First of two parts

Though drilling for oil or natural gas off the East Coast coast is currently off the table, the federal government is still evaluating permits from several companies to use sonic air guns to survey the Atlantic seabed for oil and gas deposits.

Supporter Spotlight

The National Marine Fisheries Service, known as NOAA Fisheries, is currently reviewing applications from the companies to harm or harass whales and other animals protected by federal law. These permits, which would put limits on disturbances to marine mammals, is one of the final requirements before seismic projects are approved.

The testing off the N.C. coast could begin later this year.

Air gun noise is believed by marine scientists to have potentially detrimental effects on fish, sea turtles and marine mammals, including the endangered North Atlantic right whale that migrates off the southeast U.S. East Coast.

Proponents, on the other hand, say that there is no evidence that directly link the tests to harmed whales, fish or turtles. Such tests, they say, are needed to allow oil companies to better judge the locations and quantities of oil or gas deposits.

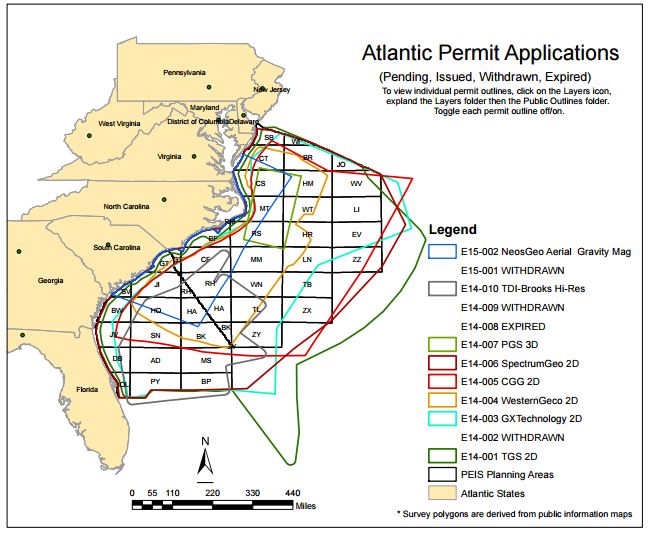

Over the next two days, Coastal Review Online will present interviews to people on both sides of the issue. We start today with Richie Miller, executive vice president at Spectrum-Geo’s office in Houston, Texas. The Norwegian-based seismic survey company is one of five applicants seeking permission from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management to do seismic surveys off the southeast Atlantic coast to look for oil and gas deposits under the ocean floor.

Supporter Spotlight

Miller, 53, has more than two decades of experience in the seismic industry

The transcribed telephone interview that follows has been edited for clarity and space only. Miller didn’t receive the questions in advance.

Q. The last time the Atlantic was surveyed for oil and gas prospects was in the ’70s, is that correct? Was the equipment used then the same type of technology?

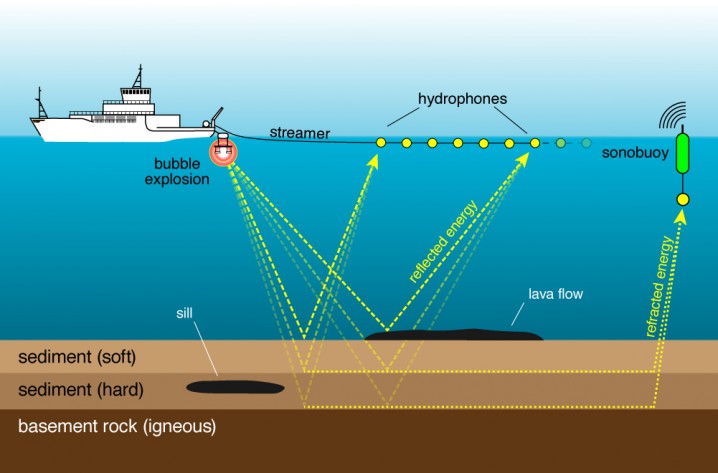

Yes, in the ’70s-’80s. Yeah, it’s the same physics, a lot of the same equipment. Really, the big difference is it’s just a longer cable.

Q. As a prospective contractor, can you explain why, in the absence of a planned lease sale, it is useful to do surveying now in the Atlantic, rather than waiting until there is a planned sale?

There’s a new play – it’s four or five years old, what we call the Atlantic margin. So what science has found is that the hydrocarbons that are discovered in say, offshore Brazil, you have this the same type of geology, the same age rocks, the same type of oil in Angola. It’s the transatlantic margin, is what we call it.

The Atlantic margin play is what we call its congregate, it’s what lines up (with ancient continents) Pangaea, Gondwanaland. When everything split apart, the congregate of the East Coast of the U.S. is really from Georgia northward is Guinea-Bissau, where Morocco hits more up toward Maine and Canada. Then you actually have Spain and Ireland and all that kind of mashes up farther into Canada and Greenland.

