This story was reprinted from N.C. Health News

RALEIGH — The seasons are getting ready to change, and with the shortening days will come the sight of flocks of ducks and geese flying south for the winter.

Supporter Spotlight

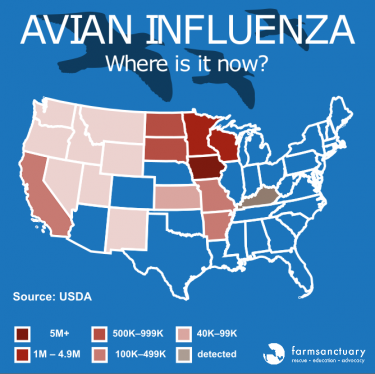

But some in North Carolina are dreading the arrival of our feathered winter residents. For the most part, those are poultry farmers who’ve watched a highly pathogenic form of avian influenza, or bird flu, devastate farms in the Midwestern U.S.

The disease has required the culling of millions of chickens, turkeys and ducks, driving farms into financial peril, affecting the nation’s egg supply and increasing the prices of chicken and eggs.

“We’re literally one flyway away” from the disease, State Veterinarian Doug Meckes told farmers who gathered recently at the annual Food Safety Summit, hosted by state Agriculture Commissioner Steve Troxler at the state fairgrounds in Raleigh.

Poultry experts believe the disease has been carried to farms large and small by wild migrating birds. For the past three months, those birds have been congregating in summer breeding grounds far to the north, passing the disease around. As birds return south from Canada and Alaska, they could very well bring the disease with them.

And while high pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI, is not a human health issue per se, spread of the disease could affect the supply of meat and eggs and kill poultry on both large farms and in backyards.

Supporter Spotlight

“We’re talking about food availability, and how the high path [HPAI] could impact that food availability,” Troxler said. He recounted how his department fielded calls from the military during the Midwest outbreak this spring asking for help finding eggs.

“Well, no, we can’t help you find them, because they’re not out there,” he said. “We’ve seen them taken out in the Midwest. Egg prices could rise again; there could be a shortage of eggs.

“I do know that the U.S. is importing eggs now for the first time in a long, long time.”

And officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are keeping an eye on these outbreaks, just to make sure they don’t make the jump from birds to humans.

Averting the First Sneeze

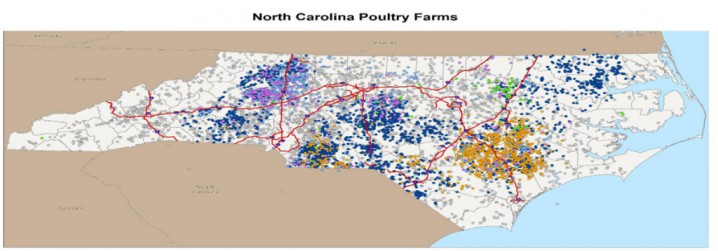

Troxler said he’s serious about avoiding the arrival of HPAI in North Carolina, where poultry is a $34 billion a year industry. The coastal plain is one of the areas in the state where commercial poultry farms are concentrated. All poultry shows in the state have been banned for the year and the State Fair in October will not have any fowl on display, according to Brian Long, a spokesman for the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

“We just cannot afford to risk the movement of poultry after they have come together and back to different geographic locations and are potentially moving this virus,” Meckes said.

He said the evidence is strong that the disease was introduced in Minnesota, Iowa and Wisconsin by migrating waterfowl that carried the virus and pooped it out. It was then carried on the wind.

“But as the virus began to build up in commercial operations, the human factor became a great component of the virus spread,” Meckes said. “People moving from farm to farm without the appropriate change of clothing, without appropriate decontamination and disinfection of their vehicles.”

In prior outbreaks, the spread of infection was traced to virus carried on the tires of trucks from affected farms that then infected other farmers’ trucks in the parking lots of feed stores.

A single case of HPAI can rip through a chicken house within a day or two, sickening or killing many of the animals.

Veterinarian Ben Meade from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service told the group that vaccines aren’t a good choice for stopping the spread of this disease. He explained that as with human flu vaccines, avian flu viruses change frequently, and it can be hard to create the right vaccine in time to stop an outbreak.

“There is a vaccine, but it’s not very good,” Meade said. He also pointed out that many international trading partners won’t buy vaccine-treated poultry for up to a year.

Between 30 and 40 percent of U.S. poultry is for the export market, Meade said.

Large and Small

The Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services has also asked people with backyard flocks to register their birds, a move some birders view with suspicion.

“If you don’t tell the fire department where you are, how can you get help?” Troxler asked, by way of analogy. “And then if you don’t like government, and the fire department happens to be part of government, are you going to sit in the house and burn up?”

He said his department is “pro people having backyard flocks. We just want to make sure that birds don’t die.”

“We had a lady call in, and she said, ‘I’ve got a pet rooster, and he’s old and he stays in the kitchen with me most of the time. He loves to watch things on the Internet,’” Troxler recounted. She wanted to know if her single bird needed to be registered. “We said, ‘Yes, ma’am; we want to make sure Chester is alive.’”

Meckes said agricultural officials were not going to confiscate anyone’s birds

“We just want to know where birds are,” he said, should the disease come this way.

Meckes also said that in the event of an outbreak, part of the containment strategy is to restrict movement of birds in or out of an area; in effect, a quarantine. That also means that farms raising chickens will not be able to raise more birds for months as they disinfect their chicken houses.

Mass Killing

Meckes showed grim images of poultry houses in Minnesota, where North Carolina teams arrived in April to help agriculture officials control widespread outbreaks. To kill the birds, response teams pump tens of thousands of gallons of firefighting foam into the poultry houses. The birds suffocate within minutes.

He said on the first weekend the teams arrived, they went straight to the world’s largest turkey farm: “2.54 miles of turkey houses, 12 houses.” Within days, the North Carolina teams had “depopulated” 305,000 from that one farm, first culling them and then composting them.

It’s the concentration of animals that concerns some agricultural experts, in part because putting together all those birds increases the death toll when diseases strike.

“When you put large numbers of birds in one place, disease is more of a concern,” said Scott Marlow, an agronomist who heads the Rural Advancement Foundation International, based in Pittsboro. “Just like when kids go back to school, the illnesses run through them quickly and they bring home the illness.”

Marlow also voiced concern for the contract farmers who grow the birds for large producers such as Tyson and Perdue.

“We’re very concerned about the multiple levels of losses the contract producers face,” Marlow said in an interview after the summit. “There are the costs of disposing of animals killed, and of being quarantined and facing weeks and months out of production. Those contractors have loans taken out to run these farms. You get (HPAI) in your farm, it could mean the loss of income, the loss of farms, the loss of homes.”

Requirements from the USDA and the International Organization for Animal Health call for cleaning and disinfecting regimens that could take a chicken house out of production for as long as six months.