Reprinted from the Island Free Press

OCRACOKE – In this time of Instagram and email, when communications are reduced to micro-seconds, it’s hard to image a time when people actually wrote letters that took days, maybe weeks to get to their recipients. If you lived on Ocracoke Island, the only way to send or receive that letter was by boat.

Sponsor Spotlight

“We always waited for the mail boat to come in,” recalls Della Gaskill, remembering when she was a girl growing up on Ocracoke. That was something that we enjoyed, going and seeing the people who were on it, because it carried some passengers and also some freight for the island people and for the stores. We enjoyed doing it just to get away from home and see what we would get that evening in the mailbox.”

According to Elizabeth Howard, Ocracoke’s postmistress in the 1940s and ‘50s, “when the mail boat used to come in, everybody that could get down there, and who had the time, would show up. They were anxious to see who came, to see if they had gotten any mail and to see their friends and relatives who would also be there.”

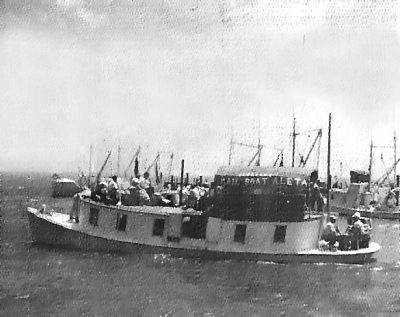

The Aleta carried mail and passengers between Ocracoke Island and Atlantic in Carteret County during the 1940s and ‘50s, and was, in the words of a Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum press release, “central to coastal communication.” A round trip from Ocracoke to other islands and back could take up to 10 hours.

Today Ocracoke’s beloved mail boat lies at the bottom of the South River in mainland North Carolina, no doubt providing a fine habitat for fish and other marine life. She lives on, however, in the memories of those who once peopled her decks as they traveled to and from Ocracoke or gathered on the dock to greet her, collect their mail and welcome the passengers she carried. She lives on in books that describe her short but memorable history, and now she is the focus of a new exhibit at the Graveyard of the Atlantic Museum in Hatteras.

Sponsor Spotlight

The exhibit, entitled “With Love, Aleta,” will open on April 1. It is written as a story, with Aleta speaking in the first person about the era when she delivered mail to the island. While the text is written on the fourth-grade reading level, to inspire young people to have a self-guided museum experience, the exhibit appeals to people of all ages. It introduces people to historical topics, making them relevant to every day. It consists of more than 40 panels, including vintage post cards and “mail art,” created by people who still love old-fashioned “snail mail.”

“With Love, Aleta” provides a backdrop for Sandcastles, a maritime craft program offered weekly from mid-May through September that will focus on communication this year. It is, according to Mary Ellen Riddle, education curator at the museum, “a perfect way for young folks to wet their feet regarding maritime history and culture… It is fun, engaging and relevant to everyday life.” There will be a postcard contest, and winning cards will be displayed at the museum in 2016.

The story of the Aleta is an interesting one. Much of the following information is from Ellen Marie Fulcher Cloud, whose father was the owner and captain of the Aleta for a number of years, and from island native Phillip Howard, who publishes history accounts on his Ocracoke blog, as well as from other local sources.

The Aleta was built at Atlantic in 1923 by Ambrose Fulcher, for Howard Nelson who, according to Phillip Howard, named her for his sister. Forty-two feet long with a Caterpillar diesel engine, she was similar in design to the shad boats built on Roanoke Island. Capt. Nelson used her to run the mail between Morehead City and Atlantic. Later, when the road was paved to Atlantic and mail carried by vehicle, he sold the Aleta.

During prohibition days, she became a booze runner until being seized by federal agents and auctioned off. Dee Mason of Atlantic bought her to use as a buy boat, transporting seafood.

When Capt. Wilbur Nelson obtained the mail contract in 1938, he bought the Aleta and for six years ran mail, freight, ice and passengers from Morehead City to Ocracoke, stopping at communities along the route as well as Atlantic, Cedar Island, Hog Island and Portsmouth. It was a 24-hour trip, stopping at Ocracoke overnight, before starting the same route back to Morehead City.

A memorable trip aboard the Aleta was described by Dorothy Byrum Bedwell, who lived at Portsmouth until 1940. She wrote in her book, Portsmouth: Island with a Soul, published in 1984, that “the mail boat was not designed for partying, and safety requirements were not as critical then as they are today. Those who imbibed while underway caused real hazards.

“Once…when my mother and brother were making the trip to Ocracoke, a tipsy lady, trying to walk the narrow strip of deck around the cabins tumbled overboard as the mail boat was traveling abreast of the inlet where the tide is most powerful. My brother, an expert swimmer, dove in after her and pulled her back aboard. The mail boat captain was so genuinely grateful for the rescue of his passenger that he assured my brother free passage up and down the sound from that time on.”

At Portsmouth Island, Carl Dixon would pole out to meet the mail boat. Betsy Nelson Bykerk wrote, for a Friends of Portsmouth Facebook page:

“I remember these stops. I’d listen for the Aleta to start chugging down as we got closer to Ocracoke and passing Portsmouth. If I remember right, often times poles would also come out to help with what I only guess was sandy areas that were present as we got closer to Portsmouth. I remember watching the process of the exchange closely and the friendly shouting back and forth. This has always been a very clear scene to me. I was so focused on the Aleta that my mind can to this day picture and feel the memories of getting to sit on top or being in the cabin and the little portholes. The door to walk through and step down and I believe step into a door on the left for the bathroom (potty) or whatever it’s called on a boat and again the sound of the engine and the chug, chug, chug. I can see it, I can smell it, I can hear it. I love these memories.”

