Robby Midgett and his son, Daniel, worry about their future as commercial shrimpers. Photo: Ladd Bayliss. |

STUMPY POINT — The rumble of the Rattlesnake’s engine vibrates my body down to my boots that are not yet dirty with the day’s work. I am in the pilothouse with Robby Midgett and his son, Daniel, and we are churning through the tannic waters surrounding the small village of Stumpy Point, getting ever closer to the start of the day’s shrimping.

“I’m a ninth generation Stumpy Pointer,” said Robby, between the hydraulic swishes of his wheel that guided us through the pre-dawn dark, “and Daniel’s the tenth.”

Supporter Spotlight

The sky hangs above us, embracing the remains of the weekend’s meteor shower that still sporadically illuminate the slowly brightening darkness. Other shrimp trawlers cruise beside us.

Robby lets up on the throttle. The fishing is about to begin.

With only a nod passed between father and son, the Midgetts launch seamlessly into action, easing buoys, nets and massive “pine doors” into the sluggish brown water. On this morning, Robby deploys an “otter trawl” in hopes of it returning to his boat filled with late summer brown shrimp.

Just as the sun is creeping towards the tree line above northwestern Pamlico Sound, the Rattlesnake and her Stumpy Point Bay fleet have settled to trawling speed.

Shad and Stumpy Point

The Midgetts cull through the net. The unintended “by-catch” is a source of controversy. Photo: Ladd Bayliss. |

As the southernmost village on Dare County’s mainland, Stumpy Point still exists as one of the quintessential fishing communities of our coast. Although paling in comparison to its early days as a trendsetter in the ways of gleaning profit from fisheries, the native families of the village continue to keep the fishing industry alive despite the pressures of pollution, fishing regulations and seafood imports.

Supporter Spotlight

For the Midgett family that has sustained itself primarily from the waters adjacent to Stumpy Point Bay, the story begins in the late 1800s with a young and bold Hyde County woman.

“My great grandmother, Lucy Best came here when she was 15, walked off to the post office and got married,” Midgett said proudly as a smile broke across his face. “If she hadn’t done that, my people wouldn’t be here.”

By the early 1900’, Lucy Best became a Stumpy Point resident and began a family.

Commercial fishing was by then the bedrock industry of the extremely isolated Stumpy Point. More people fished then farmed, and shad was their cash crop. Large schools of American shad moved up Albemarle, Croatan and Pamlico sounds on annual spring migrations. They supplemented the community’s diet and generated profit for those who followed them.

Dependence on the shad fishery dissipated by the late 1950s, but Midgett still remembers the bustling lifestyle that was the Stumpy Point fishing industry. Gazing across the small harbor one afternoon while heading, selling and packing shrimp, Midgett reflected on the burgeoning industry he witnessed as a child.

“Even when I was a little boy, I watched them pack out of that fish house 24 hours a day,” he said, pointing to a sagging building along the canal’s edge. “This was the shad capital of the world – there used to be 500 people living here, now we’re down to 150.”

Shad was not the target fishery during Midgett’s childhood in the late 1960s and early ‘70s. Crab and shrimp supported Stumpy Point by then. Midget began his life as a commercial fisherman going after them.

The Penaeids

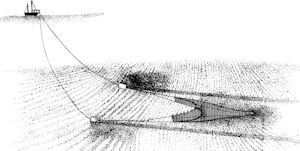

The illustration shows how an otter trawl works. |

Robby Midgett works the winch to bring up the net. Photo: Ladd Bayliss. |

Along our coast, man’s pursuit of shrimp is no short-lived affair. Native Americans and early European settlers along the coast harvested shrimp by using dip and seine nets, according to researcher John Maiolo. By the late 19th century fishermen near Wilmington began harvesting shrimp commercially, and other followed.

In North Carolina, commercial shrimpers focus on three types of shrimp from the Penaieid family: brown; white, locally known as greentails; and pink, or spotted, shrimp. Trumped only by the blue crab, shrimp are the second-most economically important fishery in North Carolina. According to N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries, shrimp harvest in 2011 produced $11 million in revenues.

The shrimp of our waters generally have a lifespan of one and a half to two years, and depend heavily on the marshes and nursery areas of local estuaries. Adults spawn in the Atlantic during most months of the year, leaving larvae to the devices of wind and currents for a safe delivery to the sounds where they begin to grow. Once these juveniles leave the safety of nursery creeks and canals, their movement back towards the oceans is often thwarted by the demand for local, fresh shrimp.

“Like most of these other boys, we usually start shrimpin’ for browns in the late summer, and move to greentailin’ in the fall,” said Midgett. “This year has been tough for the greentails, since we’ve had all this rain.”

Typically, years with high rainfall amounts force shrimp from their nursery areas quicker, said Daniel, and make them more susceptible to predation.

While most consumers don’t know the difference between a brown, greentail or spotted shrimp, the Midgetts know their habits and use different types of nets to best exploit those habits.

