50 gallons per day. The areas, along with salt marshes, also buffer storm surges and stabilize shorelines as the spiky beds absorb wave energy.

Estuaries also serve in the frontlines against climate change.

Ian Kroll, another doctoral student at the institute who joined Keller on the water, said estuaries are also known to store carbon. The plants that call estuaries home photosynthesize, meaning they absorb carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas. Over time, these plants die and are covered by sands, along with the carbon they absorbed.

“Instead of coming back to the atmosphere,” Kroll said. “It floats to the bottom of the ocean, deposits there and builds up.”

Fodrie said the unique nature of estuaries is what makes them special.

“Estuaries are just tremendously important both because people are living right around the edge of estuaries,” he said, “but also because they’re pretty dynamic given their nature and the interface between and land and sea.”

To Learn More

Wednesday: Threats facing our estuaries