TRENTON — Solar power and agriculture may not seem related, but in coastal North Carolina, the two are becoming intertwined as an increasing number of farmers lease their land to solar developers. This trend, which provides economic benefits for the farmers, has communities and some state officials worried about the potential environmental and agricultural effects.

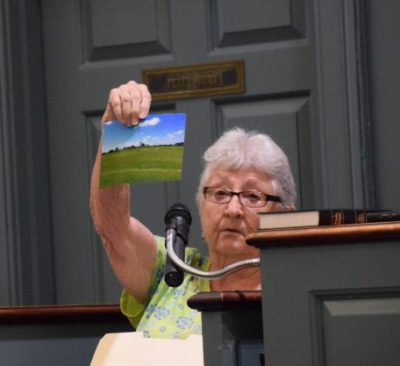

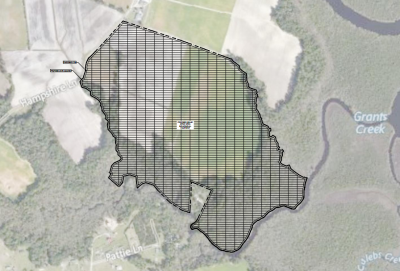

The issue came to a head last week in a courtroom in Trenton in Jones County. About 25 residents gathered for a hearing organized by the North Carolina Utilities Commission for a proposed five-megawatt solar installment between Mallard Cove Landing Road and Trent Farm Road.

Supporter Spotlight

Most who spoke during the hearing were opposed.

“People do not want to live next to something that looks like a prison,” said Andy Gower, who lives near the proposed site.

In addition to the aesthetics, nearby residents said the project could affect their property values and possibly their health, but Douglas “Doug” Soltow, who owns the land where the project would go, said the concerns weren’t real and that he still hopes to profit from solar.

“It’s hard to stop progress, you’ve got to have progress,” he said.

Soltow plans to lease his land to Strata Solar, a Chapel Hill-based developer. According to the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, there are more than 550 megawatts of energy being produced by 402 solar systems in Eastern North Carolina. About 85 of these developments are utility scale, producing five megawatts or more of power, as proposed for Soltow’s land. The number of these particular developments is expected to increase with new proposals popping up on agricultural land in coastal counties including Onslow and Pender.

Supporter Spotlight

A megawatt is a million watts of electricity. That’s enough to power 750 to 1,000 average houses.

New Source of Income

A farmer’s motivation for leasing land for solar development is fairly simple: Leasing can be more lucrative and stable than farming, with less expense and labor. However, like any development, solar installments are subject to oversight and regulation, and they often spark controversy.

For some farmers, the economic incentive of solar is too good an option to pass up.

“It’s a business,” said Soltow, who would not say how much he would make by leasing his land for solar, except that it would be more than he makes from farming. Life as a small farmer is uncertain, he said.

“A lot of small farmers go under,” he said.

One reason for the rise of solar in North Carolina is the state’s Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Portfolio Standard adopted in 2007, which requires that 12.5 percent of the state’s energy needs must come from renewables. Under this standard, Duke Energy and other power companies must source energy from renewable sources in order to receive state incentives.

In response, private developers began building large-scale solar developments and selling the energy back to utilities, including Duke Energy.

Soltow said he still intends to continue with agriculture on part of his land, but that leasing the remaining portion to solar provides financial stability crops can’t.

For solar developers, agricultural land is ideal. Cody Shadley, a project developer at Pine Gate Renewables, which is working on two sites in Onslow County, said agricultural land is ideal because it tends to be cleared of trees, away from floodplains and flat.

“Land that is high, dry and flat, that makes a pretty good foundation for a solar farm,” Shadley said.

Guido van der Hoeven, a senior professor and extension specialist in the Agricultural and Resource Department of North Carolina State University, said he’s heard it’s possible for farmers to make $750 to $1,400 an acre leasing solar. Harvesting crops such as soybean or corn can yield much lower, or even negative, returns.

“They may think it might be worth taking 20 acres or 30 acres, or whatever, out of crop production to ensure that (they) have an income stream of the lease rate for solar,” Van der Hoeven said.

Peter Ledford, a policy director with the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, said that many of the proposals on farmland are five-megawatt farms, as opposed to smaller ones, because the leases last a long time and provide a longer period of stable income.

“The solar developer generally enters into a lease anywhere between 15 and 30 years,” Ledford said, “and the guaranteed income stream for that to the farmer exceeds what they might be able to make from growing crops on their land, or they just want to diversify that guaranteed income.”

There are other benefits for farmers. Soltow, for example, said he will have to do very little to manage the property.

Shadley of Pine Gate Renewables said the company takes care of the operations, maintenance and cleanup of the solar farms, and that representatives drop by once or twice a month to inspect the sites.

“We’re consistently monitoring the project, the life of the project, up until it gets to the decommissioning of the site,” he said. After which, he said, the panels will be removed by the company and the land will be returned to its tillable state if the lease is not extended.

Agricultural, Environmental Effects

Various state agencies must weigh in during the permitting and processing of solar farm applications. The permitting process can take years, depending on the number and kinds of permits needed. Soltow said he’s been waiting a year and a half.

Pine Gate Renewables has proposed a similar project near Maysville in Onslow County. As part of the state clearinghouse process for the Utilities Commission’s approval, a copy of the plan was passed to the North Carolina Department of Agricultural and Consumer Services. In a letter, the department stated concern about the loss of productive farmland to development of any kind.

Joseph Hudyncia, the department of agriculture’s director of environmental programs, wrote the letter. He said in an interview that the loss of agricultural land in North Carolina was “alarming,” but noted that farmers may need to lease parts of their land for solar to make a living.

“Some farmers have gone that route and it’s worked out well for them as a form of diversification,” he said.

Hudyncia added that the solar industry had been receptive to working with other groups. The North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association and the department of agriculture are collaborating on a report that will show that solar has removed only about a tenth of 1 percent of the state’s agricultural lands.

That fraction may not grow too much larger. Van der Hoeven said developing solar on many agricultural lands could be difficult, as transferring the energy to the power company’s grid requires infrastructure that isn’t available in many rural areas.

The state Wildlife Resource Commission expressed fears about how utility-scale solar developments affect wildlife and habitats. Some Trenton residents shared similar worries.

“In general, the NCWRC supports solar facilities located in open areas,” according to a letter signed by Maria Dunn, a coastal habitat coordinator with the commission. “However, the conversion of forests and wetlands to support solar development is causing increasing concern due to the loss of wildlife habitat, the fragmentation of wildlife habitat, and vegetative manage needed post-conversion for wetland and other forested areas.”

Dunn said in an interview that those worries extend to any kind of development, although she added that for solar, agricultural land is preferred to property that hasn’t been cleared.

Shadley agreed, noting that Pine Gate Renewables also prefers agricultural property for the same reason.

Shadley said Pine Gate Renewables follows management practices designed to protect the coastal environment. The company follows guidelines and suggestions recommended by state agencies and also reaches out to communities to address their concerns.

“We want to be a good neighbor; we’re not trying to rock the boat,” Shadley said. “We want to add value to the community.”