The reason I would be out to acquire data is to get a regional framework of the U.S. Atlantic – that is a marketable product to help understand the exploration that’s going on in West Africa. That’s the bottom line.

Q. What parts of the puzzle would match up with the N.C. coastline?

It’s probably right around Guinea-Bissau or Gambia and Senegal. It’s the northwest coast of Africa.

Q. So there’s been new discoveries of hydrocarbons there?

There are other theories that where there’s hydrocarbons on one side, there’s not hydrocarbons on the other. So people are playing that on down in South America. It’s a relatively new play. People are looking at new science to try to help understand it.

That’s one reason. There’s still is a want to understand with new data – what’s the resource base of the East Coast?

Q. If a permit is issued to you to work in the Atlantic, please describe what you plan to do: how large an area totally, where specifically would you survey off the coast of North Carolina, how close to shore? Has Spectrum or any company in the industry surveyed an area as large before at one time?

I’ll take the last question first, and the answer is yes. If you go and look in Mexico at what’s been done in the last 12 months, the whole Mexican side of the Gulf of Mexico has been acquired (that is, acquire a surveyor and the data) at once. Yes, there are larger programs – we’ve done some quite large ones. Yes, there have definitely been surveys as big or bigger.

How far away from coast? A lot of that is going to depend on what the final permit says. Because what came out of the PEIS (Programmatic Environmental Impact Study) BOEM will take recommendations from NMFS (National Marine Fisheries Service) and they can maybe alter that. Right now, our plan is to come in to about the 30-meter depth water, so almost 100 feet of water is the limit towards the shore. And that depends on how quick the water drops off, on what the shelf looks like on where that is. So it’s almost about the bathometric contour. It comes pretty close in North Carolina. So we have had some discussions with NMFS about pulling that distance farther off, so I would say, 20-30 miles if the bathometry drops pretty quick we may be a little bit closer, but in general terms, it’s probably 20 to 30 miles to the shore.

Q. And what about the perimeter of the entire area?

What we have is a grid that is from Maryland and it incorporates part of Florida, basically the central Atlantic area and it’s a grid that originally was permitted with say 36,000 kilometers – reduced down to more a regional work to 15,000. So the lines might be parallel lines that run from the coast and go out 4,000 meters – go out deep – and then there’s going to be lines that are perpendicular that we call strike lines that are more or less run along the coast and those are probably 20 kilometers apart – maybe 40k apart. Those will be finalized when we see the final permit.

Q. When are you expecting to get the Incidental Harassment Authorization permit?

This month, next month – we may not get that. We as a business – ourselves and other companies – we look to do work all around the world. Some of them work out, some of them don’t. Again, this survey may never happen.

Q. What will you be looking for?

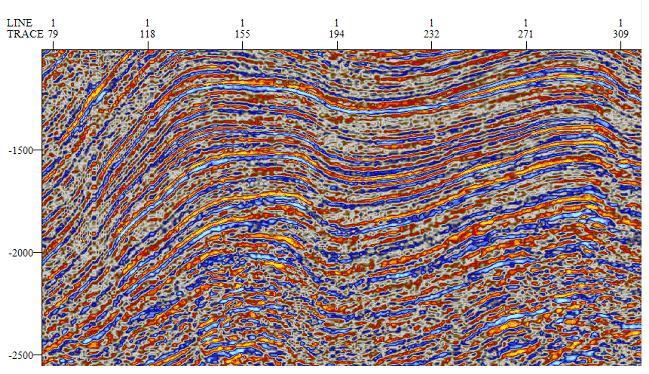

Just a regional geologic picture. You can take the wells that were drilled before and somewhat correlate what sections you’re in. But you’re looking for a regional framework to understand what we call the basin. You’re looking for the different layers beneath the ocean bottom. Nothing specific – with the regional 2-D grid you’re not going to find oil or gas with one 2-D line in this day and age.

Q. Is this technology – say, two arrays dragged behind a boat – done like a lawnmower, covering a whole area? Or is it done by looking at charts and going to specific spots?

I haven’t heard that before – I’m going to use that. We’re going to leave parts unmowed. We’re the bad lawnmower guy. So we’re going to start down the curve. Then we’re going to go in five tracks of where the lawnmower should have gone, and then we’re going to come back the other direction. And then we’re going to go up and do the same thing and go up your lawn in the same direction. We’re going to shoot a grid. You shoot out one line, and then you ‘re cutting that. Then we would turn left and then we come right back into the coast. Then you do a line change. Just turn and then you go back up to the line, back offshore.

Q. Do you have more interest in areas north of Cape Hatteras – the Point – where Mobil Oil and Chevron USA were focused in the ’80s and ’90s?

