Note: This story has been updated to correct the misspelling of Louis Bacon’s first name.

Restoring land as close to how it was more than two centuries ago is by no means a cheap venture.

Supporter Spotlight

Just ask Louis Moore Bacon.

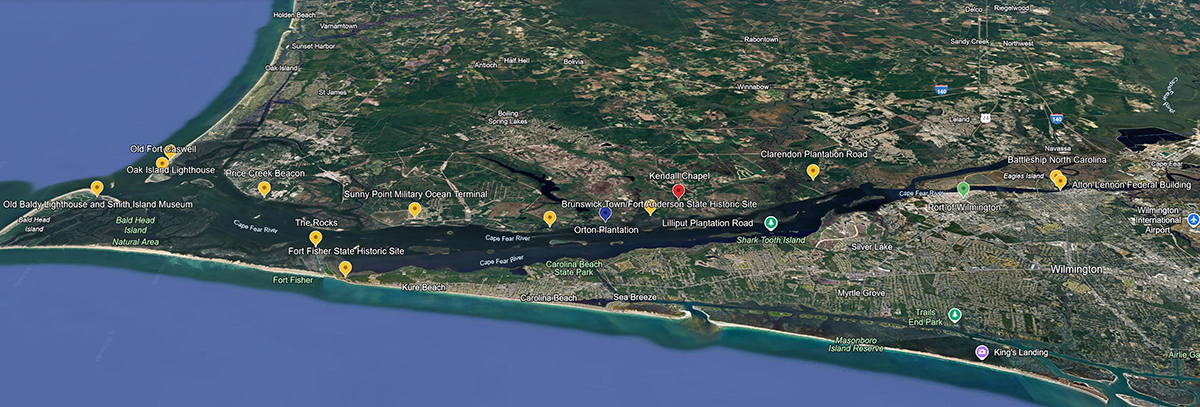

Since 2012, Bacon has invested more than $100 million in the property on which his ancestor, Roger Moore, founded Orton Plantation in 1725 off the lower Cape Fear River’s western bank in Brunswick County.

Nearly a third of that cost has gone toward restoring an expansive, historic rice field system and an earthen dike enslaved Africans built some 250 years ago to protect the fields they planted, grew, and harvested Carolina Gold rice from the river.

If the state green lights a proposed project to deepen and widen portions of the shipping channel from the Atlantic Ocean to the Port of Wilmington, all of it – the dike, 350 acres of historic rice fields and hundreds of acres of freshwater wetlands – will face threat of “irreversible damage,” according to Bacon.

In a 22-page letter he submitted to the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Coastal Management late last year, Bacon detailed how the proposed Wilmington Harbor 403 navigation project “threatens the failure” of the earthen dike.

Supporter Spotlight

“The structural integrity of the dike is Orton’s number one concern,” Bacon wrote. “The Project poses a real and unacceptable risk of catastrophic failure of the dike system. Failure of the dike will result in a cascading series of events including saltwater intrusion into the historic rice fields, rendering them incapable of growing rice and destroying the freshwater ecological water system at the Orton Property. Failure of the dike would flood the rice fields and freshwater ponds with saltwater, erasing what stands today as a preserved monument to enslaved African Americans dating back centuries.”

He closed the Nov. 24, 2025, letter with an ardent request of the division: Object to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ determination that the proposed project aligns with the state’s coastal policies and rules.

The Corps, Bacon wrote, failed to analyze how the proposed project to deepen and widen the harbor channel might affect historic and cultural resources along the river.

His objections echo those of other individuals and groups voicing concerns about how the project the N.C. State Ports Authority says is needed to keep the Wilmington Port competitive might impact those sites along the river.

Deepening the river channel from 42 feet to 47 feet and widening it along areas throughout the river will allow larger vessels to travel to and from the port, attracting more business, according to the authority.

But opponents of the proposed project say that, in addition to threatening historic and cultural resources along the river, it will accelerate erosion and exacerbate flooding, destroy habitat, disperse contaminants in the riverbed’s sediment into marshes and onto public beaches, and is not economically justified.

Like Bacon, their hope is that the Division of Coastal Management rejects the Corps’ determination.

The determination

Two days before the New Year, NCDEQ announced that the Corps was giving the Division of Coastal Management more time to complete its review of the federal determination, pushing the division’s deadline from Jan. 5 to Jan. 19.

Division officials have until then to determine whether the proposed project is consistent with the state’s coastal rules, including those under the Coastal Area Management Act, or CAMA.

The division must decide whether to concur with Corps’ determination, concur with conditions, or object.

Related: Wilmington residents see no good in proposed harbor project

If the division decides the latter, that could shutter the proposed project altogether.

