KITTY HAWK — Like the seashells that are strewn along its beaches, the North Carolina coast is scattered with stories about its cultural history. Native Americans, European explorers, pirates, shipwrecks, lifesaving, lighthouses, fishermen and boat builders are all examples tucked away in its salty and sandy archive. As time has passed, remnants of our cultural landscape are becoming less familiar unless you take the time to seek them out.

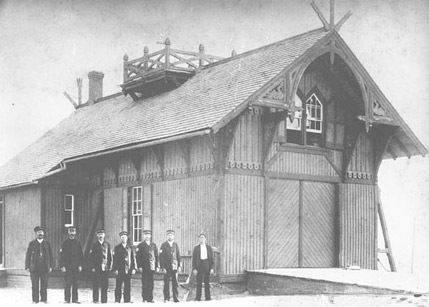

One such gem, the Kitty Hawk Lifesaving Station, is unrecognizable, disguised as the Black Pelican restaurant along the Outer Banks. Even though the old station has already been moved twice to escape the ocean tides, large piles of brown sugar sand dunes are still needed to protect it from the surging waves. After many additions, the gingerbread trim near the peak of the gable roof is the only hint of its past life.

Supporter Spotlight

You know that old saying about talking walls telling tales? These old walls could spin yarns of triumph and achievement, anger and violence, hope and rescue. They could even whisper tales of ghosts and the supernatural.

In the mid 1800s, with the increase of maritime traffic along the East Coast, it became apparent that land-based rescue stations were needed to assist stranded and wrecked ships. When hurricanes and nor’easters pounded the coast, ships along the barrier islands frequently grounded on uncharted, invisible and deceptive sand bars. The early lifesaving stations relied on volunteers with rescue boats and equipment provided by the federal government. But a strong hurricane in 1854 revealed that these makeshift stations were overwhelmed by the task of rescuing sailors in rough seas.

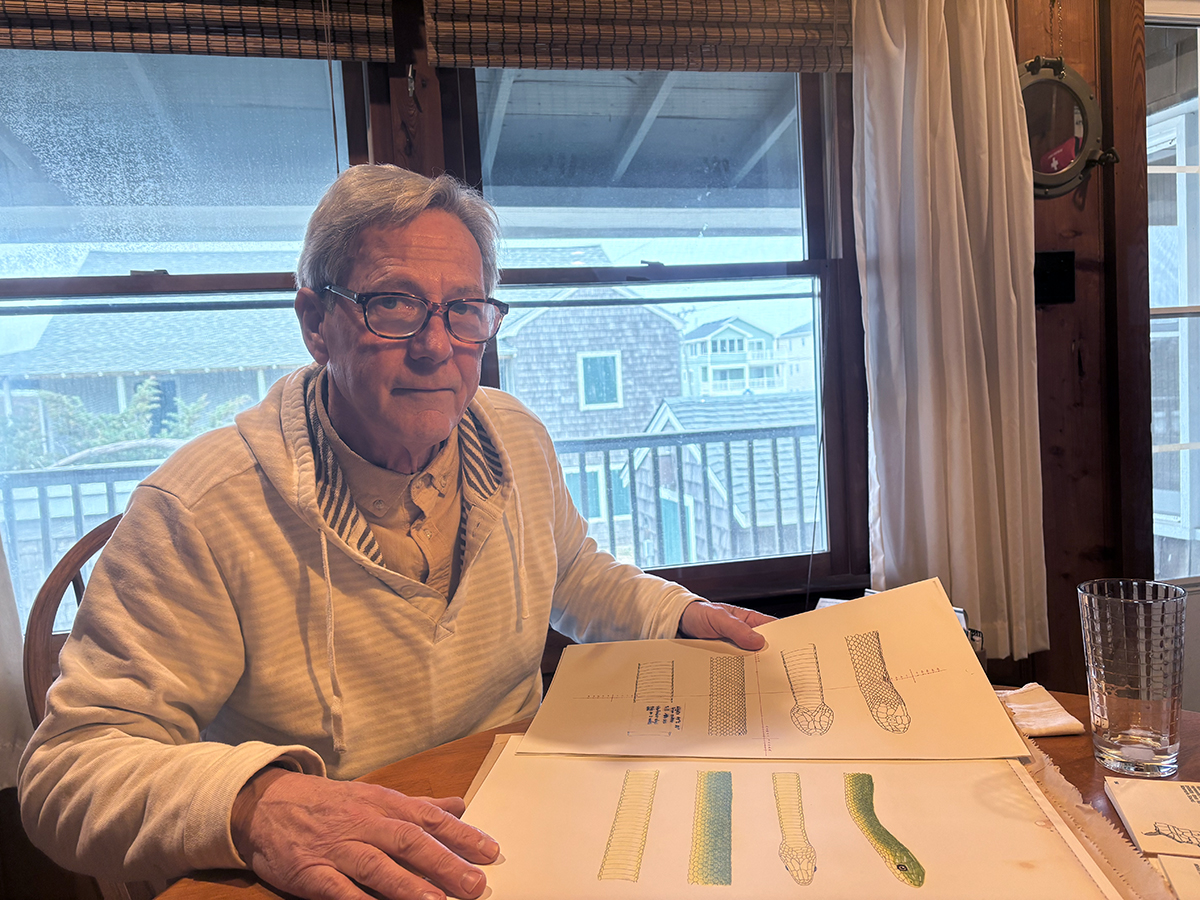

By 1874, a number of lifesaving stations were constructed along the islands, including one in Kitty Hawk. The stations typically consisted of a crew of seven men, a keeper — usually referred to as captain — and six men with experience as mariners, sailors and fishermen. W.D. Tate was the station’s first keeper and was replaced a few years later by a man named James R. Hobbs. Like all keepers, Hobbs worked his crew six days a week keeping them sharp and prepared. They drilled often, launching their boat from the beach through the crashing breakers in all kinds of weather. They patrolled the beach up to five miles on foot, stood for hours in the lookout tower — chairs were forbidden — and practiced signaling and first aid.

