Last of three parts

NAVASSA – What will happen once the creosote contamination is cleaned up at the former wood-treatment site here? The town will have a say in answering that question.

Supporter Spotlight

The future uses of the site also depend on the results of an ongoing “massive investigation” of the contamination, explained Erik Spalvins, the Environmental Protection Agency’s remedial project manager for the Navassa site. Everyone’s goal, he said, is to begin some kind of redevelopment as quickly as reasonably possible.

“We don’t want to leave a cleaned-up site with a fence around it. We want to leave something more,” Spalvins said.

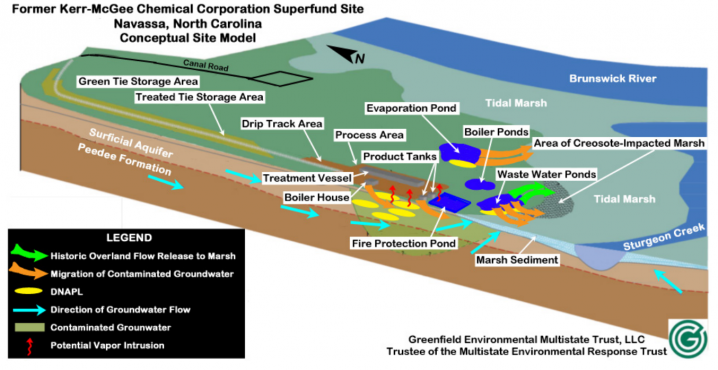

The wetlands at the site, about 92 acres, became property of state in the 1990s. Most of the property – Kerr-McGee owned about 251 acres total – now belongs to an entity known as the Multistate Environmental Response Trust. The trust was created in 2011 as part of a bankruptcy settlement involving more than 400 polluted Kerr-McGee sites in 24 states. Money given to the trust from the settlement can only be used to clean up those sites.

Spalvins said the upland areas, parts of the site never used for wood treatment, will eventually be removed from the Superfund designation. Uses of these areas may not be restricted at all. Other parts of the site, while they may never be appropriate for single-family homes – “That may not be an efficient use of funds,” Spalvins said – could see some kind of residential use.

“Based on what the community is interested in seeing, some type of residential use could be possible as long as we don’t have that direct exposure,” Spalvins said.

Supporter Spotlight

It is likely businesses could operate there, possibly public facilities.

“We’re really trying to focus on what the community’s vision is to guide that future land use and how we accommodate that future land use with the engineering and construction we have to do,” Spalvins said.

The site is an unusual property, he noted, in that it’s a time capsule where nothing has happened since the late 1970s. Otherwise, the property would have likely been developed.

EPA officials, when they meet again with the community later this year, hope to build a relationship that allows an exchange of ideas. Spalvin said he expects frequent meetings with local government officials or a community group, in addition to meetings with contractors, state officials and representatives from the trust, but there’s no definite timeframe for redevelopment.

“We’re trying to have a regular presence in the community as we do this cleanup to give them a voice in what happens in their backyard,” Spalvins said. “I hope in the next year the community can articulate a vision of what they’d like to see.”

The Investigation

Multistate Trust contractors have, during the past 18 months or so, taken about 500 samples at the Kerr-McGee site. Some of the unknowns at the site include how deep or widespread contamination is in the soil and groundwater and whether contaminants are migrating from drainage swales on the site into tidal marshes. It’s also been unclear whether people can be exposed to contamination and whether that exposure poses an unacceptable risk. Also, it hasn’t been established whether vapors from groundwater contamination might migrate through soils into future buildings at the site.

“We had a pretty massive investigation in the swamp where we put some mats out and we were able to drive out over the swamp and take samples so we could understand what was happening under the swamp and pin down exactly where contamination is, how bad it is and how far it went,” Spalvins said.

The results will determine which parts of the site need action and where it might do more harm than good if action is taken.

“We don’t want to take an action in the swamp if it’s going to harm the swamp and if the contamination isn’t causing any problems with the ecosystem,” Spalvins said.

Later, possibly this winter, contractors will start to look closer at areas they have not been able to access previously. By next spring, the team will begin to summarize where contamination exists and what can be done.

The work takes time, Spalvins said. “Every time we collect samples we find more questions,” he said.