No, ours is more regional. If you were looking for that area, you would be what we call prospect-oriented. We’re looking more regional – trying to understand the regional framework. That helps you understand the whole – if there is a petroleum system. It’s a regional look. An example for that would be we’re pulling the X-ray through the bottom of the ocean floor. Where Manteo is a gas discovery – you would need to do a 3-D seismic, which is many lines close together – it’s like a MRI. You get a block. So we’re not doing prospect-specific acquisition.

Q. Is there some point in time where that would be done? When would it be appropriate to look more for the prospect?

You won’t see anything like that unless there’s a lease sale. So there’s nobody that’s going to be in that close looking … nobody’s going to be out there shooting 3-D, it makes no economic sense. You could shoot 2-D, but it’s been kind of proven that there’s something there, so you’d want to shoot 3-D.

Q. When do you expect to start, and how long would it take to complete?

If everything fell in place, probably in September. You would probably want to wait until summer is over. It would take four or five months. General rule of thumb is you acquire 3, 000-4,000 kilometers a month. With a 15,000- to 18,000-kilometer program – maximum six months.

Q. When would you be off the N.C. coast, and how long would you be working off the N.C. coast?

I can’t answer that – until we see what the permit looks like. Depending on what time of year and fishing seasons, there’s so much coordination to do, we can’t pinpoint it. You might find you’re off of North Carolina one day, acquiring one line and we decide to go further south because there’s fishing activity or some other environmental activity that we move south and go toward Florida and work two months and come back. It’s too early to start planning on. It would be very nice to start a program and go up a line and down a line like you were weaving in and out, but in the real world it changes. It’s something that we would work with the local stakeholders where we’re going to be once we get closer – if we get down to that point.

Q. How does this type of testing provide a clearer understanding of the undersea oil or natural gas prospects? Does it reduce the number of “dry holes” that the exploration companies may later drill?

That’s a good question. The technology in the oil and gas industry is getting better every day. It’s not unlike telecommunications and the medical field. If we look at what was acquired in the ’80s, that’s when there was MS-DOS (Microsoft Disk Operating System) running on PCs. Remember the Motorola bag phones? Just like that, our technology has come a long way. So that’s we would expect – to be able to image the subsurface cleaner and deeper than what’s out there right now. The process that we’re going through – especially a regional grid without a lease sale in sight – I think all seismic helps eliminate dry holes. But what you would see in a normal cycle, if there was ever a lease round, is there would be 3-D data acquired as well. It significantly reduces the number of holes drilled, whether they’re dry or successful. That’s been a huge cost savings to the business.

Q. How will Spectrum address possible conflicts with commercial and recreational fishing, particularly offshore fishing tournaments and commercial seasons? Will fishermen be allowed to fish while you are working? Is there a general expectation that all survey companies will coordinate with fishermen and boaters and other users?

I can speak for Spectrum, but not the other guys. We all work the same. For one, there’s going to be mitigating factors that we all have to work to.

This is some of the misinformation that was thrown around early on. There’s not going to be six boats or nine boats at one time working off of North Carolina at the same spot. Or in South Carolina or Georgia – it doesn’t matter. There’s not going to be nine companies that go out and acquire a survey.

The way our business works, it’s very capital intensive. It’s an investment that the companies make, and it’s usually one or two companies that work – when you get funding from different sources and you go out and acquire the program. So, even though there may be two boats within a year that are working off North Carolina, they’re going to have two different style programs going on. I guess my point is there’s not going to be a whole bunch of boats out there at one time – the market doesn’t allow that.

About the stakeholders, the fishermen, commercial and recreational, we’ve had discussions with the state, which gave us the lists. You stay away, you go farther offshore. So during those weekend tournaments, for one, you’re communicating (with the stakeholders.) Find out where a tournament might be.

And then, there are facilities to communicate with fishermen. And you work around them. There’s nothing to keep anybody from fishing while we’re working. More than likely, we’ll move out of the way, or we’ll talk to the fishermen and we’ll find where they’re going to be, when they pick up their gear, when they go in. Then we’ll go in there and work. So there’s lots of different ways to do it.

The key word there is communication – there’s got to be a two-way communication.

Q. How do you plan to coordinate with the other survey companies working at the same time in the ocean?

That’s standard. With other survey companies, there are mitigating factors where we can’t get within certain distances of each other. We email each other You communicate multiple different ways.

Q. What will it cost and who will pay?

I can’t really give you a number on that, but that’s an investment; that’s our business model. We call it multi-client data. I think that’s what everybody that’s applied for a permit has in mind. It’s like the movie business – they go out and spend all this money on a movie with the hope that somebody else is going to come in and look at it.

That’s how our business is. We try to get the E&P (exploration and production) businesses to pre-fund the surveys, and with that it helps us finance our surveys.

Sometimes, we’ll take the risk, sometimes we’ll get funding from those companies. It really depends on the economics of a certain area – there could be areas where our business model would take 100 percent risk. There are other areas where you’d want to get almost your whole program paid for before you started. In this case, we wouldn’t start unless we had people helping people pay for it.

