Like father, like son.

When Charles Pilkey was a young boy, his father, Orrin, a famous geologist and coastal researcher at Duke University, would take him and his four siblings to Shackleford Banks, an uninhabited island in the Cape Lookout National Seashore. It is there, Charles said, that he first fell in love with the ocean, a love he shares with his father.

Supporter Spotlight

Today, Charles is a 59-year-old sculptor and former geologist living in Mint Hill, near Charlotte. Orrin, of Durham, is 81 now and retired. Charles recalled days spent on the island, where he would wade into tidal pools teeming with snails and small fish, touching and learning first-hand about the natural beach. He said his father instilled in him an appreciation for science and the natural world at a young age.

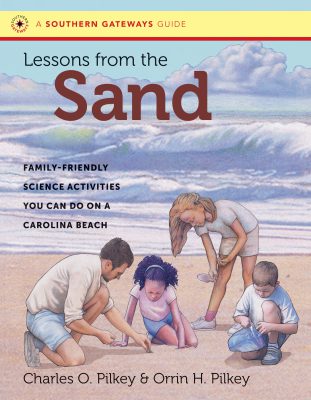

Five decades later, father and son have teamed up to write an activity book that intends to inspire the same love for beaches in children, and even in adults, through illustrations, questions and activities.

Charles’ artistic vision and writing ability, coupled with Orrin’s more than 50-year career as a researcher produced “Lessons from the Sand: Family-Friendly Science Activities you can do on a Carolina Beach,” which was published by University of North Carolina Press in April.

According to UNC Press, early sales have been strong with about 2,000 orders. Both Charles and Orrin are impressed by the response.

“We’ve got so many comments, all positive,” Orrin said. “Everybody sees that it’s a really different book. One bookstore said ‘we can hardly keep them on the shelves.’ Of course, every author wants to hear that.”

Supporter Spotlight

Charles said the philosophy behind the book was to showcase the spiritual, magical places he believes beaches to be and to teach the public how science works.

“We had to introduce the scientific method,” he said. “We had to teach them how to think.”

Both father and son share the belief that beaches are not just places to visit, but places to experience. They believe that science goes beyond a textbook, that it is best touched, seen and enjoyed in person.

The book is full of activities, from estimating wave height to identifying astronomical formations on a starry beach night, as well as bird and shell identifications. Charles also sprinkled the book with quotes from poems, literature and stories to merge science with the humanities. The book prompts readers to think for themselves through questions. For example, why are fossil sharks’ teeth black? Can you guess how shell layers were formed?

Orrin stresses the book is best enjoyed at the beach, where readers can get their hands dirty and shuffle around in the sand as they engage in the book’s activities.

“People are going to be looking at you saying, ‘What’s this strange kid doing?’” he said. “You should feel proud. You’re doing some science and all they’re doing is sitting there looking at the ocean. You’re learning about the ocean.”

Through science, Charles hopes people see beaches in a new light.

“If people recognize that beaches are beautiful, spiritual, magical places,” he said, “they’ll want to preserve them.”

A love for science, writing and education seems ingrained in the Pilkey family, where authoring books together is not uncommon.

Orrin wrote his first book, “How to Live With an Island,” with his father, Orrin H. Pilkey Sr., an engineer, more than 40 years ago. He has also coauthored books with his brother, Walter Pilkey, a mathematician, two of his other children, Linda and Keith, a geologist and administrative law judge, respectively, and a niece, Debbie Pilkey, who is an engineer.

This book, however, was a departure from Orrin’s usual academic and technical writing pieces, of which he has more than 250 published. The suggestion came from UNC Press, when Charles submitted another manuscript. He enlisted his father’s help for the activity book in 2013.

However, Charles said that during the writing process, his mother was diagnosed with kidney cancer, prompting Orrin had to take a step back from writing the book.

“At this point, he was taking care of my mom and I was doing the writing,” Charles said.

Over two years, Charles wrote almost all of the book’s content, designed each page and created illustrations. He would send his father the activities, who would check them for scientific accuracy. The pair even took trips down to the beach to try them out for themselves.

“We tested them in the field, he and I together,” Charles said.

For Orrin, this is where the joy of working with his children, who have long since left the nest, comes into play.

“They run away despite all the wonderful things you did, they go away,” he said. “But, here, when you’re working with them and discussing things over the phone or face-to-face, that’s what’s nicest, is the contact, the close contact with them.”

For Charles, working with his father builds on a bond he has shared with him his whole life.

“More than anybody, he has imprinted on me a scientific thinking,” Charles said of his father, “a skepticism that a scientist must always carry with him or with her and a rational, analytical view of the world. He’s been my mentor since day one.”

Charles said he doesn’t know why his family keeps writing books together, but he holds out hope that his 12-year-old son will also catch the writing bug.

“Hopefully,” he said, “my son will carry on the tradition.”