While an otter trawl is the net of choice for browns, a “mongoose” or tongue net is more appropriate for greentails. Often touted as one of the greatest developments in fishing technology, the otter trawl is attached to the Rattlesnake by cables that extend to the “doors,” which function to keep the mouth of the net open. A slight modification of the otter trawl, the mongoose net tows much higher in the water column, which tailors to the active greentails and their tendency to spend less time on the bottom.

Notice the green-tipped tails of white shrimp. Photo: Ladd Bayliss. |

“There’s one!” exclaimed Midgett, as we lumbered southward from Stumpy Point Bay.

It is now mid-September; the wind was whipping from the north, the chop set in for the day, and the greentails were jumping in reaction to the top buoy of the net skimming the water. Even amidst the murky chop that trailed the Rattlesnake, the jump of the greentails equaled the excitement of seeing flying fish lurching from clear, blue Gulf Stream water.

The steel cable popped and crackled under the strain of retrieving the net from the bottom of the Pamlico. The Midgetts worked the wenches to guide the line evenly on the reel. Once the net was retrieved, father and son focused on emptying the tail bag that swung slowly in the chilled air above the deck, full of the trawl’s catch, and ready to be culled.

Shrimping Struggles

The conflicts surrounding shrimping are equal to its status as the most popular seafood product in the Southeast. The types of nets used to catch fish aren’t very selective. Other animals get caught in them and often die. They are called “by-catch,” and they are very controversial among many interest groups.

To reduce by-catch, shrimpers today are required to install two different types of excluder devices for sea turtles and finfish. And, according to data from a 1999 N.C. Sea Grant Fisheries Research Grant study, the installation of these devices has greatly reduced fish and turtle mortality.

While many private groups contend that the by-catch produced by shrimp trawls is unparalleled, Trish Murphey, a biologist with N.C. Division of Marine Fisheries, said that the division’s management strategies created in 2006 are working.

“We’ve adjusted the management activities for specific areas, and we realize that by-catch is a significant issue, but our stocks are still considered viable,” she said

Robby Midgett at the helm of the Rattlesnake. Photo: Ladd Bayliss. |

Some people take small-scale sampling data and extrapolated the results to all state shrimping waters, said Murphey. The state’s management plan for shrimp is currently before the N.C. Marine Fisheries Commission for adoption, and some groups are recommending a ban on otter trawls in North Carolina. They cite by-catch of fish species as a main concern. The division, though, does not recommend a ban on shrimp trawls in state waters.

For Midgett, the loss of shrimping could mean the end of his career. Most commercial fishermen along the coast depend on several types of commercial fisheries throughout the year. Like other fishermen, the Midgetts typically shrimp from late summer to early fall. They fish for blue crabs in Pamlico Sound and fish offshore at other times of the year.

“How many fish do you think outswam my net this morning?” Midgett asked, throwing a hand back towards his bright green otter trawl, swinging lazily in the air on the way back to the dock. “Really, take a look at the area I’m towing in, the time I’m towing and the number of months out of the year I’m able to shrimp.”

As many fishermen see it, they aren’t responsible for any decline in fish stocks. A combination of market and environmental conditions are doing the damage, they say.

“Fish populations aren’t declining solely because of me,” Midgett said.

And, as if those threats aren’t enough, the flood of imports to what was once a locally-dominated market poses serious threats to today’s fisherman. According to N.C. Sea Grant, 90 percent of shrimp consumed in the United States is imported, and half of those imported shrimp are raised in man-made ponds often carved out of mangrove swamps, not caught at sea.

Amid the foreign flood, many local fishermen like the Midgetts are still able to make a living by focusing their efforts in the local community. “We take about 1 percent of our shrimp to the fish house every season,” said Daniel. “The rest of it gets sold right off our boat.”

Although an anomaly, the Midgetts recognize the privilege of their product’s marketability to coastal villages near Stumpy Point.

The Future of a Struggling Industry

Robby Midgett says he feels like the last of the Mohicans. Photo: Ladd Bayliss. |

Times have changed since Midgett was young and wide-eyed, roaming the waters of Stumpy Point Bay.

“I feel like the last Mohican now,” he sighed as he gazed over the mottled, yet well-kept deck of his boat. “I guess there are a couple of young guys continuing on… but I worry about Daniel.”

Daniel was able to experience fishing outside of his natal Stumpy Point waters this summer, as he took a part time job to chase salmon in Bristol Bay. After six weeks harvesting in Alaska’s fertile waters, Daniel returned home to continue shrimping with his father.

Atop a fish box, Daniel brushed fish scales out of his hair and mulled over his future. “It’s a hard life, and I’ve seen so many people get worn out, but I hope this never goes away,” he said, stretching his arms towards the expanse of Pamlico Sound, “There’s just nothing like this lifestyle.”

Although the challenges faced by the Midgetts are numerous, the freedom of their profession keeps the nets in the water and the locals fed.