This is the first of two parts. The story is reprinted with permission from Bit + Grain, a new website devoted to telling the story of North Carolina – its people, places and culture.

Photos By Baxter Miller

Supporter Spotlight

A casual conversation about our coast can quickly unearth more controversial topics than your average holiday dinner. From Wilmington to Corolla, the most challenging issues of our times — gentrification, food justice, race, socioeconomic inequality, climate change, oil, corporate responsibility and sustainability — coalesce in towns built along North Carolina’s sounds and coast.

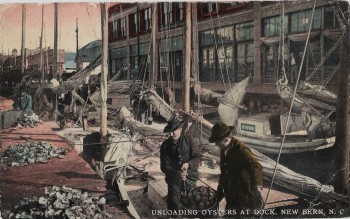

The natural beauty of that landscape, and the seafood and recreation that it offers, has drawn people east for ages. From Native Americans and early European settlers to today’s shrinking number of commercial fisherman, our rivers, estuaries, and the Atlantic herself, have provided a way of life for communities for centuries.

Rising sea level, pollution and development threaten the future of our coast. Efforts to sustain and revive local economies and traditional ways of life are met with many challenges, and are in fact, severely political.

The Oyster’s Story

Nothing tells the complicated story of our coast like the oyster. Crassotrea viriginica, or the Eastern Oyster, is North Carolina’s native species. Naturally a filter, the Eastern Oyster can process up to 50-gallons of water daily. Symbolically, it’s a prism that refracts details about how our state’s economy, environment and culture have evolved since the Civil War. Wrapped up in it, is a story about our coast’s past, present and future.

European settlers reported seeing vast oyster reefs off North Carolina’s coast as early as the 16th Century. In 1586, scientist Thomas Harriot observed an enormous oyster reef off Roanoke Island: “There is one shallowe sounde along the coast … where for the space of many miles together in length and two to three miles breadth, the ground is nothing else.” In A New Voyage to Carolina (1674-1711), explorer John Lawson noted that, “Oysters, great and small, are found almost in every creek and Gut of Salt-Water, and are very good and well-relish’d.” Shellfish mounds on Hatteras Island, Harkers Island and Shackleford Banks indicate oysters were a part of Native American foods long before European contact.

Supporter Spotlight

As North Carolina grew, so did demand for our oysters. The state began legislating the harvest of oysters in 1822, a landmark step in North Carolina’s fisheries regulation. In 1858, a new law awarded fishing rights to residents who enclosed, seeded and harvested estuarine ground for artificial oyster beds — a program that gave rise to our modern-day lease program. Oystermen created 52,000 acres of private oyster gardens in the three decades that followed.

After the Civil War, state leaders turned to oysters, among other natural resources, to rebuild an economy crippled by war. Oyster houses and canneries proliferated, as did irresponsible harvesting practices. Oystermen from near and far wanted in on North Carolina’s oyster boom and those without a stake in maintaining oyster stocks indiscriminately harvested them. In 1891, the legislature declared war on out-of-state harvesters who collected oysters with motorized dredges leading to a period now called the “Oyster War of 1891.”

The industry and harvest levels peaked around the turn of the century when oystermen landed 800,000 bushels — 5.6 million pounds of meat — in 1902. But, years of abundant harvest, came at a cost. Aggressive harvesting, without responsible replacement, critically depleted oyster stocks and habitats. Around that time, courts began ruling in favor of people who argued that access to the bounty of these waters fell under public trust doctrine, which grants permission for the public to navigate and harvest from among other things, sounds and oceans. In the decades that followed, storms, as well as agricultural and industrial pollution, continued to damage oyster habitats. In the 1980s, disease wiped out much of the remaining oyster population. Despite sporadic restoration efforts to build and reseed oyster reefs, wild oyster stocks in North Carolina are nowhere near what they once were and are considered a species of concern by the state Division of Marine Fisheries. Erin Fleckenstein, a coastal scientist and regional director of the North Carolina Coastal Federation, says that presently, “We are still at about 10 percent of historic harvest levels.” Because of low stock, most oystermen today can only count on wild oysters for seasonal, supplemental income. The economic heyday of wild oysters has passed.

