More people moved to North Carolina last year from different parts of the country than any other state in the nation.

North Carolina’s population grew by almost 150,000 people, trailing behind only Texas and Florida, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates released last month.

Supporter Spotlight

As political leaders grapple with the demands that growth is placing on essential services like water and sewer, public safety and education, pressure is mounting on conservation groups to acquire, conserve and preserve land.

This month, more than 2,000 acres in coastal counties have been secured for permanent protection from development.

These newly protected areas are filled with natural landscape features that reduce flood risk, improve water quality, and provide habitat for plants and animals that are increasingly getting squeezed out by encroaching development.

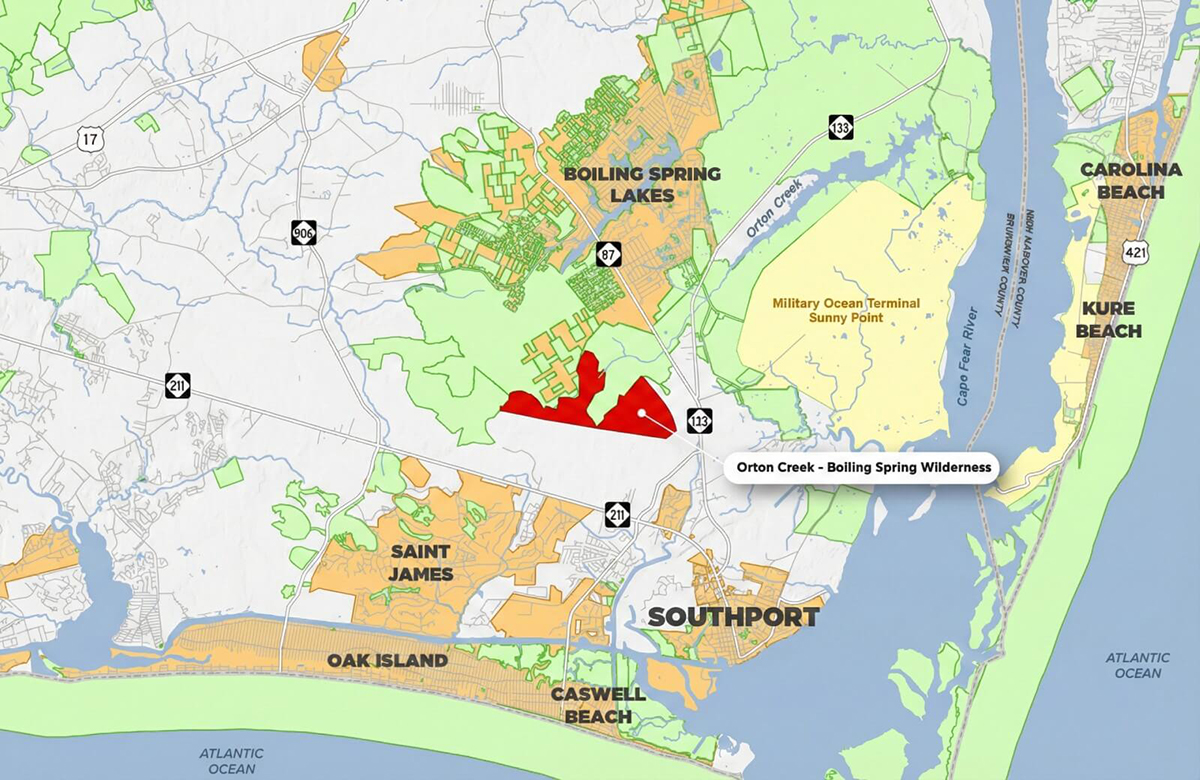

In Brunswick County, one of the fastest growing in the state, North Carolina-based conservation nonprofit Unique Places to Save acquired land that serves as a corridor between two protected natural areas, bridging what amounts to nearly 10,000 acres of conserved landscape.

“We really want to be able to maintain large, connected natural areas for habitat for species and to maintain biodiversity of our natural areas,” Unique Places to Save Executive Director Christine Pickens told Coastal Review in a recent telephone interview. “And, particularly, in the southeast of North Carolina, we have some really cool endemic species and really wonderful habitats that you don’t find anywhere else.”

