Last of two parts

An expert in the acoustics of the ocean and an environmental advocate question whether seismic surveys off the N.C. coast for oil and natural gas can be done without harming marine life or interfering with commercial and recreational fishing.

Supporter Spotlight

Michael Stocker is the executive director of Ocean Conservation Research, a nonprofit research and policy development organization in San Francisco. He is a bio-acoustician with a dual background in physics and biology who has studied the interaction of sound with marine animals in the ocean since 1992.

Ladd Bayliss, the coastal advocate for the N.C. Coastal Federation in Manteo, addresses additional impacts that a seismic operation could have to fisheries activities and marine life.

Michael Stocker

Q. What is the extent of the issue of noise pollution in the ocean?

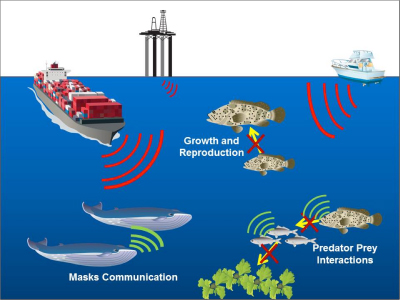

It’s a real significant and growing problem, and there are a lot of sources. In the last 50 years, from international trade and shipping, the ocean is 10 times louder than it was. That’s all pretty much low frequency. It’s louder because of shipping, and it does have biologic impacts. The problem is, no baseline was taken back in 1965. As it turns out, back in 1820, with whaling, the ocean was pretty loud as well. In 1965, it was probably as quiet as it had ever been.

But biologic noise is different. There’s acoustical niches that animals use to communicate in. In any healthy biophony, you’ll hear some animals using low-frequency sounds, some using high-frequency sounds, some mid-frequency sounds. They rarely interfere with each other. They have these acoustical channels. (Low-frequency sounds broadcast farther.) All this biophony sounds like a well-tuned orchestra when it’s working right.

Supporter Spotlight

What we’re doing with the shipping noise – that’s just broadband hash. It’s like being next to a freeway. It’s limiting the broadcast ability for animals at long distances. The consequences for the great whales – they communicate at low frequencies – is they’re trying to communicate through this acoustic smog.

After 9-11, according to a study of whales, for about a week, they shut down all shipping – the cortisol levels that indicate stress went down immediately. It was really quite clearly correlated. As soon the noise levels went up again, the stress levels in the whales went up.

Q. Can you explain the impacts of seismic and sonar technology on marine animals?

The whole ocean is an acoustic environment. Light doesn’t really work so well under the water. So most animals are adapted to complex hearing systems. And some just hear, and others make noises.

The first sonar was developed after the Titanic. Of course, it was used in the war, by submarines. Humans have been basically bouncing sounds around in the ocean for less than 100 years. Whales have been bouncing sound around for 30 million years. So they have a refined, complex system. They can see things quite clearly.

Some sonar is not necessarily harmful – just an annoyance. The mid-frequency sonar associated with these mass strandings is a pretty nasty sound. What’s really a problem is offshore fossil fuel development. The surveys are these low-frequency pulses. Argueably, because of the low-impulse speed, that they’re not physiologically damaging to these animals. You can say, well it’s not killing anything, you’re not seeing animals floating on the surface. But when they hear this rumbling all the time, it’s like the shipping noise – it’s going to raise anxiety. It happens in the whales; it likely happens with fish. When the animal is in a constant state of stress, it interferes with their biological function, with their breeding, their community. If they don’t like it, they have to depart. Or with fish, they’ll typically shelter in place. It’s not healthy.

Q. With regard to takings, what would be the impact of 2-D surveys on marine mammals, sea turtles and fish?

Well the sea turtle stuff is still ambiguous. We do know when ships are in the area, they try to leave. We see disruptions in migration of fish. One of the things we need to look into is that fish don’t seem to respond to amplitude. We humans are sound-pressure sensing animals. Some fish have that ability – they have an air bladder that responds to pressure gradients. But most fish tend to have cilia or accelerometers in their hearing system, which allows them to sense particle motion. When a sound happens, it flexes the medium back and forth, almost to a molecular level. That is one way they sense sound – proximity is more important than amplitude in many fish.

Marine mammals hear more the way we do. They have inner ear, cochlea, frequency discrimination. And because of their adaptations, they have very complex relationships to sound environments. So while we know that dolphins use bio-sonar to sense their surroundings and communicate with each other, we’re beginning to see evidence that larger whales use these low frequencies to navigate. They may bounce these sounds off of females 300 kilometers away, and they know where they are.

