It’s only fair.

That is the sentiment of coastal states, where politicians say that providing infrastructure and expanding public services to support offshore oil and gas development deserves a cut of the multibillion-dollar pie.

Supporter Spotlight

Last year, companies paid $7.3 billion in royalties to the federal government for oil and natural gas drilled at least three miles from shore.

But if oil or natural gas were now being produced in federal waters off the N.C. coast, the state wouldn’t receive a dime. For the state to cash in, Congress would first have to change the law.

With the possibility of the first lease sale in the Atlantic six years away, Republican Gov. Pat McCrory and U.S. Sens. Thom Tillis, R-N.C., and Richard Burr, R-N.C., are joining a chorus of coastal states pushing to secure a share of federal oil royalties.

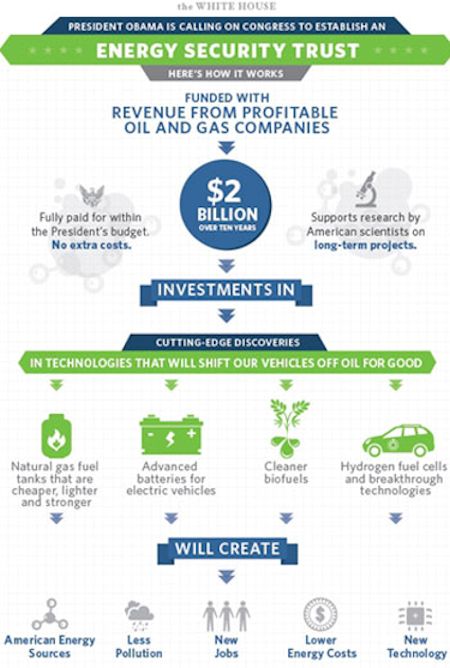

Their efforts thus far have been met with opposition from the Obama administration, which included in its draft budget plan this year a proposal to spread offshore revenue sharing among all states. The oil and gas are on public property, the administration has argued, and thus any federal fees collected from private companies that drill for it should be used to benefit all taxpayers. Some of it, for instance, could finance research of alternative energies, as Obama has proposed.

Supporter Spotlight

Qualifying coastal states have for years received 27 percent of federal oil subsidy revenues generated from offshore production within the first three-mile stretch of ocean seaward of state coastal waters.

The administration would like to replace that deal with a broader sharing proposal and do away with the arrangement Congress approved in the 2006 Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act, which broadened the area where states receive a cut of federal shares. The law shares 37.5 percent of bonus bids, rentals and production royalties with Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas.

Alaska’s exclusion from the deal stiffened tensions over offshore oil production in that state.

“It’s very contentious,” said Jim Stouffer, Alaska Department of Natural Resources royalty accounting manager. “What’s on shore, the feds have tied up much of the land so that we can’t even drill on it. It’s our lifeblood. Over 90 percent of our general fund revenue is in oil and gas. Royalties amount to about 40 percent.”

Alabama, Alaska, California, Louisiana and Mississippi take home all of the royalties for oil and gas extracted within their state waters, which extend three nautical miles from shore. Texas’ and Florida’s waters extend to nine miles offshore.

Revenues disbursed from federal royalties have been significantly less than what Texas receives from shares in its state waters. In Texas, about $1.2 billion was collected in revenues generated within state waters last year, according to Jim Suydam, a spokesman for the Texas General Land Office. The state received about $1.5 million last year in federal offshore royalties, according to the U.S. Office of Natural Resources Revenue.

Yet in North Carolina much emphasis is being placed on federal oil royalties expected if drilling occurs off the coast – so much so politicians say they will not support drilling if the state does not get some of the money.

“It is incumbent upon me to take the costs and benefits into account when considering whether to support offshore activity in North Carolina,” McCrory said in an April 15 statement to the congressional Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources. “Considering these facts, North Carolina will not support offshore energy development without revenue sharing.”

Revenue sharing would be vital to “frontier” coastal states and beach communities in the new areas of energy exploration to help offset spending on infrastructure, services and the implementation of environmental-protection measures, he said. McCrory’s office did not respond to interview requests.

Meanwhile, Tillis told CRO the economic benefits would bring relief to N.C. taxpayers.

“We’re talking about billions of dollars of revenue over time that can be used to reduce the tax burden,” Tillis said in a telephone interview. “In many ways North Carolina, because we already have such a diversified economy, it could create one of the most diversified economies in the nation. It is a long-term process. In the statutes we have to create how they would be allocated so that we would get the distributions right.”

Tillis is one of five cosponsors of the Southern Atlantic Energy Security Act, a bill recently introduced by Sen. Mark Warner, D-Va., to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. The bill allocates half of offshore revenues to the federal treasury and the remainder to Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia with each state receiving not less than 10 percent of available revenue. States would have to use 10 percent of the money to enhance land and water conservation efforts, improve public transportation, establish alternative energy production and enhance beach nourishment.

“I think that the majority of people in Congress support this not only for the economic benefit but for the strategic benefit of creating a greater stream of revenue,” Tillis said. “The challenge is whether we have an administration that’s willing to enter into that dialogue.”

In response to CRO’s query, Burr’s office released this statement: “Senator Burr is continuing to engage coastal communities on exploration and believes that revenue sharing much be channeled specifically to our communities along the coast to provide for beach re-nourishment and other important priorities. Senator Burr is committed to ensuring that any exploration off our coasts would protect our coastal communities and our vital tourism industry.”

Warner’s bill and two others aiming to open more federal waters to oil and gas production and allocate those revenues to states were met with a cool reception from the administration, according to media reports.

The bills are the latest in a lengthy battle over oil revenue allocations.

“Basically up to now we haven’t really seen a lot of federal royalties,” said Patrick Courreges, a spokesman with the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. “Starting in 2017, that’s when there would actually be some money. It’s capped, but it’s more than pennies.”

Revenue amounts fluctuate based on offshore activity and the price of a barrel of oil. Lower production and oil prices equate to a decline in revenues.

An American Petroleum Institute-funded Quest report released in December 2013 projects offshore oil and gas production resulting from opening the Atlantic outer continental shelf will generate as much as $51 billion in total cumulative economic benefits to the country from 2017 to 2035. East Coast states would be the biggest recipients of the economic benefits, especially those from capital investment and jobs, according to the report, which also assumes Congress will change the law and that federal revenue shares would be split 37.5 percent to the states. Those states would receive a combined estimated $4.5 billion a year by 2035.

Revenue sharing is the big assumption here, but industry proponents say even if the law isn’t changed, it shouldn’t be a deal breaker for offshore drilling in the Atlantic.

“People get so focused on the revenue sharing and that’s important,” said David McGowan, executive director of the N.C. Petroleum Council. “With the revenue sharing, that’s money paid directly to the state government. You see it. The direct and indirect economic impact, it’s obviously a little more nebulous. That’s really where the most significant benefits lie for the state. Even without that revenue-sharing agreement, taking the Quest numbers at value, it’s still $4 billion a year.”