A Rebirth

The wild oyster populations of other east coast states have experienced similar challenges. According to NOAA, Virginia’s current wild harvest levels are 1 percent or less of historical levels. But unlike North Carolina, Virginia has created a $55.9-million-dollar shellfish aquaculture industry, over 30 percent of which come from oysters. These oysters are raised by a new generation of oystermen who’ve who have embraced mariculture, a type of aquaculture where organisms are cultivated in open water.

Oyster mariculture, a practice dating back to ancient Rome, can be done in several ways with varied degrees of intervention. The N.C. Rural Center defines the mariculture spectrum broadly: oyster bed restoration and sanctuary development are considered the most passive interventions while active “farms,” which Virginia has built a booming industry around, the most intensive. For these farms, the state grants private leases to public waters, where seedling or “baby oysters” are raised to maturity.

Great strides have been made in our state to address the first level of mariculture intervention –restoration of wild oyster habitats, but Fleckenstein says “There is still work to be done to restore reefs. They are important and critical,” she explains. “They may not be quite as bright and brilliant as the coral reef of the Caribbean, but they are just as important at creating the structure in our sound and creating a habitat for other commercially and recreationally important fish species.”

Intensive intervention, such as mariculture farming, has garnered significant attention for its potential economic and environmental benefits to North Carolina. It’s something our neighbor to north, Virginia, embraced a decade ago. And while North Carolina has made progress in oyster farming, Jay Styron, owner of Carolina Mariculture, says, “We are so far behind right now, it’s crazy. It’s really sad to know that we have this much potential and resource.”

Styron is assistant director of Marine Operations at the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s Marine Science Center by week. He started Carolina Mariculture seven years ago when there were only a few active growers.

“I knew I wasn’t going work for the state forever and this is something I could set up as a retirement job,” he says.

He and his wife, Jennifer, travel from Wilmington to Cedar Island every weekend to tend to the one acre they are actively farming.

Also a Cedar Island native, Styron vividly remembers the heyday of oysters on our coast. “Growing up here I can remember we’d have community oyster roasts for fundraisers and stuff, and people would go out and catch 15 to 20 bushels per person a day and you’d have a dozen people doing it,” he recalls. “There were just mounds of oysters. But they just aren’t here anymore.”

Oysters Good Business

He hopes mariculture can change that. “Oysters clean the environment, put people to work and put money in the economy. To me, it’s a win, win, win,” he says. “The technology is there, the demand is there — now we just need growers.

“This isn’t rocket science.” Styron continues. “We get (the seedlings from hatcheries) when they are 1 to 2 millimeters in size. You can hold 100,00 oysters in your hands. When we get them that small, we put them in the water in small fine mesh bags. As they grow and get bigger they are sorted into larger mesh cages. You are trying to get them in the largest mesh you can because the larger the mesh, the more water flow, the more water flow, the more food, the more food, the bigger the oyster. So you are always grading and sorting the oysters out.”

Farm-raised oysters offer a completely new product to North Carolina. Unlike the wild oysters that grow in clusters, those raised in cages are produced mainly for the half-shell market, which values individual oysters consistently uniform in shape and size. “While oysters on the half shell are worth three times the value of a wild oyster, it doesn’t affect the market for wild oysters because they are different products,” says Styron. Even the quantity in which they are sold is different: these “single selects” are distributed in bags of 100 instead of by the bushel.

Farm-raised oysters are also harvested year-round, whereas wild oysters can only be harvested between mid-October and the end of March; a rule many of us know by “You only eat oysters in a month with R.” Grounded in reality — though you won’t become physically ill from eating a wild-caught oyster outside of the traditional season — the rule partially arises from the spawning habits of wild oysters. Between April and September, oysters use all of their energy to reproduce, which slows growth and creates an undesirable meat quality.

Mariculture oysters are a non-spawning variety of Eastern Oysters; using selective breeding techniques and capitalizing on a chromosomal phenomenon known as polyploidy, hatchery seedlings are bred to have three chromosomes which can’t reproduce and don’t spawn. Styron explains, “Triploid oysters are same concept as seedless watermelon or any of your seedless fruits and vegetables… So, while wild oysters are putting all their energy into spawning in July, these oysters are just sitting there eating and getting big. Eating and getting big. So ours are just as good in July as they are in January.”

Additionally, while wild oysters take three years to grow to market size, these oysters mature, on average, in 18 months.

Tuesday: Improving the habitat