Q. So this would clutter their ability to navigate?

Yes. Also, (some species of whale) are built for speed. They’re high-speed animals and unlike the humpback whale which uses a very beautiful song they sing, these animals pulse kind of like crickets, every 10 or 15 seconds. Well this is the same pulse width of a seismic survey. There’s interesting evidence, from a study monitoring fin whale migration in the Mediterranean, that found they went partway to their breeding area and turned around. Researchers found there was a seismic survey going on in the area. Those pulses, even though they were quieter than the noise levels of the ships, somehow spooked these animals.

Q. Do you know if there is a long-term biological impact from surveys being done for a short time? For instance, do the animals leave for good?

We’re beginning to see from studies done on bowhead whales in the Arctic that there are migratory disruptions. They’re changing their vocalizations. The North Atlantic right whale is having a really hard time. The South Atlantic right whale, on the other hand, they’re really successful. What’s the difference? The northern hemisphere is really industrialized – shipping news, entanglements, there’s a lot of human interference. The southern hemisphere – not so much.

Q. Do you have an opinion on how effective the mitigation tactics are that BOEM or NOAA requires? Are they effective or enforceable?

Frankly, a lot of them are like, what the heck, let’s try this out. The 1,000-meter setback, for example, yeah that’s fine and dandy, except, as one study showed, these animals were responding to signals 150 kilometers away. It freaked them out – they did not migrate. The same with the bowhead study. These animals were 10-15 kilometers away, and the sounds were disrupting them. With ramp ups – the idea is if they don’t like the sound, they’ll leave. Yeah, what if they’re feeding, what if they’re comfortable with the area? What would happen if somebody moved into your neighborhood and decided they were going to be playing low-frequency boom, boom, boom all day long? We have the choice – we call the cops.

Q. So the problem with seismic is more of a harassment, rather than an injurious thing?

The physiology is, in the longer term, if you’ve got a lot of anxiety it will compromise your immune system.

Q. What about the impacts of overlapping projects?

This is one of those things that was not accounted for. Right now, there are four Incidental Harassment Authorizations under review at NOAA Fisheries. And we’ve paused those guys. Once reason is they’re gargantuan. The other is they’re concurrent. For example, let’s take this idea that this ramp-up procedure will let animals leave the environment where they’re subjected to this. But they have another one 40 kilometers up the coast. They have no mechanism in the review to look at concurrent assaults. They take each one at face value. What are you doing to these animals? You’re turning their whole environment into scrambled eggs. Let’s just say, there’s only one going on, but there’s this shipping lane. The level B guidelines are outdated.

Q. Well what are level B guidelines?

Level A impacts are physiological impacts. Level B are behaviorials. It’s disrupting feeding behavior, having them move their migration paths, those things that have them disrupt their natural behaviors. There’s so much evidence that behavioral impacts happen at significantly lower levels than mitigation thresholds are set.

Q. This issue of takings, it makes it sound like they’re being killed or injured. No instances of takings by contractors.

We can look through whatever end of the telescope you want to look through. Low-impact pulses are not going to hurt an animal physically. But the level B takes, when you have an animal whose natural behavior is disrupted, what are the biological consequences of that? That’s what the discussion should be. These animals are evolved to live in an environment when they will be subjected to stresses, they need to be on the alert. But they’re being subjected to noises that they haven’t been habituated to.

Q. How can we lessen the impact of noise in the ocean?

We have to look at the scale of it. There’s technology to attenuate noises like pile driving. They’re coming up with air guns that are lower frequency. That’s an improvement. They want to have really accurate 3-D maps on what’s happening below the seafloor. In order to be really accurate, they need to bang and bang and bang and bang. They want to sell the data because it’s valuable – that’s why there are four companies wanting to do the same thing. At what cost? These guys are over-equipped right now.

We need to scale down. We’ve got to keep (oil and gas) in the ground if we’re going to survive on this planet.

Q. So you’re talking about a change in public policy and the regulatory process?

Yes. It’s all about making money.

Ladd Bayliss

Q. What are your concerns for fisheries and marine mammals with seismic surveys in the Atlantic?

Eight companies have active permits in the Atlantic right now. The main concern in all of this is that all these companies have overlapping survey areas. Which means that, because they’re overlapping, they’re going to potentially occur in the same place, and possibly at the same time. So, I think there are two main issues. One is the access issue – what kind of problems will we see with other industries that are already operating in the ocean and will continue to need to operate in the ocean during these surveys. And then what kind of impacts will there be to marine life? A piece of it that is less studied than impacts on marine mammals is impacts on fisheries. Other living things in the ocean can be adversely impacted by one survey, and especially by the eight that may happen.

