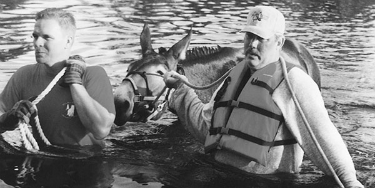

Hurricane Floyd remains the costliest storm in state history and North Carolina’s worst natural disaster. Flooding from the storm drove thousands from their home. Photo: LEARN NC, by Dave Gatley/FEMA News Photo |

First of two parts

For nine days in the late summer of 1999, Tropical Storm Dennis tortured the N.C. coast. It sat offshore pounding the beaches, striking once and turning around to strike again, and soaking a wide swath of the coastal plain.

Sponsor Spotlight

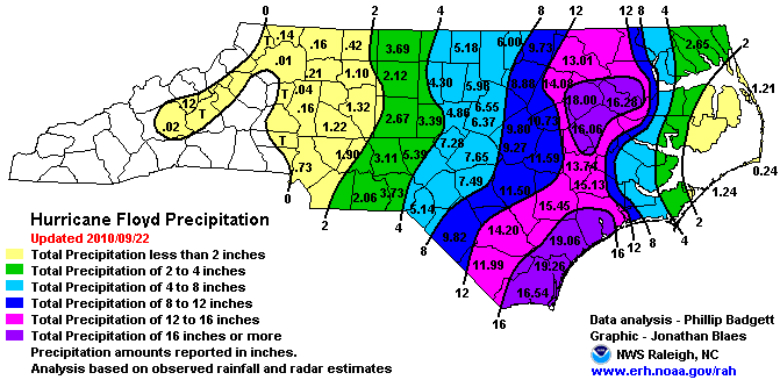

Exhausted and distracted, residents in the coastal counties were ill prepared for the abject devastation Hurricane Floyd would leave in its wake 11 days later on Sept. 16. Coming on the tailwind of Dennis, the storm was said to have flooded the already drenched inland counties with an amount of water that equaled 95 percent of the volume of Pamlico Sound. In some locations, it reportedly rained 60 hours straight.

To this day, 15 years later, Floyd, with $6 billion in damages, stands as the costliest storm in state history and North Carolina’s worst natural disaster.

“It produced the most significant flood events eastern North Carolina has ever seen,” Jim Merrell, a 31-year veteran forecaster at the National Weather Service office in Newport, said in a recent interview.

Rainfall records were shattered, riverbanks rose with terrifying speed and residents in some communities were forced onto their rooftops to escape the floods. Floodwaters crested as high as 24 feet above flood stage along the Tar River. The Neuse, Roanoke, Waccamaw and New rivers exceeded 500-year flood levels, although damage was lower in these areas than along the Tar because of lower population densities. Of the 52 fatalities in North Carolina, 36 were from drowning.

Sponsor Spotlight

“It was something I thought I would never see,” Merrell said. “They had never seen water come up that high.”

Even Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which caused dramatic flooding along the coast, did not come close to the Floyd’s astounding destruction in North Carolina. And Floyd taught the state many lessons.

A massive, fast-moving storm that was about double the size of most Atlantic hurricanes, Floyd made landfall near Cape Fear as a strong Category 2 storm. It churned inland, dumping up to 20 inches of rain in 12 hours. For two weeks, rivers continued to rise. Contents of homes, businesses, fuel tanks, sewage treatment plants, storage sheds, barns, septic tanks and hog lagoons spilled into the floodwaters, transforming communities and their waterways into toxic, stinking cesspools. Livestock and pets drowned or were abandoned by the hundreds of thousands. Waterlogged soil could no longer hold up trees, which toppled in alarming numbers.

This graphic shows the total rainfall in inches from Hurricane Floyd. The areas near the Cape Fear and Tar rivers, colored in purple and pink, received the most. Graphic: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

Jay Barnes, a hurricane historian and the co- author of Faces from the Flood: Hurricane Floyd Remembered, said that Floyd was initially a scary monster aiming for Florida – it was the first storm to close down Disney World. But then it weakened and set its sights on North Carolina.