The goal is to meet at least twice yearly. Officials with the state Department of Environmental Quality are also involved.

What Are the Risks?

Worker safety, the health of nearby residents and the danger of further damage to the environment are major considerations with a project like this, Spalvins said.

“The whole point of the cleanup is to protect human health and the environment,” he said.

In terms of the environment, decisions must be made as to whether to excavate or immobilize the contamination. There are tradeoffs in both.

“Do we destroy the swamp to save it?” Spalvins said. “At what level is contamination causing issues with wildlife or unacceptable exposure up the food chain, or people? Where do we draw the line?”

The marsh itself offers some advantages, mainly because of the large amount of organic materials that absorb contamination like a carbon filter.

“One of main features of the groundwater at this site is the tidal nature of this ecosystem. It complicates it but it also lets mother nature do a better job of dealing with the contamination on her own,” Spalvins said. “Twice daily, the change in tide means groundwater is not moving in the same direction or at the same speed all day. That’s done a lot to help reduce the overall impacts.”

Restoring the Ecology

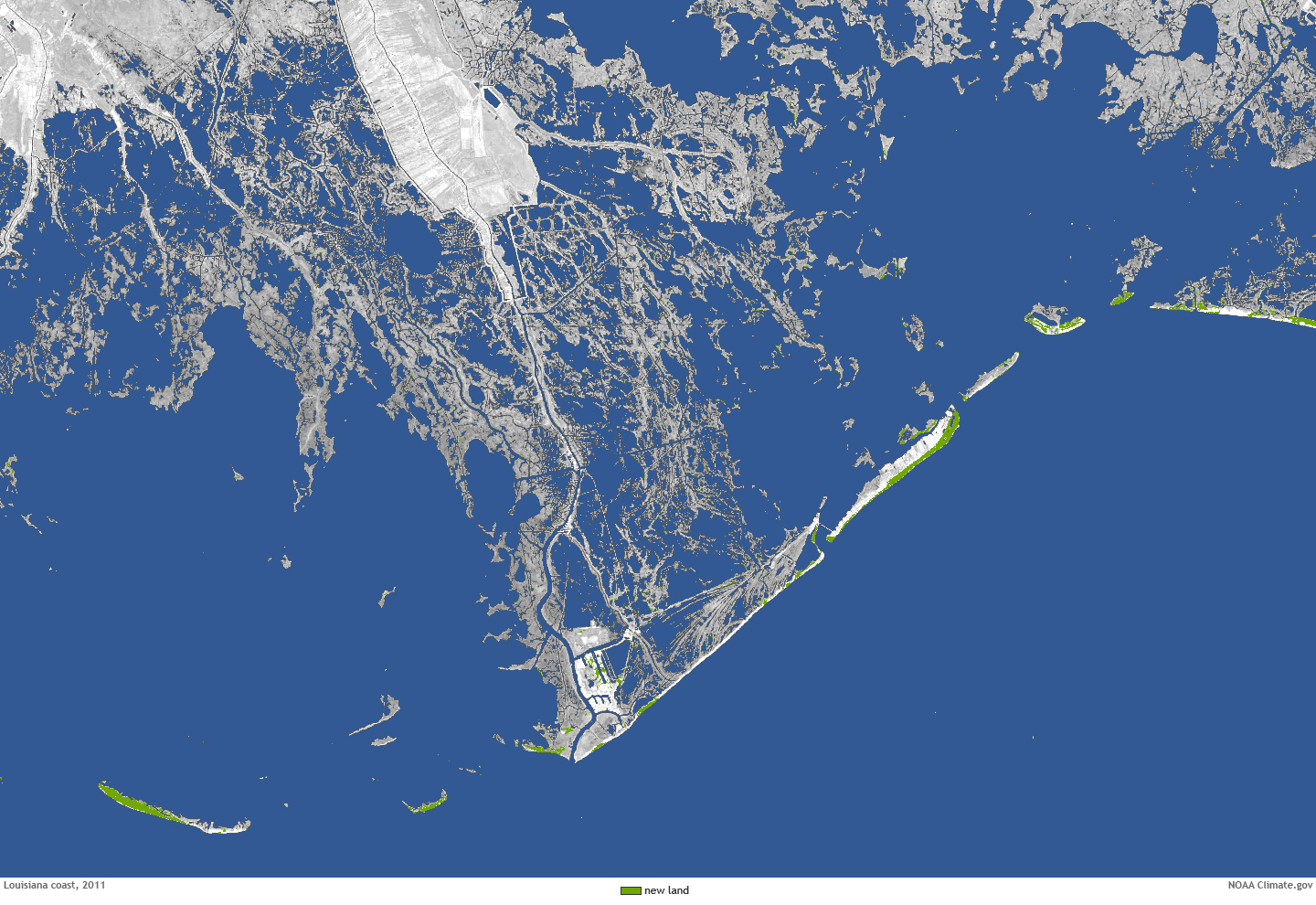

Because the contamination damaged natural resources, including fish, wildlife, water and wetlands, the Navassa Trustee Council was formed as part of the 2014 court settlement that spawned the cleanup. The council includes representatives from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NCDEQ to oversee restoration or offsetting of natural resources that were damaged.

In addition to the money and effort focused on cleaning up contamination at the site, about $23 million from the settlement is dedicated to restoring and correcting natural resources lost to contamination. NOAA is the lead trustee dealing with the natural resource damage assessment.

Habitat restoration will take place away from the Kerr-McGee site, said Howard Schnabolk of the NOAA Restoration Center in Charleston, South Carolina. NOAA is seeking help from the public in how to best spend that $23 million.

“We are charged with addressing the ecological injury,” Schnabolk said Tuesday. “The community has a lot of other issues, human health issues, damage to their property. We’ve made an effort to explain where our trustee group can help and where we can’t. The EPA effort has a lot more focus on social support – jobs, economic development, social issues.”

NOAA reached out to the public about a year ago for ideas on how to proceed.

“We put word out to the public explaining what we’re doing and that we’re looking for habitat-restoration projects to compensate for that ecological loss,” Schnabolk said.

