WRIGHTSVILLE BEACH — Though her depiction isn’t likely to appear in a brochure for tourists, Tracy Skrabal of the N.C. Coastal Federation describes this beach town near Wilmington as “a very small, but impervious town, surrounded by water.”

There, she’ll tell you, lies the problem.

Sponsor Spotlight

The goal of the plan is to reduce the flow of polluted stormwater into Bradley Creek. |

Most problems, though, have solutions, and one is beginning to take shape here behind the fire station, but more on that in a minute. First, let’s look at how we got to where we are.

Development along the shoreline over the years has traded soil, trees and marshes for concrete, asphalt and other hard building materials that have robbed the land of its ability to absorb rainwater. Confronted by these so-called “impervious surfaces,” rain from storms has drained into waterways instead of soaking into the ground. This runoff is poisoned by the detritus of society – excess pesticides and fertilizers from lawns, asbestos from brake pads, oil and gasoline byproducts from vehicles and unhealthy bacteria from animal droppings that have closed areas to shellfishing, and in some cases, even swimming. You won’t find those facts in your average tourist pamphlet either.

“This stormwater runoff,” said the executive summary of Wilmington’s 2012 watershed restoration plan for two local, polluted creeks, “picks up bacteria and transports them… much like a bus picks up and discharges its passengers.”

The plan to clean up Bradley and Hewlett’s creeks is a no-holds-barred attempt to reverse declining water quality and restore these waterways to their original condition. Instead of tackling the much more difficult task of eliminating multiple sources of bacteria — the passengers on the bus — the plan looks to alter the dynamics of the transportation system: In essence, shutting down the bus line and denying the passengers their ride to the water. That water is instead routed to more useful destinations.

No small feat, as a 107-page restoration plan would indicate, but at the plan’s core are two very simple ideas: Increase public awareness through education and find workable solutions. The plan devotes much space to that last item. It stresses the simplest solutions, such as encouraging residents to redirect roof drainpipes away from driveways and sidewalks and toward a garden, lawn or other water-absorbing surface. They could use a bucket, rain barrel or high volume cistern to collect the runoff from the drainpipes. With the addition of a pump, the stored water can then be used to irrigate plants and water lawns.