Supporter Spotlight

Within the 1,040-acre tract nestled between the towns of St. James and Boiling Spring Lakes are forested wetlands, Carolina bays, sandy pine and wet sandy pine savanna.

The tract, referred to as Boiling Springs Wilderness, specifically connects thousands of acres of owned and managed by The Nature Conservancy at Orton Plantation with the North Carolina Boiling Spring Lakes Plant Conservation Preserve.

“When you connect these large areas, you’re connecting a mosaic across the landscape and there’s tiny variations of habitat availability,” Pickens explained. “What that does is allow species that use that area for habitat or refuge or migration to use those slight variations of habitat. When we experience extremes in weather, precipitation or drought or big storms, having just a little bit of wiggle room in terms of available habitat goes a long way to allowing species to be resilient to some of these extremes and some of these changes.”

Habitat that is free from being sliced up by ditches or roads is valuable to species that rely on that habitat, she said.

Take the red cockaded woodpecker, for example. These birds, which were reclassified in late 2024 from endangered to threatened, live in groups, or clusters, helping each other raise their young.

They depend on large, connected natural areas – typically anywhere from 125 to 200 acres – where living pine trees, preferably mature, longleaf pine forests, grow.

Boiling Springs Wilderness includes varying types of soils that support different sets of plants, trees, shrubs and forbs, more commonly referred to as herbs.

A good deal of pond pine and a “little bit” of young longleaf pine grace its landscape, Pickens said.

The headwaters of Orton Creek are within the project area, as are wetlands that blanket the Castle Hayne aquifer, a drinking water source for thousands of Brunswick County residents and tens of thousands in other coastal North Carolina areas.

“That’s a long-term way to protect water quality,” Pickens said. “The areas around streams act as buffers to absorb nutrients, runoff, excess components in surface water that soak in, and they get absorbed by the plants and the roots and the soils around streams. That prevents excess nutrients getting into waterways.”

Then there are the wetlands, which function like nature’s sponges, absorbing stormwater that might otherwise flood developed properties.

“Every chance we get to conserve wetlands is really important right now,” Pickens said.

That’s because state lawmakers decided to align North Carolina’s definition of wetlands with that of the federal government, which is in the process of changing the interpretation of waters of the United States that may omit protections for millions of acres of wetlands in the state.

“It may result in more wetlands being nonjurisdictional, therefore a lot more likely to be converted to uplands through ditching and draining. These conservation easements are perpetual. Once we protect it, that’s it,” Pickens said.

The Boiling Springs Wilderness project was funded through a $3.68 million North Carolina Land and Water Fund grant.

Unique Places to Save will own and manage the tract, while the state will hold the conservation easement. The Coastal Land Trust will steward that easement.

Last year, Unique Places to Save applied for another state Land and Water Fund grant to protect about 500 acres of predominately wetlands between the town of St. James and N.C. Highway 211.

“We’ve got a provisional award from the Land and Water Fund so if they have enough funding we may get funded this year for that effort,” Pickens said.

She touted efforts among other groups that work to conserve land throughout the state, including the North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review, The Nature Conservancy, North Carolina Plant Conservation Program, North Carolina Coastal Land Trust, and Cape Fear Arch to name a few.

Tyrrell County parcel transferred

Last week, national nonprofit The Conservation Fund finalized the transfer of ownership of about 1,550 acres of coastal wetlands and forestland in Tyrrell County to the Coastal Federation.

“This partnership reflects years of careful conservation planning and cooperation,” Coastal Federation Executive Director Braxton Davis stated in a release. “This acquisition protects important coastal wetlands that help filter water, support fish and wildlife habitat, and provide natural flood buffering in on the of the state’s most ecologically significant regions.”

Portions of the Tyrrell County property, which is valued at an estimated $1.7 million, are in the Land and Water Fund’s Stewardship Program, one designed to establish, monitor and enforce perpetual conservation agreements.

The property will be included as part of the Coastal Federation’s Land for a Healthy Coast program, which focuses on protecting estuaries, reducing polluted runoff, buffering floods, and boosting long-term coastal resilience.

“Some lands are simply too important to risk losing,” Coastal Federation founder and senior adviser Todd Miller said in the release. “When a property protects water quality, supports fisheries, and strengthens the natural defenses of the coast, we believe it’s our responsibility to step forward and ensure it is permanently conserved and well managed.”