ATLANTIC BEACH — After listening to the public and consulting the experts, the superintendent of Cape Lookout National Seashore decided to back away from his controversial request that dredged sand be considered to shore up the eroding end of Shackleford Banks, a wild, uninhabited island that is part of the park.

“We heard from a lot of people and we consulted with a number of scientists,” Patrick Kenney said yesterday. “After weighing all that, I decided that it was in the best interest of the park that we not accept sand for the next 20 years. It wasn’t an easy decision.”

Supporter Spotlight

Pat Kenney |

Kenney, in a letter to the Army Corps of Engineers on June 11, asks that the Corps remove Shackleford Banks from its draft 20-year dredging plan for the harbor at Morehead City, Beaufort Inlet and the channel that connects the two. The Corps, which has been dredging those places for more than a century, had proposed for the first time, putting some of the dredged sand on Shackleford.

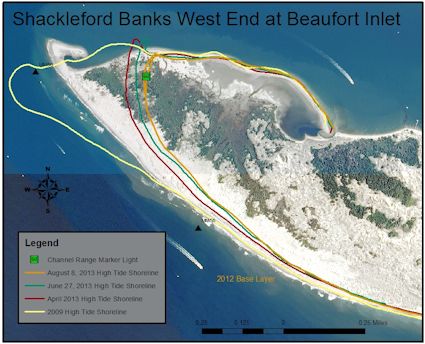

Kenney had requested that the island be considered in the plan because of the increased erosion at its western tip, which abuts Beaufort Inlet. The erosion rate there in recent years has exceeded 100 feet a year, according to Carteret County surveys. Marine navigation lights that a few years ago were in the dunes are now at the water’s edge.

The proposal touched off jitters across the inlet in Atlantic Beach, which has come to depend on the Corps’ dredged sand to re-nourish its beaches. If some of that sand started going to Shackleford, the town and county would have to cough up millions of dollars to make up the difference. They now pay next to nothing for the sand.

Atlantic Beach’s mayor, Trace Cooper, was breathing a little easier yesterday. “Maintaining deep water at the Morehead City Harbor is important to our local and state economy,” he said. “At the same time, our beaches are the backbone of our tourism industry. Diverting much needed sand from Bogue Banks to Shackleford would have been a lose-lose outcome.”

The proposal also raised sand with beachcombers and bird watchers, campers and fishermen, boaters and sunbathers and anyone else who appreciates Shackleford’s wildness. They packed the auditorium at the Duke Marine Lab near Beaufort in January for a public hearing on the draft dredging plan. Dozens of people spoke against the proposal. No one spoke in favor of it.

Supporter Spotlight

Kenney got the message.

He also consulted respected geologists like Stan Riggs of East Carolina University and Orrin Pilkey of Duke University. Kenney heard their message as well. “They had some pretty strong opinions about this,” he said. “One of the things that stuck me after talking with them was that the amount of sand we were going to get wasn’t really going to benefit the island. You had to weigh that against the adverse social and environmental effects.”

Neither were the scientists convinced that the long-term dredging of the inlet triggered the increased erosion on Shackleford. That was the justification Kenney used for asking to be included in the Corps’ plan. Park Service policy generally lets nature have its way, but it does allow superintendents to step in to salve man-made wounds.

The survey of the west end of Shackleford Banks shows the location of the shoreline at high tide in 2009 (yellow line), in April 2013 (red), in June 2013 (green) and in August 2013 (orange). The green square is the location of the range marker light. Source: NPS |

In his letter to the Corps, Kenney said the shoreline surveys and other data were too limited in time and scope to accurately determine how much of the erosion on Shackleford was caused by dredging.

While it no longer supports placing sand directly on the beach at Shackleford, the park wouldn’t object if the Corps put some just offshore where waves, wind and current would theoretically push it to the beach, Kenney said. To do any good, though, the sand would have to be dumped close to shore in less than 24 feet of water.

“That seems to be the rub,” Kenney said. “The dredges that the contractors use won’t let them put it that close to shore.”

Putting sand off Fort Macon at the end of Atlantic Beach – called a “near-shore berm” in the dredging business – didn’t replenish the town’s beaches, noted Greg “Rudi” Rudolph, the Shore Protection manager for Carteret County. “It’s been proven that it doesn’t re-incorporate into the system,” he said. “It will just remain out there, though the Corps will say otherwise. For the same reason, we’re not happy with a near-shore berm off Shackleford.”

Any sand placed off Shackleford is sand that won’t be directed towards Atlantic Beach, noted Rudolph. “If the Corps is going to put sand anywhere offshore Shackleford Banks and not on Bogue Banks, that’s completely unacceptable. Obviously, the short-term win is no sand on Shack. In the long term, there is still work that needs to be done.”

Kenney noted that that the public review process did as intended. “That’s an important point to make,” he said. “It was a planning process to look at alternatives. We looked at them and after talking to experts we came to a different conclusion. The process worked.”

Rudolph agreed. “I’m as guilty as anyone else in declaring the ink is dry when we see the word ‘draft’ on a federal government proposal, and it’s refreshing to know the process can work – it may be messy and frustrating, but it can work,” he said.