The public responded with various ideas, he said. NOAA is now in the process of evaluating proposals.

“We intend to start spending some of the funds on projects soon, but before we spend, we need to put a restoration plan together and get it out for a 30-day review,” Schnabolk said, adding that the goal is to release the plan to the public early in 2017. “We’re still willing to entertain project ideas from the public. We haven’t officially allotted one dollar yet.”

The North Carolina Coastal Federation has applied for about $1.8 million in grants to do restoration of marsh and estuarine habitats in the lower Cape Fear River, an affected area about 15 miles downriver from the Kerr-McGee site. The federation’s proposal includes building fish and oyster reefs at Carolina Beach State Park.

Some in Navassa have expressed frustration about how the money may be spent. Schnabolk acknowledged the process may be difficult for the community to understand.

“We struggled a little bit to explain,” he said.

Environmental justice advocate Veronica Carter said many in town were upset when the trust settlement representatives held a meeting last fall to discuss restoration.

“They were like, ‘Wait a minute, what about us? Our people have been dying off for years,’” Carter said. “You’re more concerned about the critters than the people.”

Carter said it’s imperative to clean up the entire river basin, not just the Kerr-McGee site. “They drilled 78 feet down (in Sturgeon Creek) and found creosote,” she said.

Schnabolk said the mayor has helped bridge the communication gap with townsfolk.

Power Struggle

Navassa has been without a town administrator for several years. The town council had assigned certain administrative duties to Mayor Eulis Willis, but in January, the board voted 3-2 to strip the mayor of those duties. Willis said the decision related to “town business in general” and had nothing to do with his involvement with the Kerr-McGee cleanup. But that could change.

“The major impact that could happen is if, administratively, they decide ‘Well, mayor, we don’t want you to have nothing to do with none of this.’ And they could put some checks in place,” Willis said.

Councilman Athelston Bethel began a four-year term on the town board in 2015. Bethel said he’d like to see the council more involved in decisions related to the Kerr-McGee site.

“We’re asked to vote without having all the information,” Bethel said. “I’m his biggest opposition. I like the mayor, he’s good for the town, but we always felt the mayor ran the town and not the council.”

Bethel said he and other board members were briefed on the cleanup and restoration.