Its remaining might struck in the middle of the night. One person he interviewed, Barnes said, told him that he wasn’t worried about the storm until he woke up in his bed and noticed that his back was wet.

“That gives you an idea of the shock,” Barnes said. “It was different than a lot of our hurricanes.”

Tarboro, Rocky Mount, Windsor and Wilson suffered more than most, with downtowns inundated. Historic Princeville, one of the oldest black communities in the state, was left completely under water. With remarkable determination, the townspeople have since rebuilt the entire town.

But despite Floyd’s biblical flooding, the state today is tougher and wiser, with better flood insurance coverage, less flood-vulnerable properties, updated flood and storm surge maps and improved emergency communication.

“North Carolina has a history of being very forward-thinking in the way it handles hurricanes,” said Jamie Kruse, director of the Center for Natural Hazards Research at East Carolina University. “I think Floyd gave everyone an appreciation that things can be done better.”

The center held a symposium on Floyd to mark the 10th anniversary of the storm, with numerous scientists giving presentations about issues. After that gathering, Kruse said, East Carolina University established a collaborative relationship with N.C. Emergency Management. The partners conduct a workshop together every May before the start of hurricane season.

“This workshop represents a really good intersection between the academics who study this stuff,” she said, “and the emergency managers who can utilize these findings to do a better job.”

Buster Leverette (left) organized volunteers to rescue hundreds of stranded animals in southeastern North Carolina in the aftermath of Hurricane Floyd. Photo courtesy of Jay Barnes |

In recent years, social media, especially Twitter and Facebook, have become important tools in communicating with the public about storms, Kruse said. It can be a useful way for the public to tell emergency management what is going on, although the information still has to be verified. In the reverse, social media can provide real time updates for the connected public.

Kruse said public agencies recognize that even with the most modern communication tools, information about complex science that would help the public has to be understandable. When it comes down to it, what good will be new storm surge maps to property owners if no one can figure out what they mean?

The Weather Service, for instance, is working with meteorologists to help them improve as communicators, she said.

Other changes that were a direct outcome of Floyd stemmed from the realization that animals are also victims in storms. Many pet owners during Floyd refused or were reluctant to leave their beloved animals behind, creating unanticipated challenges for emergency personnel. There were also countless animals that needed care and homes after the storm. And one of the more horrifying images of Floyd were the bodies of animals that littered the landscape and waterways across the region.

Numerous vulnerable people – frail, ill or disabled – were also forgotten or endangered during Floyd’s chaos.

Now, emergency management agencies gather information before a storm of people who will need assistance, and storm shelters have been set up to make accommodations for pets.

According to a March 1, 2000 article in NASA Earth Observatory, more than 7,000 homes were destroyed by Floyd and 56,000 were damaged; more than 1,500 people had to be rescued and 10,000 were sheltered in emergency housing.

Many property owners had no flood insurance because they inaccurately believed that their homeowners insurance would cover floods.

Since Floyd, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, began buying up the most vulnerable flood-prone properties and established a program to raise other properties on pilings above flood level. With the massive flood damage from Floyd followed six years later by even worse flood damage in Hurricane Katrina, the entire federal flood program is currently being reevaluated and reformed.

The updated flood and surge maps that were spurred by Floyd provide other layers of proactive flood protection. Post-storm analysis by FEMA found that the majority of homes that were lost or suffered damages in Floyd were not correctly depicted in flood maps.

“One of the positive things as a result of that storm is the response of FEMA,” Barnes said. “We now undoubtedly have the best flood plain mapping in the nation.”

Barnes, who is also the director of development at the N.C. Aquarium Society, said that the description of Floyd as a 500-year storm is a term used by meteorologists based on data that can’t predict actual frequency, especially considering changing environmental conditions. But even climate change and sea-level rise – which so far appears to have minor effect on the number and intensity of storms — can’t explain the convergence of factors that make a Floyd.

“Given enough time,” he said, “we could have another storm emerge like Floyd.”

Thursday: Water quality and hog lagoons after Floyd