Q. What is the status of the applications?

The eight companies have submitted applications to BOEM to conduct geophysical surveys of the Atlantic. They go through this long winnowing process that basically routes them through every important agency in the federal and state governments to figure out what these impacts of these surveys could be. So five of these companies are farthest along in the process.

The NMFS is dealing with the main issue of this, which is marine mammals. This is the last permit they would need – approval or denial to authorize these companies to interact with marine mammals. Once these decisions come from NMFS it will go back to BOEM, which will issue final permits.

Q. Is there a process for coordination between survey vessels and recreational boaters and commercial fishermen?

I wouldn’t say there is a really structured process. The one process I would say a lot of states have used to coordinate these type of uses is the consistency determination. One piece of BOEM’s seismic permitting process is consistency determination. So basically every state on the East Coast should have a coastal management plan that allows states to weigh in on any federal activity that occurs off their coast. Each company had to go through and apply separately for a consistency determination. All of the states said, yes, it is consistent. The majority of the states said yes, but you have to abide by these conditions. A lot of these conditions included specific time and area closures, avoidance of essential fish habitat, avoidance of special geographic ocean features like canyons.

All of these things, obviously, are really important to commercial and recreational fishermen.

One thing we noticed that was glaring about North Carolina was there were no specific details in the consistency determination for these companies. And we think that is a big missed opportunity. We’ve been lucky enough to work with Spectrum Geo individually, and they have been incredibly accommodating, specifically with commercial fishing access issues. As far as how is our state commercial fishing industry is going to interact with surveys that they may or may not conduct. I think the state could’ve done a much better job specifically detailing when or when not these surveys could take place. And since they did not to the degree that other states did, the onus is now on the individual users to contact individual companies like Spectrum Geo.

Dewey Hemilright, who is a member of the Mid-Atlantic Fisheries Management Council, as well as commercial fishermen, has completed a map specific to the pelagic longline industry that shows when and where pelagic long-lining happens off the coast of North Carolina. Dare County has helped him construct that map and that map is being sent to Richie Miller. It’s a very simplified process, but we literally had a conversation with Richie and talked about, if these happened, how are we going to work together to mitigate for the existing industries that are already out there?

Q. Are there other issues fishermen have been concerned about that haven’t been addressed, or will be addressed?

I think there are two issues. First is the logistical issue. Each company typically tows survey gear that’s about 6½ miles long. And this is behind an already 200- to 300-foot-long ship. These survey boats obviously have exclusions, so you can not be in this usually 10-mile area because of all this expensive gear and the possibility for interaction.

And the other logistical hurdle is a little more specific – it’s just the amount of water that they’re going to be covering, from about three miles to 400 miles offshore. And that survey is barring any big weather incident, will take place 24 hours a day, seven days a week. In the permit, they do include down days for weather, but some of these surveys can run up to a year.

The other concern, obviously, is what happens to the marine life that is already out there. The impact to fisheries is a lot less studied. There is one study about cephalopods about how low-frequency sound has produced significant trauma in giant squid off Spain. It’s hard to correlate strandings of these animals with seismic, or low-frequency sound. But this study shows that the sound perception in invertebrates is not very well known, even though they play such a crucial role in the ocean ecosystem. This study proves that that there is a detrimental and serious effect, sometimes causing mortality, in cephalopods from low-frequency sound. Which is kind of an indicator species in the ocean – there are a lot of species in N.C. fisheries that depend on squid and other cephalopods to survive. I think that’s a really interesting piece in all of this – is looking at these at how these other things in the ocean are going to be affected.

There’s another study that talks about bottom-going rock fish on the West Coast, on how geophysical surveys have an effect on behavior. I think the thing that’s difficult about fish is that the sound from air guns is most likely to cause behavior changes in fish, not necessarily physiological changes. But this study found there was a 52 percent reduction in the catch-per-unit effort. And that reduction was due to a behavior response. I think that’s really significant. I know all species are going to be affected differently. But the point is we need to really think about this. We don’t know how these surveys are going to impact species other than marine mammals.

Q. How can seismic survey work be done in a responsible way?

I’m not sure, but I’m not sure we should have eight companies surveying the same bottom. I understand it’s proprietary data, and this is an economic gain for these companies to survey and sell the subsequent data. But it seems that other countries have figured out other ways to do just one survey and sell that. Obviously, if we can reduce the amount of times that we’re putting noise in the ocean, that would help. I’m sure a lot of geophysical companies think differently about that.