Sponsor Spotlight

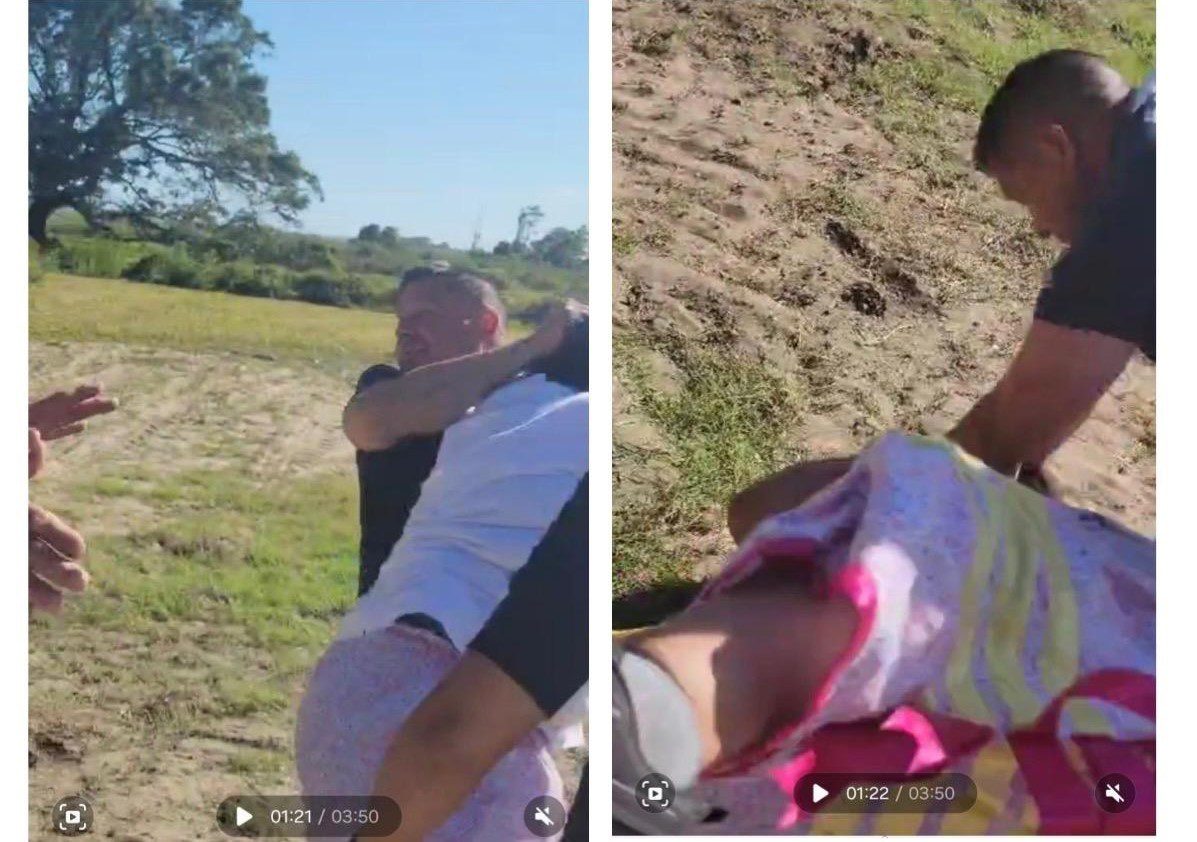

Here the project team gathers in front of a cistern. The team includes staff from N.C. National Estuarine Research Reserve, the University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wrightsville Beach, Wilmington, the N.C. Department of Transportation and the N.C. Coastal Federation. Here the project team gathers in front of a cistern. The team includes staff from N.C. National Estuarine Research Reserve, the University of North Carolina Wilmington, Wrightsville Beach, Wilmington, the N.C. Department of Transportation and the N.C. Coastal Federation. |

Workmen install one of the cisterns. |

The Wrightsville Beach Fire Department has even discovered it can be used to wash fire trucks. That effort has just begun, with the addition of a 25,000-gallon system of cisterns in and around the town’s Public Safety Building, which opened in the summer of 2010.

The point, it should be noted, is not the storage of water for plants or washing vehicles. It is, said Wrightsville Beach’s Stormwater Manager, Jonathan Babin, about “the ability to eat seafood out of Hewlett’s and Bradley creeks again.”

With help from the federation, the town received grants to buy and install five 3,000-gallon cisterns at the Public Works Department. Town officials soon discovered that a half-inch rain easily produces 15,000 gallons of water, filling the tanks to capacity. They applied for a grant extension, again with the federation’s assistance, and bought a 10,000 gallon tank, which was installed just outside the recreation fields, directly across from the Public Safety building. A pump brought the overflow from the smaller tanks to the larger tank. The water from the larger tank is used to irrigate the playing fields.

“The fields were taken completely off the water grid,” explained Babin, “so there’s no aquifer impact.”

Babin reported that 27,985 gallons of rainwater was stored and reused last month alone.

“It makes a big difference,” said Skrabal. “They’re capturing all of the runoff from this very large building. It’s a great reuse, watering all these fields with rainwater.

There is more to be done. Wrightsville Beach has also overseen the installation of pervious concrete parking lots and passed strict regulations governing new construction in the town.

“If you build a house or business in Wrightsville Beach, over 500 square feet,” said Babin, “it has to have a stormwater control measure. All of the rainwater has to be contained on your property.”

The town is doing pretty much all it can to meet the goals of the multi-decade watershed restoration plan. Skrabal said. “The burden,” she said, “is on the town and us to make people understand why they have to do this. As it is, they don’t make the connection between the water on their property and the water they recreate in. People need to hear the message over and over. It’s one of the reasons we’re here.”