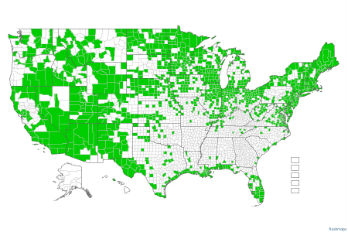

The map shows the widespread distribution of the invasive form of phragmites. Source: The University of Georgia – Center for Invasive Species and Ecosystem Health Phragmites ProfileHere’s some facts about phragmites from the Chesapeake Bay Program. Supporter SpotlightAppearance

Habitat

Range

Reproduction, Life Cycle

Other Facts

|

Driving along the winding lanes that border marshlands in eastern North Carolina, you might notice a tall, lovely grass, its feather-like tassels rustling gently as it sways in the breeze. It looks natural in its wetland setting, as if it has always been there; and in fact it has lived here for thousands of years.

Something, however, is now different.

A century ago the reed would have been part of a complex ecosystem comprised of many plant species, supporting a wide variety of animal life. Today it most likely dominates its habitat, forming a monoculture that is unnatural and uninviting for many of the animals that live in the marsh. The reed now acts as an invasive rather than a native species, destroying other natives and creating a vista that is nearly barren of other life forms.

Phragmites australis, otherwise known as common reed, is a species of wetland grass usually found in low-lying areas where there is a large amount of water in the soil and ample sunlight. It can grow from three to 13 feet high, reaching its maximum height between the ages of five and eight years. It has cane-like stems, large feathery plumes and an extensive root system of thick, white, leathery rhizomes that may be close to the surface or buried deep in the soil. Its flowers are arranged along the canes in spikelets with tufts of silky hair-like fibers. A perennial, it spreads by dispersing its seed and branching out from its horizontal underground stem, or rhizome, which can break off and re-root.

Each plant produces stands of clones which are genetically identical, noted Jack M. Whelston, a professor at Clemson University, and can exist for over a thousand years.

Supporter Spotlight

It isn’t surprising then that the common reed is one of the most widely distributed flowering plants in the world, growing naturally on most of the continents and now throughout the continental United States, barring Alaska, and in Canada. Why and how it changed its behavior in the United States from that of an uncommon native marsh resident to that of a non-native has puzzled scientists for years.

Some 50,000 species of non-native plants and animals have been documented living in the United States, some introduced on purpose, others by accident. Some, such as dandelions and Queen Anne’s-lace, often referred to as exotics, can co-exist with native species without doing any real harm. Others, labeled as invasive, can wipe out native species and destroy whole ecosystems. Examples are the Japanese vine kudzu, found in the Southeast; zebra mussels, which are devastating the Great Lakes; and Burmese pythons, now proliferating in the Everglades of Florida. Invasive species have been responsible for massive die-offs of elm, chestnut and other native trees. It is estimated that the economic cost of invasive species in this country is $120 billion a year, and phragmites is now included.

Recent research has come up with some answers to the mystery of the “uncommon” common reed in America. According to the N.C. Forest Service and a report by the state Department of Transportation, genetic testing shows that there are native and non-native families of phragmites growing in our coastal marshes. It is the non-native plants that are overtaking wetland ecosystems.

They probably arrived accidentally in the late 18th or early 19th centuries, perhaps in the ballast of ships coming from Europe. Once here, they began spreading out across the continent, displacing the native plant and other native grasses, and forming monocultures where there had been healthy ecosystems. They are presently moving into the Great Plains, where they threaten to alter important habitat for several endangered species of birds.

Through genetic research scientists have identified as many as 11 haplotypes or strains of Phragmites australis, which may help to explain the deviant behavior. The invasive, European variety is now far more common now in North Carolina than the native plants. They can be found growing in tidal and non-tidal brackish and saltwater marshes, along river edges, on the shores of lakes and ponds, in disturbed areas and pristine sites. They are especially common in roadside ditches. Described by Whelston as “ecosystem engineers,” they can alter entire aquatic ecosystems as they spread, reducing the productivity of fish, shellfish, birds and other wildlife. They do provide shade, some food and nesting sites for a limited number of species.

The European strain of these plants is grown commercially in Europe and used for thatching, livestock feed and cellulose production. Ironically, European phragmites is in decline in their original territory, causing concern because of their economic value.

It is difficult to distinguish the non-native from the native reeds without genetic testing, but generally, large stands of phragmites, such as one often sees growing along roadsides, can be assumed to be the European invasive. Phragmites may also be confused with the native giant cordgrass, spartina cynosuroides.

While it at times can be pretty, phragmites invading many of our coast’s marshes, creating a sterile monoculture. |

Eliminating or controlling non-native phragmites is now a priority with North Carolina’s wetland management organizations and many environmental groups, but the job is difficult and labor intensive. Attempts to eradicate it have included burning, cutting, draining, flooding, disking, mowing and using insects and herbicides. Some of these methods have worked in the short term, but were ineffective over the long run.

Using the herbicide Glyphosate, which is labeled for use in aquatic sites, has been found to be somewhat effective. Using herbicides in wetlands, however, presents an environmental risk, so must be done with great care. The forest service has had success treating the reeds with Glyphosate in late summer and early fall, followed by prescribed burns and successive treatments for several more years. It is imperative, the agency stresses, to follow up with monitoring to prevent the reeds from re-invading.

As always, the first step in addressing an environmental concern is identifying the problem and preventing its spreading. The invasive phragmites australis already had a head start before it was identified as what it was, but now, as scientists learn more about it and how to remove it, perhaps North Carolina’s wetlands can be spared the worst of its effects.