In later years, Henry Pigott picked up the mail from the Aleta when she went by on her way to Ocracoke. Ben Salter in his Portsmouth Island: Short Stories and History, published in 1972, recounted what would happen next: “He would pole out in a small skiff, get the mail, any passengers and give the captain a list for groceries for the people on the island. The merchants at Ocracoke would fill the orders and send them back by someone coming over or on the Mail Boat’s next day.”

After it arrived on Portsmouth by skiff, the mail was taken into the village on a wheelbarrow. Lum Gaskill was the last to bring in the mail this way. But finally, “there were only three residents on the Island and the U.S. Postal Service decided it could not justify the expense of delivering the mail to this isolated Island,” according to Ellen Cloud in her 1996 book Portsmouth: The Way It Was. “The entire population (three people) got together and signed a petition to keep Lum from being ‘let go.’ How would the residents get groceries and supplies? How would they get their mail? Regardless of their efforts to keep Lum, their only connection with the rest of the world, the service was terminated.”

In 1945, Elmo Fulcher, who had worked with Nelson as his mate, bought the boat with George O’Neal. A dock had been built at the Ocracoke post office, where the Aleta tied up.

A 1948 article written by Charles Killebrew for the Raleigh News & Observer describes the trip, four and a half hours each way, stopping at Portsmouth Island to serve the 15 people then living there. It described the cabin as small, with comfortable seating for 10 to 12 people, but Capt. O’Neal said he would take as many people as he had life vests for. He carried 60 women one time, he said, and they were “all over the boat.” O’Neal told the writer that he ran every day of the year, missing only a couple for storms, and had never had to be towed by the Coast Guard. He had, he added, on several occasions had to tow them.

Capt. Elmo’s daughter, Ellen Marie, tells this story about her father on her website: “Capt. Elmo was known for his knowledge of the local waters. He needed only the stars or a pocket watch and a compass to navigate the sounds of eastern North Carolina. George Jackson tells about a day that he ran on the mail boat with my father, when the fog was so thick they couldn’t see the bow of the boat. He will be quick to remind you that the trip from here to Cedar Island is a pretty straight stretch, but when you enter Core Sound and head for Atlantic, N.C., there is a lot of turning and winding. He tells how Capt. Elmo used his pocket watch to time his distance from one marker to another and using his compass to set his course for the next marker, blowing the fog horn to warn other boaters of their location. George goes on to tell how he heard the Captain back down on the engine, while giving the boat a turn to the left and idle the engine. He asked Capt. Elmo what was going on and why had he stopped the boat. The reply was, ‘Well George, we’re here, we’re at the dock in Atlantic.’ George stuck his head out of the window, and could see nothing, but he could hear a car running and people talking on the dock.”

Capt. Elmo and George O’Neal continued running the mail route until 1952, after which Ansley O’Neal received the contract, continuing the service until it became obsolete in 1964.

The Aleta docked first at the Post Office and later at Willis’ Store and Fish House, next to the community store. It became a popular place where folks gathered to meet the Aleta. Betty Helen Howard Chamberlain has fond recollections of going there when she was around four years old. Every Sunday after church, she and her mother, Elizabeth Howard, along with most of the village, would go to meet the mail boat. Betty Helen would get a cup of ice cream, and her mother would pour Coca Cola over it, making it fizz.

Says Alton Ballance, an island native: “I can just barely remember when the 42-foot mail boat Aleta used to bring mail to Ocracoke. My father used to run with some of the captains and fill in for them when they had to be gone. I guess I’ve watched it many times pull up to the dock in front of our house and unload passengers and mail. It would leave the island around 6:15 a.m., arrive in Atlantic three and a half hours later, and arrive back at Ocracoke at 4:30 or 5:00 p.m. Some people would get there well before 4 o’clock. While they were anxious for the boat to get there, they didn’t mind killing the time talking to other people and keeping up with what was going on around the island.”

After they stopped carrying the mail, Capt. Elmo bought out George’s part of the Aleta and converted her to a shrimp boat, which he worked until his death in 1979.

The Caterpillar diesel engine in the boat was the oldest one still in operation back in the 1960s. The Caterpillar Co. found out somehow about the engine in the boat and sent representatives to Ocracoke to take pictures and see for themselves that it was actually still a working engine. They published an article about the boat. When asked how he had kept it working all those years, Capt. Elmo replied, “She’s my baby and I work on her every day, wake her up every morning and tuck her in every night.”

The Aleta then passed on to Murray Fulcher, whose son Keith shrimped with her in Pamlico and Core sounds. Murray later tore off the cabin, planning to use her as a run boat for his fish house. He took her across the sound to South River to have work done on her, but the work was never accomplished. She was finally hauled up the river and sunk, and there she remains, the cost of restoring her deemed cost-prohibitive. There is a model of the Aleta, made by George Jackson, at the Ocracoke Preservation Museum, and of course, there is now the exhibit at the Graveyard of the Atlantic.