TOPSAIL BEACH – The sand in Banks Channel is the pristine, just-right-in-texture kind of sand Topsail Beach wants pumped onto its beach.

The channel has been the go-to sand source for beach re-nourishment projects, and town leaders are aiming to further secure their preferred source by asking the Army Corps of Engineers to tap into a federally restricted area.

Supporter Spotlight

Nearly two million cubic yards of sand dredged from the channel has been pumped onto the town’s beach within the last five years.

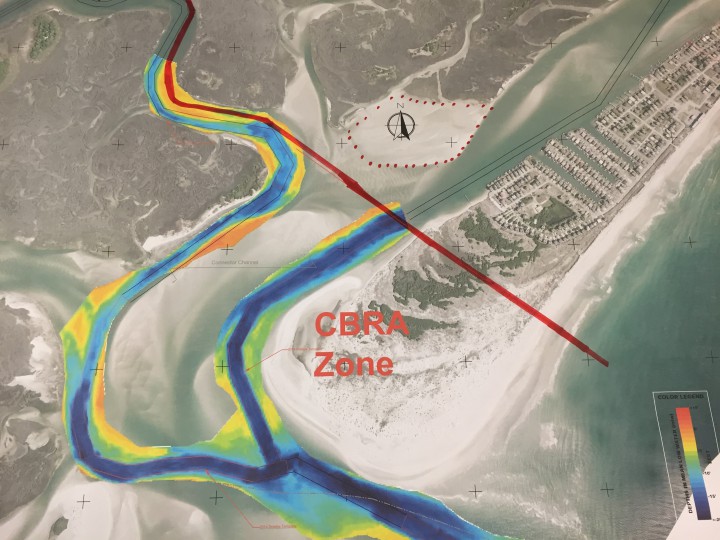

More than half of that sand was from a federally designated Coastal Barrier Resources Act, or CBRA, zone.

Pronounced “cobra,” these areas were identified by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and established by Congress in 1982 to discourage development by removing federal incentives, including federal flood insurance, on storm-prone barrier islands.

There are, however, exceptions on when federal money may be paid out for work in these zones.

Topsail Beach commissioners last October agreed to give the Corps $5,000 to review data about sand in the channel within a portion of the CBRA zone.

Supporter Spotlight

The information the town provided was to aid the Corps in determining whether the sand in the CBRA is the right quality and if there’s enough to designate it as a borrow site.

“It makes so much sense to do it this way,” said Chris Gibson, coastal engineer and president of TI Coastal.

Such a request will have to be made to the Fish and Wildlife Service. The project manager with the Corps did not respond to a request for comment.

Emily Wells, a fish and wildlife biologist with the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Raleigh Ecological Services Field Office, stated in an email that the agency cannot officially answer whether an exception would be allowed in Topsail Beach’s case until the Corps pursues the request.

‘The project’s purpose and need would need to be clearly explained … the Corps and the Town would need to come to agreement on what the project actually is, and then present that to FWS to see if it will meet the exception.’

Emily Wells, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Any federally funded project within a CBRA zone has to meet specific criteria to be considered for an exemption.

The Corps has to prove a project within these zones will be done to maintain federal navigation channels, including the Intracoastal Waterway, or building improvements to structures such as jetties, “including the disposal of dredge materials related to such maintenance or construction.”

This type of work may be done in channels and on related structures that were authorized before they were included in a Coastal Barrier Resources System.

“The project’s purpose and need would need to be clearly explained,” Wells wrote. “If the main purpose of the project is to do maintenance dredging of the channel for navigation purposes, and the sand needs to be placed somewhere because of the navigation project, then that is one scenario. The need for sand that would trigger a navigation maintenance project is another scenario, and is not the same thing, so the Corps and the Town would need to come to agreement on what the project actually is, and then present that to FWS to see if it will meet the exception.”

Millions of dollars in federal, town and state funds have been spent since 2011 on three projects to unclog heavily shoaled areas of the inlet and place sand removed from the channel onto the beach.

Roughly $3 million in FEMA funds the town collected following Hurricane Irene in 2011 covered the entire cost the town’s 2012 project, which included re-nourishing the beach with 169,000 cubic yards of sand within the CBRA zone.

The most recent dredging project, which was finished April 1, 2015, received about $3.7 million in FEMA funds. About 750,000 of the 835,000 cubic yards of sand pumped onto the beach during that project were removed from the CBRA.

The town’s hook to reeling in their request is this: re-nourishing with sand from the inlet is cheaper – significantly cheaper. And, it’s better for the environment, Gibson said.

“The main reason it would be so much cheaper is because of the method of dredging that could be used and where the dredging occurs,” he said.

Offshore dredging is substantially more expensive – about double the cost of inlet dredging because ocean dredges are more expensive to operate, Gibson said. Offshore dredging is also typically disrupted by weather delays than operations that occur within an inlet.

Gibson said engineers know where the peak shoaling areas are in the channel so they could use those areas to pull the highest quality sand.

“The material is significantly higher quality, which means it’s going to erode less,” he said.

Then, there are the rocks or, at least, the possibility of rocks.

Onslow Bay has an abundance of rock bottom, a fact Topsail Beach’s neighbors on the north end of Topsail Island know all-too-well after a beach re-nourishment project there pumped tons of rocks onto a portion of their beach.

Jerry Patton, chairman of Topsail Beach’s Beach, Inlet & Sound Committee, said that what happened in North Topsail Beach “has to be a consideration” when looking for suitable sand sources.

“Clearly the quality of the sand in the inlet is really good because that’s where a lot of our beach sand ends up,” Patton said. “We’re just trying to facilitate a conversation between the Corps and Fish and Wildlife to use that sand.”

Topsail Beach is interested in a designated sand source within the CBRA only if beach renourishing were to be part of future federal projects.

That may be a tough sale since federal funding for beach re-nourishment projects has essentially dried up.

Gibson likes the odds though.

“The way everything is done in Congress it’s all done on a cost benefit ratio,” he said. “We’ve got a method here that we’re saying if you use this method you can reduce your cost by 50 or 60 percent. That’s going to get the attention of Congress.”