“We walked through the property and discussed what we would like to see done with the property and that’s as far as it went,” Bethel said.

Still, Bethel said he feels comfortable with what he knows, but he wants to be in on the discussions and not being invited to meetings about the site bothers him. This includes a locally appointed restoration group.

Louis “Bobby” Brown is a member of that group, which he said met Friday. Brown told CRO he couldn’t discuss what happened at the meeting because he’s bound by a confidentiality agreement.

Bethel said it’s possible the mayor doesn’t want the town council’s input.

“Perhaps it would destroy what he’s trying to do,” Bethel said. “He goes to Atlanta to EPA meetings. He comes back and doesn’t say anything to the council. He talks to the committee. His thing is that the committee is responsible.”

Willis defended his role in the process. “I’m the one who understands what’s going on,” he said.

Schnabolk agreed, adding that he stays in close contact with the mayor.

“We’ve worked through the mayor to understand what the community’s needs are,” Schnabolk said. “The mayor’s done a good job at working with local landowners to identify projects and put us in contact with them. He’s like a broker. He’s the go-to person for me.”

Willis has long been the most familiar face of Navassa, appearing as town spokesman on numerous issues during his tenure. He’s also led several fights when it appeared the town had been slighted. His advocacy on behalf of the town, where his family goes back at least nine generations, includes fighting for highway and bridge funding, economic-development attention and revitalization grants. The highway into town bears Willis’ name. Willis said he’s a direct descendant of the first black man to purchase land in Navassa back in 1875.

Bethel said other voices in town deserve to be heard. Increased media coverage of town business could help open the discussion, he said.

“I’d like to see more press at meetings. It’s vitally important at this juncture when we’re fighting for what is right for this town,” Bethel said. “Navassa is sort of a close-knit town and people don’t like the fact that the mayor has all the say with the media. They feel like they don’t get a true picture.”

Bethel praised the mayor and his fellow council members for working for change, but he said much is needed in town, especially a library and a cultural center. The town, along with the North Carolina Land Trust, received earlier this year a $25,000 grant from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation to create plans for a heritage center focused on the community’s Gullah-Geechee culture and to protect land in the vicinity with Gullah-Geechee significance. Much more is needed, Bethel said.

“We don’t have anything in Navassa,” Bethel said. “We don’t have a service station. There’s not a coffee shop for the guys to hang out in the morning.”

Looking Ahead

Mike Hargett, Brunswick County’s director of economic development and planning, says town officials appear to be on the right track.

“It’s a forward-thinking community and they embrace progressive ideas,” Hargett said. “We’ve seen brownfields developed into usable sites. I think they’re to be commended for those efforts.”

Hargett said the Kerr-McGee site would be attractive for commercial or residential because of its waterfront.

“The water frontage on the river gives quick access to the port and Navassa will soon have very convenient access to I-140 with an interchange that will provide access to the interstate. Water and sewer are available and rail. Those are pretty key components to serving an industrial site,” Hargett said.

The only way to make the Kerr-McGee site marketable is to clean up the contamination, Hargett said. “Lenders are not willing to finance a project where there are environmental issues,” he said. A clean site, however, could work for a mixture of industrial and residential uses.

“Mixed use is a great idea,” Hargett said. “The waterfront location is ideal for residential and with advanced manufacturing that we have these days, they certainly could co-exist with an intelligent site design. There are some sites like that in the county. Navassa has approved a site that includes a mixture of commercial and residential called River Bend. It’s undeveloped as yet but I thought it was a very intelligent design for that site.”

Willis has pursued economic development projects on his own. He led efforts to lure a boat manufacturer to town. He also fought to attract an auto and appliance recycling company that wanted to build a landfill in Brunswick County. The boat manufacturer, closed in 2008. The recycling company, Hugo Neu, never broke ground. The project met widespread resistance because of its potential environmental effects. Critics said the company eyed Navassa because of its low-income, predominantly black population, but the company said the site was recommended by state and county officials. Willis is still upset the project didn’t happen.

To Learn More

- Multistate Environmental Response Trust

- NOAA’s Damage Assessment, Remediation and Restoration Program

- Brunswick County Economic Development

Read Part I: “A century of contamination”

Read Part II: “From guano to creosote”