The Kitty Hawk station was on a long stretch of open, sandy shoreline. The isolation here was no different than that of a becalmed sailing ship at sea. The crew worked together, lived together and in the confines of isolation may have gotten on each other’s nerves.

Theopolis L. Daniels, by some accounts was one of Hobbs’ men. Other accounts imply that he was a local after Hobbs’ job. Either way, Daniels leveled serious charges against Hobbs, accusing him of using his government position for personal benefit. This included using government-owned paint to paint his private boat, using the men under his charge to carry out chores on his personal farm and the serious accusation of absconding with goods from a shipwreck.

Supporter Spotlight

According to a Hobbs’ telegraph, Daniels detested him and always greeted him with unfiltered profanities, vulgarities and insults. It is reported that things went too far when Daniels insulted Hobbs’ wife and may have spit tobacco juice on her.

Daniels repeatedly reported the charges to Hobbs’ supervisor, and an investigator was sent to sort out the accusations and resolve the matter. Inside the station, the investigator began questioning Daniels, but once Hobbs stepped into the room, Daniels began threatening Hobbs and reached for the pistol in his pocket. As Daniels worked the gun out, Hobbs pulled a shotgun from a closet and fired twice, fatally wounding Daniels. Hobbs’ report about the incident stated, about Daniels, “He died with his revolver cocked in his hand.”

Daniels’ body was said to have been buried at sea and the investigator declared it a case of self-defense.

But Daniels, it is said, is still restless. His spirit is said to bang about inside the old station house, now the Black Pelican restaurant, where he was killed. Workers at the restaurant report mysterious noises and shadowy figures lurking around. So prominent are these reports that the restaurant is listed as one of the spooky haunts of the Outer Banks.

Sixteen years after the killing of Daniels, in 1900, the Kitty Hawk station, which also served as a weather bureau and a telegraph office, was visited by two strangers from Ohio with big dreams of flying. The Wright Brothers, Wilbur and Orville, arrived to conduct glider tests at nearby Kill Devil Hills to see if the area was suitable for their experimental flying machine. At the station, they sent messages back home and received vital weather information.

Just down the beach from the Kitty Hawk station was the Kill Devil Hills lifesaving station. When off duty, the crew of the Kill Devil Hills station was frequently volunteering to assist the two brothers in their attempt to fly their homemade motorized flying contraption. Viewed as polite, lovable nuts, the Wright Brothers were welcomed by the men of the stations. Orville and Wilbur owe a debt to the men of the station as they were indispensable in running errands and were, essentially, the first ever airplane ground crew.

On Dec. 17, 1903, with a 30 mph northeast wind stinging their faces, the Kill Devil Hills crew never hesitated to help on that icy, cold morning when their plane glided above the dunes. The iconic first flight photo was actually snapped by one of the surfmen. With four successful flights, the brothers, after eating lunch, calmly hiked over to the Kitty Hawk lifesaving station. Here, as the heels of their shoes scuffed across the wooden floor, they handed the telegraph operator a note. The tapping of the telegraph machine was vibrating through the walls of the station sending the news of their triumph, manned flight had been achieved.

After the successful flights, the brothers continued to return to Kitty Hawk for a number of years refining their aircraft among the open dunes. They still relied on the generosity of the lifesaving stations and the crewmen. In 1908, they even nursed Wilbur back to health in the Kitty Hawk station when he came down with a bad case of the flu. Because of their relationship with the Wright brothers, many of the surfmen went on to become local celebrities.

Serving at one of these remote, lonely outposts was most likely, at times, quite boring. From the vantage point of the lookout tower, the men scanned the horizon for any sign of a ship in distress. Often, the gaze of the lookout spied the familiar shape of a lone pelican gliding above the mist of the ocean spray. This pelican was different however, it was not the colors of a typical brown pelican, it was completely black, the color of coal. It soon became apparent that the appearance of this bird was followed by incidents of bad weather or ships in need.

When the winds whipped the sea into frothy foam and storm clouds obscured the vision of the lookout, the black pelican appeared. This was a signal for the “storm warriors” to prepare their equipment. It is said that the bird often guided the boat crew through the waves locating wrecked boats and survivors to be rescued. If you think this is just a myth, Station Keeper Tate also mentioned the black pelican, which he referred to as a “watchdog” in his journal. Survivors of shipwrecks also noted in their diaries that the pelican glided just above the surface of the water and soared above giving them the hope of rescue in a dreadful situation.

Throughout the history of the station, crewmen reported the resolution of the black pelican to assist in rescues or to warn of dreadful weather. In 1915, the Life-Saving Service merged into what is now the U. S. Coast Guard. Eventually, many of the lifesaving stations were shuttered and abandoned and sightings of the black pelican became less and less frequent. Today, boaters along the Outer Banks continue to report a black pelican when weather is at its worst. Perhaps this soot-colored savior bird was merely a wayward magnificent frigatebird soaring the ocean skies. Maybe it was just a brown pelican with a rare melanistic color variation causing it to be all black. Either way, it doesn’t matter, for those in need it was a guardian angel, masquerading as a pelican.

While many fascinating stories of our cultural history are fading away, at least one legend of this sturdy old building lives on through the name of a restaurant.