Q. I assume that would be the oil and gas companies, and you have them in line

No, no. That’s who it would be, but none of that is in line yet. That’s where I keep going on – there’s a lot of metrics to still fall in place to make this thing actually happen.

Q. What do you do with the information after it’s collected and analyzed? Who will buy it? Does BOEM get the data as well? I assume it’s not just raw data?

No, we process it. Then it comes out in a standard format that’s loaded into work stations that have software that read it.

Q. Who would buy it – the oil and gas companies?

Yes, and then we’re also required by our permit to also give BOEM a copy.

Q. So the government is not paying you for the data, but they’re providing support for you to work in the public resource – is that the exchange there?

We have an exclusive with the government for 25 years before they can actually disclose the data publicly. Anything in the studies they can disclose, but the actual data they have to keep confidential. It’s because of the commercial value. We’re not trying to hide anything. It’s we’re trying to make our investment back.

Q. How long does it take to do that process – doing the survey, analyzing the data and getting it in the hands of the client?

It would be say, four to six months to acquire the program. Another four to six months to process the data.

Q. How would you describe the volume of sound the animals would encounter and will people hear and/or feel the blasts?

No one will feel or hear the blasts. We’re going to be so far offshore. And there’s been no documented impact to marine mammals ever with use of this technology. We stand by that. It’s a safe science we’ve used around the world for 40-50 years. We see no impact to marine mammals. And a lot of that is due to the mitigating factors the governments put on the surveys – acoustic exclusion zones, visual monitoring by observers, halting air gun use, passive monitoring by microphones, ramping up air guns.

Q. How would you describe the sound? Some have described it as loud as a jet engine.

It makes some sound, but I’ve worked on the boats for five years when I first got out of college. You sleep on those boats for two months at a time. So it’s a thud.

You have sound in air and you have sound in water. I can’t tell you what they (the marine animals) are going to hear. Unfortunately, we can’t talk to them. It’s a sound that dissipates extremely quickly. And by use of these mitigating factors, you’re keeping these animals out of any potential impact.

Q. Does the testing have the potential to harm or drive fish away? Concussive noise is believed by some biologists to scare schools of fish and change their behavior. If so, how do you plan to mitigate for that possibility?

If you look at the Gulf of Mexico, it all happens together: seismic, oil and gas and fishing industries. And they’re still catching a bunch of fish. We’re not expecting any effects. We don’t see that impact at all. Ships impact fishing. So if we’re coming through there, I would imagine they are going to get out of the way a little bit. But they’re going to come back to where they were, just like when a ship passes through. That’s something I’ve never seen a study of. It would be nice to have a Go-Pro (camera) put on a fish head.

Q. Do you expect animals to be harmed under the definition of the federal Endangered Species Act? If so, how many “takings” do you estimate will result during the surveying?

We don’t expect any harm to any wildlife during this operation. We don’t see it anywhere around the world. The problem with this information and what is out in the public is the word “take.” The word take under the ESA is very gray. It doesn’t explain exactly what a take is. A take is the same as a ship sailing down a line and fish or marine mammal moving out of the way. I’m not even talking about a seismic ship. But that is a take – you’re altering the behavior of that animal. So based on what we had to follow on our permit with the regulations that were in place, and the modelings that were done, these takes are calculated. They’re not, by no means, an exact science. It’s modeling. But in general operational experience, we don’t expect any takes. You don’t hear of a survey happening and then the fishing stopping.

Q. Sonar used by the Navy has been associated in the past with causing strandings of marine mammals. How is 2-D seismic different?

It’s a completely different technology. Do you how much seismic is acquired off the coast every year, every summer? There’s seismic acquired every summer off the East Coast – there has been for the last seven years. The universities do it. Now, they don’t have to get an IHA. It’s the same equipment, the same technology. And we don’t see strandings. A lot of it is they are doing geologic research, the canyons, near-surface … They’re out there every year. Same technology and everything.

Q. Environmental groups such as Oceana are pushing the Obama administration to delay or cancel seismic survey work in the Atlantic. Part of the argument in favor of waiting is the likelihood of improvements in seismic technology, such as a marine vibrator, that could prevent possible damaging effects to marine mammals and fisheries. What is your view on the future of improved technology?

The marine vibrator is not a commercial unit and it won’t be in the foreseeable future. I’m talking five or 10 years out. There’s no money to spend on it. This is a typical Oceana distraction. If you saw the hydraulic hoses attached to a marine vibrator, you’d be pretty scared. What a marine vibrator does is shake. It has its own issues. The technology we use is safe now. If we could develop one, it would’ve been already working. They’ve been talking about this thing for 20 years. But I don’t see it being commercially, or even in R&D mode, I don’t see it being developed.