“An objection generally prevents the federal permit or approval from being issued unless DCM and the project proponent negotiate a resolution that would allow the project to go forward,” according to the division’s Dec. 30 release notifying the public about the extension.

The Corps “may be entitled to certain mediation/appeal privileges” with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Office for Coastal Management, which heads programs including the National Coastal Zone Management Program and Estuarine Research Reserves and works with coastal states, territories and partners to manage resources and address impacts from climate change.

The division has to render its decision months before the Corps wraps what it says will be a detailed examination to identify all historic and cultural properties within the project study area.

“To ensure historical and cultural sites are identified and evaluated properly, the Corps is executing a study specific Programmatic Agreement (PA) with the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, the General Services Administration, the North Carolina State Ports Authority, and possibly the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation,” Jed Cayton, public affairs specialist with the Corps’ Wilmington District, said in an email responding to questions.

The programmatic agreement, he wrote, is a “commonly applied strategy to protect cultural and historical resources.”

“It facilitates more informed decision-making by allowing time for additional data collection and formal coordination efforts to extend beyond the feasibility study phase,” Cayton said.

The agreement, which is currently being reviewed, must be signed before the agency finalizes project plans, which would occur some time after the Corps releases its final environmental impact statement on the proposed project.

Under a tentative timeline the Corps has shared with the public, the federal agency is expected to release the final EIS sometime this summer.

Construction on the project would not begin until 2030 and take about six years to complete, a schedule Corps officials have said is optimistic.

‘Necessary analysis’

Today, the Orton property spans about 14,000 acres. More than 830 acres of that land, including 6,800 feet of restored and repaired earthen dike and coinciding system of canals, roads, dams, and ditches, around the rice fields is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

In his letter to the division last year, Bacon argued that CAMA protects the historic resources on his land “from irreversible damage and it protects the Property’s significant ecological resources from adverse impacts.”

The draft environmental impact statement, or EIS, the Corps released last September, “does not disclose these obvious impacts,” Bacon wrote.

“There is no analysis in the Draft EIS about the effects of the Project on the Orton Property or the CAMA-protected resources at Orton. None. This analysis cannot be deferred. The Corps’ consistency determination must be supported by ‘comprehensive data and information.’”

“The Corps’ failure to undertake the necessary analysis is the simplest reason that Division should object to the consistency determination,” he continued.

His land is among nearly 30 historic sites and properties the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources’ State Historic Preservation Office lists as being within the proposed projects area of potential effects.

Last October, that office penned a letter to the Corps requesting the programmatic agreement, “so as to address effects on known and potentially National Register-eligible historic properties to be adversely affected by the proposed undertaking and the regularly scheduled maintenance dredging, spoil placement, and environmental mitigation measures following the proposed undertaking.”

While Corps studies of historic properties that may be affected by the proposed project “appear to have focused solely on the physical impacts of dredging the river-bottom, placement of dredged materials, and locations of mitigation measures, we believe from nearly two decades of observation and monitoring erosion at historic properties along the channel that we can expect other effects will result from the proposed project,” the letter states.

