Old-Fashioned Mullet Barbecue

This dish must be prepared outside over an open fire. Using charcoal, build a fire on the ground. Allow the coals to die down. Meanwhile, salt and pepper mullets. Beginning at the mouth, insert a sharp stick or stake (about 2 1/2 feet long) lengthwise through each mullet, leaving the fish at the end of the stick. Insert the bare end of the stick in the ground at a diagonal so that the fish extends over the hot coals. Supporter SpotlightBarbecue 20 to 25 minutes. Source: Vera Gallop of Harbinger, contributed this recipe to Coastal Carolina Cooking by Nancy Davis and Kathy Hart (1986, University of North Carolina Press).

Charcoal Mullet Beresoff

Optional seasonings: 1/4 cup Carolina Treet Cooking Barbecue Sauce, 1/2 cup bottled Italian dressing or a seasoning blend of garlic powder, paprika, Texas Pete and butter to taste Supporter SpotlightPrepare a medium-hot charcoal fire in a grill or set a gas grill on medium-high or high. Rinse filets, pat dry and season with salt and pepper. Then:

Place plain or seasoned filets in a single layer on the grill grate and close the grill’s lid. Cook fish 8 to 10 minutes, depending on the thickness of the filets. The flesh will flake easily and release from the skin when the fish is cooked. Slide a spatula between the grill and the fish, lifting skin and all onto a serving plate. Serves 3 to 4. Source: Dave Beresoff |

This is part a monthly series about the food of the N.C. coast. Our Coast’s Food is about the culinary traditions and history of N.C. coast. The series covers the history of the region’s food, profiles the people who grow it and cook it, offers cooking tips — how hot should the oil be to fry fish? — and passes along some of our favorite recipes. Send along any ideas for stories you would like us to do or regional recipes you’d like to share. If there’s a story behind the recipe, we’d love to hear it.

Fall’s first chilly nips trigger a smoky scent along North Carolina’s coastal back roads. The aroma rises from home fires, but not ones to keep warm. Embers coax the savory smell of an old-fashioned dish locals lovingly call “charcoal mullet.”

Anglers may consider striped mullets bait fish. Cooks pass them up for fancier fins, but many years before fried flounder and seared grouper become seafood-menu darlings, mullets cooked over a fire were the hot tickets.

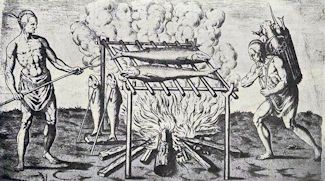

Native Americans were roasting mullets when Sir Walter Raleigh’s 1584 reconnaissance party landed on Roanoke Island.

Connie Mason |

Mullets were so popular and so abundant along the state’s shore in the 1800s that the 96-mile-long Atlantic and North Carolina railroad between Morehead City and Goldsboro was nicknamed the Mullet Line because it carried so many of the fish.

Back then, when striped mullets began their cool-weather-triggered movements known as “mullet blows,” inland farmers turned into part-time commercial fishermen, according to a report from N.C. Sea Grant. They knew autumn cold fronts combined with chilly northeast winds prompted massive mullet migrations southward. The men arranged seaside camps, where they stayed until they had netted thousands of fish during the two-to-three-month season.

Many mullets were salted, packed in barrels and transported out of state. Tiny Portsmouth Island, on the Outer Banks’ southern tip, was noted for particularly fine salted mullets. The fish’s roe, liver and gizzards were prized, especially by fishing families, who sustained life on spots and striped mullets, N.C. maritime heritage tourism officer Connie Mason, of Morehead City, said.

“Before Charlie The Tuna became the chicken of the sea, the mullet was the chicken of the sea,” she said.

Diners started bypassing striped mullets when new-fangled refrigeration systems allowed transport and storage of myriad fish. Over time, striped mullet, with its signature layer of white fat, visible on filets behind the pectoral fin, garnered a reputation for being too oily, too pungent and too humble for America’s newly refined seafood palate.

Today, striped mullet is favored bait for the more popular flounder, red drum and sea trout that mullets lay beside in seafood market coolers. When Brunswick County friends first asked Dave Beresoff, a commercial fisherman from New York, if he wanted to join them for a mullet barbecue, he replied, “Why would I want to eat bait fish?”

Native coastal Carolinians, however, still love striped mullets, preferring them stewed, pan-fried and, especially, cooked over hot coals. They even made a believer out of Beresoff, who came up with his own recipes for grilled mullet.

“Charcoal mullet is a thing of great pride” among coastal North Carolina cooks, Mason said.

To prepare charcoal mullet, the fish should be boned but not scaled, Mason explained. Lightly season filets with salt and pepper and then grill them scale-side-down just long enough to cook but not dry out the flesh, she instructed. The skin and scales act as a pan in which the filet cooks, and, later, as a container from which to fork up the delicious meat before the charred skin is discarded.

Much of charcoal mullet’s rich flavor comes from that white fat layer. Locals chastise the fish monger who tries to trim the fat, which keeps the mullet’s flesh juicy during grilling and seasons the fish as the melting fat drips onto the hot coals, producing a mouth-watering smoke.

Grilling mullet has long been a tradition in coastal North Carolina as this 1701 drawing by British explorer John Lawson attests. Drawing: UNC |

With research showing fish oil’s many health benefits, the fat may be more palatable to diners who previously snubbed mullet. Four ounces of striped mullet contain 534 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, according to the web site Self Nutrition Data. Besides heart-health claims, omega-3s are said to lower triglycerides, reduce blood pressure, improve mood and aid joint health.

Some North Carolinians skewer whole, gutted mullets lengthwise on long sticks, even rebar, then insert the skewers’ bare ends into the ground, teepee style, around a fire so that the fish extend over the hot coals.

However striped mullets are “charcoaled,” the result is a juicy, meaty, firm-fleshed filet, Mason said.

“Flounder really only takes on the flavor of whatever you cook it with; mullet stands on its own,” she said. “It has a flavor, a wonderful nutty flavor.”

As Brunswick County resident Sandra Robinson said when she grabbed a fork and dug into striped mullet from the grill at her local fish market: “Flounder cannot hold a candle to that!”