Hydrilla covers portions of Kerr Lake on the N.C-Va. border. Photo: Kerr Lake Guide. |

EDENTON — More than 30 years ago, a little green plant originally from Korea showed up in the lakes in Umstead State Park in Raleigh. Within about 10 years, hydrilla was choking Lake Gaston, impeding boat traffic and taking over the aquatic environment.

It is now plaguing canals and waterfronts in Edenton. It is in the Roanoke River and the Chowan River. It has been spotted in the Pasquotank River and on some shorelines along the Albemarle Sound.

Supporter Spotlight

Biologists fear that pristine Lake Mattamuskeet and Lake Phelps could be next.

Often called the perfect aquatic weed, hydrilla (Hydrilla verticillata) is hardy and prolific. A tiny piece of plant can imbed itself on a shoreline one season, and be clogging the waterway from bottom to top by the next year, and it very hard to kill.

“Hydrilla is like the kudzu of the water,” said Rob Emens, manager of the aquatic weed program for the N.C. Division of Water Resources.

Aptly pegged the “vine that ate the South,” kudzu, a leafy weed, has literally covered entire buildings and trees throughout the region.

Emens said that eradicating the invasive aquatic weed takes about eight years of regular treatment with an herbicide, and it is expensive. For example, he said that treatment in Lake Waccamaw in Columbus County, where hydrilla has recently been found, will cost $450,000 a year.

Supporter Spotlight

Bill Dunn, a property owner in the Arrowhead subdivision outside Edenton, said his community is struggling to fund continued treatment of their 20-acre creek off the Chowan River. The county provided some funds last year, he said, but most of the cost was borne by the community.

|

“I’ve been fighting this thing for three years, and it’s hard for citizens to come up with the money,” he said.

Dunn said that hydrilla washed over from Mill Creek Pond into coves off the Chowan River during Hurricane Isabel in 2003, and many property owners along the creeks believe the state or the Army Corps of Engineers should bear the cost for treatment.

“If it’s not done in time,” he said, “the Chowan River will be completely non-navigable.”

The state program responds to requests for assistance from local governments. The town of Edenton, for example, has worked successfully with the state on active management plans to control hydrilla in some waterways, Emens said.

But with its $200,000 annual budget – cut 60 percent during the recession – the aquatic weed program is limited, he said. Plus, it does not address treatment of open waters.

“Unfortunately, as a responsive program,” Emens said, “we’re not doing a great job in responding to hydrilla.”

Ignoring the weed is counterproductive, since it proliferates so readily and can become impossible to control. Not only can it grow one inch per day, it has been known to spread to a density of more than 130 tons an acre. It can damage fisheries and even trap young fish and crabs. Once it becomes established, hydrilla will crowd out other aquatic vegetation and cover so much of the surface that sunlight can’t penetrate.

Not that the hydrilla would notice. It survives fine in low light, and even though it is a freshwater plant, it doesn’t mind mildly brackish water. But Dare County’s salty Pamlico Sound – thankfully for the Outer Banks- is not a good environment for the weed.

Hydrilla’s reproduction is efficient and nearly unstoppable. A stem fragment the size of a fingernail will grow like wildfire, and tubers on the creeping root-like stems imbed deep in the bed mud and survive for years. Auxiliary buds called turions, another way it reproduces, may even be able to survive herbicides as well as ingestion and regurgitation by waterfowl.

The tops of the weed, which often grow together like a mat on top of the water, die off in the winter, but the tubers remain dormant at the bottom. As soon as it warms up, the plant starts its vigorous growth, and will be at the surface again in the spring.

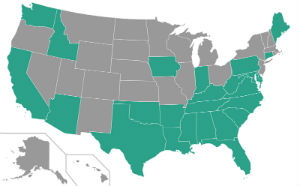

Hyrdrilla has spread to half the states, including all of the Southeast. Map: USDA |

“It’s a nasty weed,” said Steve Gabel, area agriculture and aquaculture specialist with the N.C. Cooperative Extension in Chowan County. “It’s got potential to basically clog traffic.”

Gabel said that hydrilla can be good habitat for fish until it gets out of control. He said he has seen the weed infesting not only the river creeks near Edenton, but also on the Chowan side of the Chowan River.

“There’s some potential to cause some serious problems,” he said, “and some serious economic problems.”

When Lake Gaston started managing hydrilla about 20 years ago, Emens said, the weed covered between 10 and 100 acres. The next thing they knew it was covering 3,000 acres. Then it was 20,000 acres.

“In the last 10 years, they’ve been spending $1 million a year to treat it,” he said. “They still have 3,000 acres infested with hydrilla in Lake Gaston.”

Kerr Lake State Recreation Area near Lake Gaston has also been plagued with hydrilla, and has recently started a treatment program.

“It doesn’t take a scientist to see that hydrilla is more than a menace to park experiences around infected areas at Kerr Lake,” wrote Frank Timberlake on the Kerr Lake Park Watch Web site. “Out in the water a couple of weeks ago, I walked in the mess and got tangled up. My 25-pound boat anchor weighed 100 pounds when we pulled it up covered in the choking weed.”

Hydrilla can be treated with herbicides that include fluridone, a systemic treatment that is used in large areas like Lake Gaston, and endothall, a granular or liquid that is a contact treatment. Homeowners can hire a licensed aquatic herbicide applicator to do the treatment.

Boaters and fishers are encouraged to check their propellers and gear for any sign of the weed. Photo:Skinnymoose.com |

Releasing sterile grass carp, a voracious fish that likes hydrilla, can also be effective, except in waterways where there is beneficial native submerged aquatic vegetation that the fish would also happily devour.

Dredging is avoided, since it can encourage fragmentation, one of the weed’s favorite ways to spread.

The key to management is prevention, Emens said. Right now, the monoecious biotype – which has separate male and female flowers on the same plant — is marching slowly from North Carolina to the north and west. The southeast strain is dioecious, meaning plants are either male or female, and it has already spread widely from Florida to South Carolina.

Boaters and fishers are encouraged to check their propellers and gear for any sign of the weed, and to routinely drain their bilge. Warning signs about hydrilla have been posted at public boat ramps about the need to inspect boats and their trailers and motors. Listed as a noxious weed with the state Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, it is illegal to sell or transport the plant.

“It’s very difficult to keep it from spreading within a water body,” Emens said. “What we can do is prevent it from spreading from one water body to another.”

Emens said that wildlife officials are monitoring the water in and around Pocosin Lakes National Wildlife Refuge for hydrilla.

“Those lakes are vulnerable,” he said. “They’re fresh water and they’re shallow –that’s ideal habitat. Because it’s so aggressive, if it gets into those systems, it’s likely to grow until it changes the ecology.”