VANCEBORO — Discharging up to an average of 12 million gallons of freshwater a day into the swampy headwaters of Blounts Creek could bear dire consequences to aquatic life currently thriving in the brackish waters of the stream’s ecosystem.

On the flip side, the discharge could have minimal effects on the water quality, and potentially may help diversify and strengthen the natural community of fish and insects.

Supporter Spotlight

Those two divergent opinions about the impact of a proposed limestone mine in Beaufort County will come into play at a public hearing this week on a draft permit the state Division of Water Quality issued to Martin Marietta Materials. It would allow the company to discharge comingled groundwater and stormwater from its proposed Vanceboro mining operation into the creek.

The hearing will be held on Thursday at 7 p.m. at Beaufort County Community College in Washington.

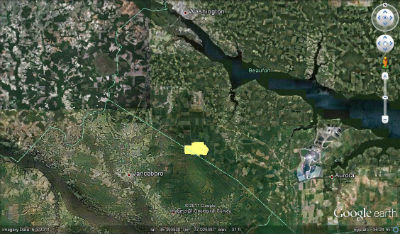

The proposed mine is northeast of Vanceboro. Photo: Pamlico-Tar River Foundation |

Pulled mostly from the Castle Hayne aquifer – the county’s water supply – the water would be discharged through two outfalls into two separate tributaries of Blount’s Creek, a popular recreational waterway known for excellent fishing. The $25 million project is designed to operate for 50 years.

Environmentalists are concerned that the aquatic nursery areas for numerous fish and submerged vegetation beds in the creek could not adapt to changes in the water chemistry – the pH and salinity levels – created by the discharge from the limestone quarry.

“The water now is very acidic,” David Emmerling, executive director of the Pamlico-Tar River Foundation, said about the creek. “It would buffer it considerably and it would become more alkaline.”

Supporter Spotlight

Emmerling said that discharges from such mines typically ebb and flow.

“Right now in the permit there’s no cap,” he said “So this could go to relatively dry to a torrent in a relatively short period of time.”

When the water volume is high, he added, it could create erosion and carry large amounts of sediment and debris that could harm the aquatic habitat. And creatures and plants that like brackish water typically do not adjust to fresh water.

“It’s sort of a migrate-or-die situation,” Emmerling said, “and if you can get far away from it to a better environment.”

But the state is comfortable that the proposed discharge complies with surface water quality standards, said Tom Belnick, the division’s supervisor of NPDES permitting unit.

“We don’t anticipate much change to downstream salinity,” he said, adding that it is projected to be less than 1 part per thousand for 10 million gallons, well within acceptable levels.

David Emmerling |

Belnick agreed that the volume of freshwater discharge would change the pH levels in the upper creek swamplands, which he described as a ditched area with little water flow, but the impact would not be apparent downstream.

Tests done by the division to project the effects on invertebrate life in the swamp, he said, reveal that the chemical change of the water would result in different species.

“Our biology person thinks you may actually get a more diverse population of insects,” Belnick said.

Martin Marietta, which received a state mining permit in 2010, has told the division, he said, that the discharge is expected to flow at a fairly constant rate that will increase over time, but not spike.

“It sounds to me like it will be a steady flow,” Belnick said. “Their projections are it will take a decade before they reach full flow.”

Belnick said that the state conducted its own studies and also reviewed studies done by the applicant’s consultants.

But Emmerling said that at least one of Martin Marietta’s studies relied on inadequate sampling and was done at the wrong time of the year.

The foundation contends that the company is obligated under law to use the least environmentally damaging alternative and that it would be a violation of water quality regulations to allow a discharge that would alter aquatic species.

“There’s so many other alternatives that they have,” Emmerling said. For instance, they could return the water to the aquifer and/or use it in municipal water systems, options favored by the foundation.

But Belnick said as part of the permitting process, the mining company had to look at non-discharge alternatives. Costs over a 20-year period to discharge into the creek, he said, were estimated at $2.9 million; to discharge with a land application like spraying, $23 million; and to discharge some water in the creek and transport some to Vanceboro’s municipal system, $6.7 million.

“By far, the most economical alternative,” Belnick said, “was direct discharge.”

The hearing will also consider issues with a second required permit, a 401 water quality certification for effects to streams and wetlands.

Public comments on both permits will be accepted through April 12. The division has 90 days after the comment period is closed to take action.