Dark Branch

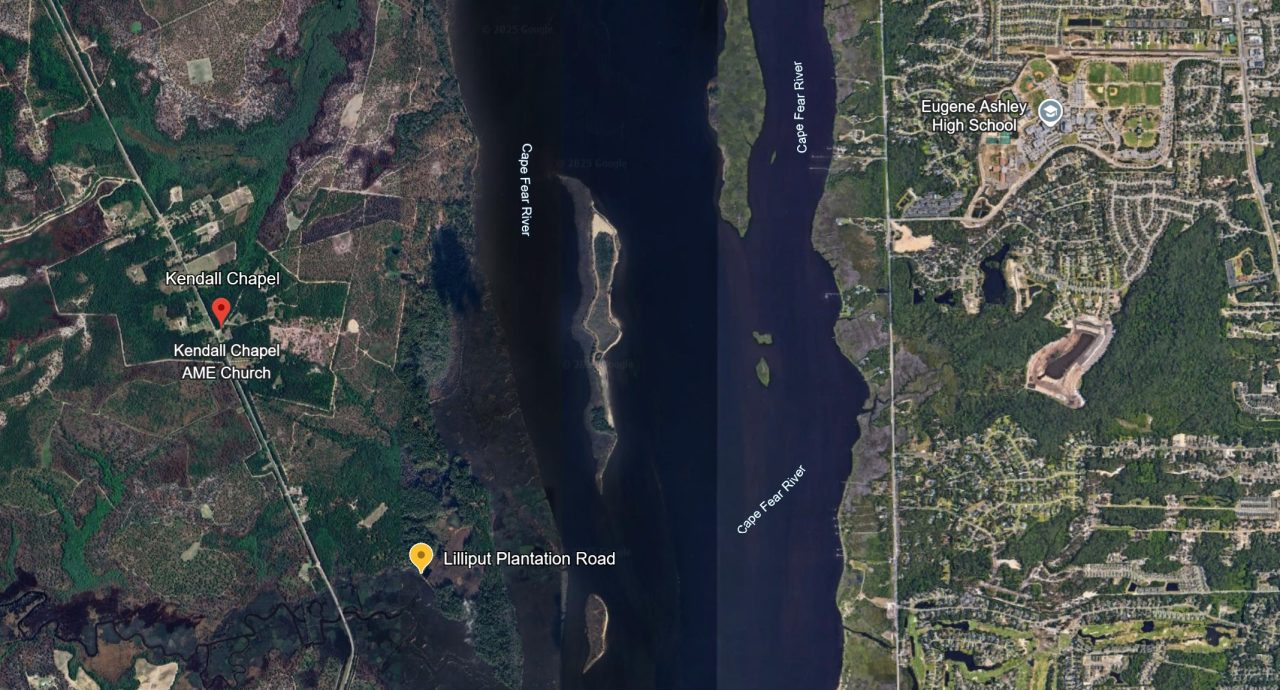

Among the list of 28 sites and properties identified in that letter is Dark Branch, a community in unincorporated Brunswick County where land remains largely owned by the descendants of emancipated slaves.

Dark Branch, also known as Kendall Chapel, was founded in the early 1870s by a handful of formerly enslaved people, including Robert “Hooper” Clark, who’d been forced to work the rice fields of Orton, Lilliput, and Kendal plantations.

The land they purchased between those plantations became “a thriving hub of Black farming, entrepreneurship, and civil rights activism,” according to the Historic Wilmington Foundation.

Dr. Charles Chavis Jr., Clark’s fourth-great-grandson and executive director of the Dark Branch Descendants Association, explained in a telephone interview that there is a direct connection between the cultural resources that have been restored at Orton and those members of the Dark Branch community have taken upon themselves to preserve.

“Everything that Mr. Moore Bacon has sought to preserve is the work of our ancestors and those who were enslaved on the various plantations,” Chavis said. “For us, this is not only about protecting our cultural resources, but also about protecting our community.”

Chavis, an assistant professor at George Mason University and founding director of the university’s John Mitchell Jr. Program for History, Justice, and Race, started the association about three years ago to preserve the community’s history.

There are about 20 historical structures in Dark Branch, including homes, a store, and sharecropping and slave cabins.

Some of those structures, as well as the community cemetery, one Chavis calls one of Dark Branch’s most sacred sites, are under threat of riverine flooding.

“We just can’t afford for it to get worse and we’re working with local organizations to try and get resources around historic resource preservation,” he said. “We’re concerned that any potential harm or more work done to the river is going to make our job as an organization harder to protect the cultural resources that we have. Based on the assessments and our conversations with those we’ve consulted with, it’s not going to get better. It’s going to get worse.”

Dark Branch is a member of the National Park Service’s Reconstruction Era National Historic Network.

According to the Division of State Historic Sites, the Dark Branch Community Historic District was added to the National Historic Preservation Study List in 2024.

Sites that make that list are good potential candidates for the National Register.

The association continues to pursue a nomination for the National Register of Historic Places.

The Dark Branch community lies within the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, which encompasses 12,000 square miles of coastal area that runs up the southern Atlantic Coast from St. John’s County, Florida, to Pender County.

The corridor links places of historic significance to the Gullah Geechee, West Africans torn from their native land and enslaved on plantations along the southern Atlantic Coast, and tells stories of their lives on the plantations and in the coastal plains after abolition.

Efforts are underway to build the North Carolina Gullah Geechee Greenway Blueway Heritage Trail that will run from Navassa to Southport.

Last summer, the North Carolina General Assembly authorized the trail’s construction.

Veronica Carter, chairwoman of the heritage trail and member of the Leland Town Council, also raised concerns about how the proposed project might affect land within the trail. Carter is also board member with the North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review.

“Deepening the Cape Fear River will negatively impact our culturally significant, state-established North Carolina Gullah Geechee Blueway portion of our trail by increasing saltwater intrusion, worsening erosion, and degrading water quality, thereby threatening sensitive habitats,” she wrote Col. Brad Morgan, the Corps’ Wilmington District commander.

The Corps acknowledges that “more surveys are needed to determine the presence of additional historic and cultural properties within the study area,” Cayton said by email. “We have already included conservative cost estimates for this work, based on known resources identified within Wilmington Harbor and experiences at other similar projects, to ensure these resources are properly managed and respected.”